Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This is the story of the modern Assyrian-Chaldean-Syriac people, and the legacy of their ancient language and faith in the pre-modern world.

Modern Assyrians celebrating ancient Akitu (New Years), al-Hasakah, Syria (2002)

The Nestorian Creed

The year is 431 A.D., and cataclysmic events are afoot in Constantinople. As the Byzantine emperor frantically prepares for a cosmic confrontation with the Sassanian Persians to the East, the Church finds itself in a threatening predicament of its own. The 3rd ecumenical council has convened for over a month now in the Aegean port of Ephesus, where 150 of the Christian World’s most prominent theologians and ecclesiastical dignitaries have been feuding over pressing issues of church and doctrine. The Archbishop of Constantinople, a man by the name of Nestorius, is the main topic of discussion here. Nestorius had daringly argued in his sermons that Christ’s human and divine natures were distinct—a doctrine known as dyophysitism, literally “two natures;” as opposed to mono- or miaphysitism, “one nature.” As a result, Nestorius declared that the Virgin Mary must be referred to by the Greek title Christokos “Christ-bearer,” in place of the suggestively monophysite Theotokos, or “God-bearer.” Perhaps all of this seems like much fuss over a technicality to the 21st century reader, but indeed these very assertions were fighting words in the early Christian world.

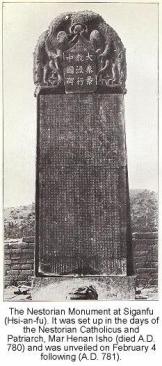

After a series of tempestuous deliberations, the synod makes its decision. Nestorius is officially condemned in five separate canons produced at the council, declared a heretic, excommunicated from Christianity, and exiled from the realm. The deposed Patriarch gathers his followers and embarks on an exodus to the East, all the time insisting his ideals were in fact “orthodox.” But Nestorius was not alone–the Council’s findings were rejected by many of the attendees from the fringes of the Byzantine Empire, including the Syriacs, the Egyptians, the Ethiopians and the Armenians, all of whom heretoforth became alienated from Western Christendom. These dramatic events in the 5th century AD amounted to the “Nestorian Schism,” which gave birth to the Persian Church (the Church of the East) and resulted in the dissemination of Nestorius’ creed from Egypt in the west to China in the east. Within a short period, the Nestorians would reach the T’ang court at Chang’an (Xi’an), and would enjoy evangelical success among Mongol tribesmen, Sogdian merchants, Chinese sailors, and South Indian farmers along the way.

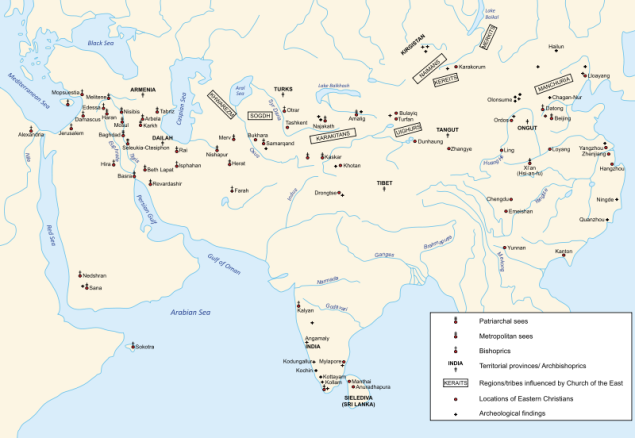

Extent of the Nestorian Church (Church of the East) based in Persia in the Middle Ages

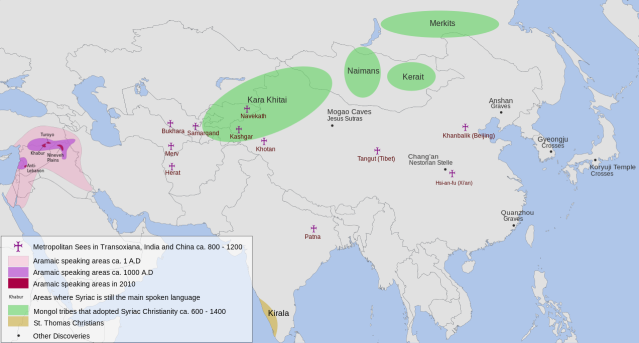

The extent of Syriac Christianity in Asia and the Aramaic language in the Near East. Green represents Mongol tribes that adopted Christianity

.

Daqin Pagoda, a 7th century Nestorian Church near Xi’an, China

St. Gregorios Malankara Syriac Orthodox Church, Kerala, India. Historically the Christians of India were affiliated with the Persian Church (the Church of the East), until local Patriarchs forged relationships with the Syriac Orthodox Church in the 19th century (which, like Nestorianism, is a Non-Chalcedonian creed).

Now let us shift our lens from Constantinople to the Persian capital of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia. Here on the Tigris, the Sassanians had established a world-class urban center comprised of a series of sprawling “settlements”–a spectacle that inspired the Arab Muslim invaders of the 7th century to call the city Al-Madā’in, or “The Cities.” But most important to our story here is the ethno-linguistic dichotomy of Sassanid Mesopotamia—namely, a Zoroastrian Iranian elite and a Christian, Jewish, and Sabian Aramaic-speaking bourgeois (there were also minorities of Greeks, Armenians, Arab Christians, etc.). In an attempt to deter the Christians of Persia from succumbing to Byzantine sympathies, the Iranian elite actively pursued a policy of aligning the Aramaic-speaking Christians of the Sassanian realm with the new heretical Nestorian creed from Byzantium. The goal was to anathematize the Persian Christian population from the Patriarch in Constantinople, and thereby prevent defection and collaboration with their coreligionists.

Ruins of Tâq-i Kasrâ Palace at the Sassanian Persian capital, Ctesiphon (located on east shore of the Tigris, Seleucia was across from it on the west shore) in modern-day Iraq

Thus under the support of Sassanian monarchs and noblemen (nakhwadârân), Nestorian refugees were welcomed from the Byzantine Empire into the Sassanid realm and were soon given authority of the Diocese of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in the capital, headed by a Catholicos later deemed the “Patriarch of the East” or the “Patriarch of Seleucia-Ctesiphon”. This was the genesis of the Persian Church, which had jurisdiction over all Nestorian Christian communities throughout the world. Of course Christian Europe would forever view the Nestorians as “false Christians”; as oriental bumpkins whose knowledge of Christ and doctrine was tantamount to paganism, and would even dispatch missionaries with the sole purpose of “converting” them to Christianity. But these ecclesiastical attitudes should not undermine our understanding of the role that Nestorianism has played in historical developments in Eurasia. For example following the conquest of Jerusalem, the Nestorian wife of Shahanshah Khosrow II, Queen Shirin, brought the holiest relic of Christendom, the Holy Cross, back to her palace in Ctesiphon. The sacred object remained at Shâhigân-i Spêd Palace until it was repatriated to the Holy Sepulchre by the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius in 628 A.D.

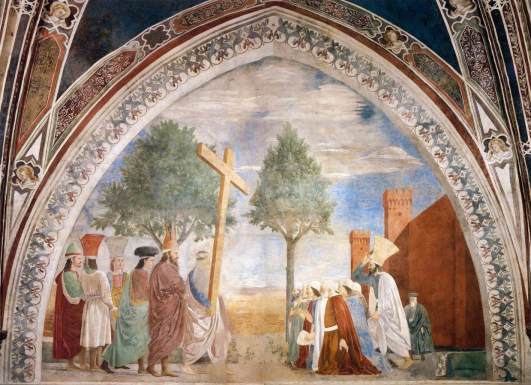

Exaltation of the Holy Cross, Piero della Francesca at Arezzo, Italy. The Byzantine Emperor Heraclius returns the relic of the True Cross to Jerusalem from Ctesiphon in 628, following its capture by the Sassanian Persian King Khosrow II and his Nestorian wife Shirin fourteen years earlier.

Aramaic Languages

But who exactly were these Aramaic-speakers, soon-to-become-Nestorians? Here we have to deal briefly with some terminology. Of course prior to the Muslim invasion of the Near East and the subsequent Arab migration into that region from the Arabian Peninsula in the 7th century AD, the Near East boasted a very different ethno-linguistic landscape from that of today. Mesopotamia and Greater Syria were primarily populated by a group of people known collectively as Aramaeans or Nabataeans (from Arabic nabaṭi, pl. anbāṭ). The Aramaeans spoke languages of the Aramaic group, which is a Semitic language family related to Hebrew, Arabic, Ugaritic, Phoenician, Akkadian, and Amharic. The ancient Neo-Assyrian empire witnessed the spread of the Old Aramaic language which eventually displaced Akkadian, and thus Aramaeans throughout history have come to refer to themselves (somewhat nostalgically) as “Assyrians” as descendents of that people. Among Aramaeans there were Jews, Sabians (Mandaeans), Samaritans, and Christians. These non-Zoroastrians were the commoners and working class of Parthian and Sassanian Mesopotamia. The Nestorian Church or Persian Church eventually developed into the “Assyrian Church of the East”, which later underwent pro-Catholic (Chaldean) and pro-Jacobite (Syriac) schisms. In sum, the terms Aramaeans, Nabataeans, Sabians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Syriacs, Mandaeans, all refer to ancient and modern speakers of Aramaic languages.

| NENA (Iraqi Koinē) | Ṭuroyo | Neo-Mandaic (Khorramshahr) | Standard Arabic | Modern Hebrew | English |

| āna ewin/ewan* | -(a)no, -(o)no* | -(a)na | ana | aní | I [am] |

| shlāma | shlōmo | shlomā | salām | shalóm | peace |

| khayūta | ħaye | heyyi | ħayāt | khayím | life |

| shimsha | shemsho | shāmesh | shams | shamásh | sun |

| malka | malko | malkā | malik | mélekh | king |

| kikhwa | kukwo | kakuā | kawkab | kokháv | star/planet |

| nāshe | nōshe | barnashānā | nās | anashím | people |

| libba | lebo | lebbā | lubb<(qalb) | lev | heart, core |

| lishāna | lishōno | leshānā | lisān | lashón | tongue/language |

| resha | risho | rishā | ra’s | rosh | head |

| khulma | ħulmo | — | ħulm | khalóm | dream |

| ida | idho | idā | yad | yad | hand |

| brōna, bnūne | abro, abne | ebra, ebri | ibn, abnā’;banūn | ben, baním | a son, sons |

| brāta, bnāte | bartho, bnōtho | berāt, benāthā | ibna;bint, banāt | bat, banót | daughter, daughters |

Language comparison table prepared by the author of modern Semitic languages showing some common cognates: Northeastern Neo-Aramaic (NENA), Ṭuroyo (Neo-Aramaic from Ṭur ‘Abdin), Neo-Mandaic, Standard Arabic, and Modern Hebrew. *NENA and Ṭuroyo distinguish between gender in the 1st person copula.

Coin (drachma) of Shapur I with Aramaic inscription, Sassanian period. Aramaic was the official administrative language of pre-Islamic Iranian dynasties, and typically numismatic inscriptions were in Aramaic. i.e Bagi Papaki Malka “Divine King Babak”; Mazdisn Bagi Artahshatr Malkan Malka Airan Minuchitri min Yazdan “The Ahura Mazda-worshipping Divine Artaxerxes, King of the Kings of Iran, heaven-descended of the Gods”.

Aramaic languages have enjoyed a great deal of political, literary, and religious patronage in the Iranian world, reaching Greece and even India. After all, Old Aramaic displaced Hebrew as the language of Israel by the 6th century BC, and was the language spoken by Jesus Christ himself. Aramaic became the lingua franca of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and “Imperial Aramaic” became the official administrative language of pre-Islamic Iranian polities through the Sassanid period. It might come as a surprise that instead of the Iranian term Shahanshah, Parthian and Sassanian coins usually feature the Aramaic calque Malkan Malka. Before the arrival of Islam and Arabic script, many Middle Iranian languages (Middle Persian, Parthian, Sogdian, Chorasmian, with the exception of Bactrian and Khotanese) and even Avestan were written in modified Aramaic scripts, and inscriptions in these language even contain Aramaic heterograms called huzwârish. What’s more, Middle Aramaic languages like Syriac, Mandaic, and Babylonian Aramaic (the language of the Talmud) became important liturgical and scholarly languages in the pre-Islamic Near East. The School of Nisibis was a 4th century Syriac-language university, and like the Academy of Gondeshapur in Persia, is sometimes referred to as the world’s first university. With the advent of Islam in the 7th century AD, the inhabitants of the Near East soon relinquished Aramaic for Arabic, except for small pockets of Christians, Jews, and Sabians who retained their language and enjoyed dhimmi status under the Caliphate.

Yasna 45.1 from the Gathas in Avestan script. Avestan is the liturgical language of Zoroastrianism; this script was developed in the 3rd or 4th century based on Aramaic script (with Greek influences).

Today, Northeastern Neo-Aramaic languages (NENA)–which are not derived from any classical literary Aramaic language but rather from a rural periphery group–are still spoken by Assyrians, Chaldeans, Syriacs, and Kurdistani Jews residing in Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, Armenia, Georgia, and abroad. The standard literary version of NENA was developed in 1836 by Justin Perkins, an American Presbyterian missionary to Iran, and is based on the Urmia dialect of Iran (Urmežnaya). However the modern spoken varieties of NENA continue to exhibit a great deal of morphological, phonetic, and lexical variability resulting in strained intelligibility among groups. This situation has been in part ameliorated by the Iraqi Koinē phenomenon, but dialects remain drastically distinct along lines of religious affiliation, region, and even village. Aside from the NENA dialect continuum, the other Neo-Aramaic languages are Ṭuroyo spoken in Ṭur ‘Abdin in southeastern Turkey (also called Central Neo-Aramaic), Neo-Mandaic spoken by Mandaeans in Iraq and Iran, and Western Neo-Aramaic, spoken in a set of three small villages in the Anti-Lebanon mountains northwest of Damascus. None of these languages are mutually intelligible.

Assyrian men in traditional garb in ‘Ankawa, Erbil, Iraq

While the impact of Iranian languages (Parthian Pahlavi, Sassanian Pahlavi, New Persian, Sorani, Kurmanji) has historically been paramount on Aramaic languages, there are at least a few examples of lexical borrowing in the opposite direction. Perhaps some of us are familiar with a few Persian words of Aramaic (Syriac) origin. For example,

1.) Sumac or Somâgh in Persian (>Arabic sumāq >Syriac summāq “red”, from root s-m-q, akin to NENA smuqa, smiqta “red” and Ṭuroyo semoqo, semaqto “red”)

2.) Yaldâ (>Syriac yaldā “birth” from the radicals y-l-d, cognate to Arabic root w-l-d via Northwest Semitic isogloss w- > y-; ArabicForm I gerund: wilāda, milād “childbirth”; Form V gerund: tawallud, “generation, engendering” → N.Persian tavallod “birth”). Thus the holiday Shab-e Yaldâ is “The Night of Birth”, celebrating the birth of the Iranian God Mithra, and the name was probably coined in the Sassanid period.

3.) Kiânâ (>Syriac kyānā “nature, Innate essence [of Christ]”, also NENA kyana, cognate to Arabic kayān “entity”, from root k-w-n). Note a false Persian etymology: “Queen”, from kiân “royal”+â (“-â” is not a Persian feminine suffix; Middle Persian had already lost grammatical gender, which only existed vestigially from Old Persian, such as in nouns of the feminine -ka declension as –əg → N.Pers –ə, which has shifted to –ê in Western Persian. i.e. O.Pers fra-zāna-ka → M.Pers Frəzânəg → N.Pers Farzânê “intelligence”; O.Pers Spaita-ka, M.Pers Spêdəg, N.Pers Sêpidê “white, clean”).

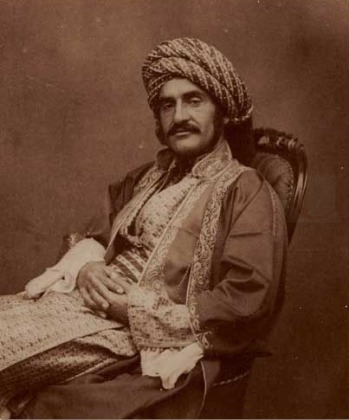

Hormuzd Rassam (1826-1910), a native Assyrian Assyriologist from Mosul who discovered the clay tablets that contained the Epic of Gilgamesh as well as the Cyrus Cylinder at the ruins of Babylon. The name “Hormuzd” was a Sassanian-era corruption of Avestan “Ahura Mazda”, a popular name among Kings, and is still used among Aramaic-speakers today.

Nestorian Christianity in East Asia

In the 12th century AD, a legend developed among European Christians about a righteous King who ruled over a true Christian nation somewhere among the pagans of the Orient. His name was Prester John, and he became the subject of ecclesiastical missions, military expeditions, and exploration by Europeans up through the 17th century. One school of speculation ascribed the identity of Prester John to the Mongolian Kereyid chief, Ong Khan. Indeed Ong Khan’s tribe, the Kereyids, had converted to Nestorian Christianity, but that did not stop Genghis Khan from marrying his son Tolui to one of Ong Khan’s nieces, Sorkhakhtani Beki. This Nestorian matriarch was mother to the four great inheritors of the Mongol realm: Kublai Khan, Hulagu Khan, Möngke Khan, and Ariq Böke. She is regarded very highly in the Secret History of the Mongols, where it is related that the Great Khan Ögedei consulted her on various matters. In 1310, she was regarded as “Empress” in a ceremony that included a Nestorian mass, and her body was enshrined in a Christian church in Ganzhou in 1335, where sacrifices were to be offered.

.

Tolui Khaqan and his queen consort, Sorkhokhtani Beki, a Mongolian Nestorian Christian and mother to the four partitioners of the Mongol Empire: Kublai Khan, Hulagu Khan, Möngke Khan, and Ariq Böke.

Sorkhakhtani’s son Hulagu Khan, who founded the Ilkhanate in Persia, also married a Mongolian Nestorian princess by the name of Doquz Khatun. She is said to have accompanied her husband during his campaigns, and during the Siege of Baghdad in 1258, she even ordered him to spare the Christian inhabitants of that city from the bloodbath that ensued. Hulagu offered the royal palace to the Nestorian Catholicos Mar Makkikha II, and ordered a cathedral to be built for him. In this remarkable episode, the far-flung geographical extent of the Nestorian faith facilitated an unseemly alliance between peoples from Mesopotamia and Mongolia.

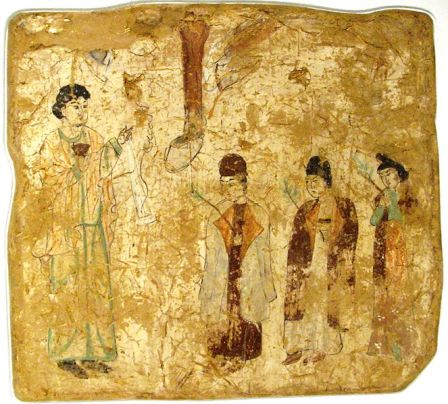

Wall painting from a Nestorian Christian Church in Qocho, China (683-770 AD)

But within centuries, Nestorianism too would succumb to the test of time. Sporadic persecution of Nestorians as well as neglect by their European coreligionists would weigh down on this already declining creed. Today Neo-Aramaic speakers are small in number, in great part due to the mass-killings of Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire and later the Assyrian Genocide committed by the Young Turks during WWI and then the Ba’athist regime in Iraq. The Assyrian Church of the East moved its Patriarchal See from Baghdad to Chicago, Illinois in 1989, where assimilation has become an imminent threat among the diaspora. But despite these calamities, the Nestorian legacy and the Aramaic language still provides us with a kaleidoscopic view of connections between peoples and cultures; as the timeless diplomats between East and West, between our past and our present. Indeed we can make use of the texts, art, and architectural ruins to put together the pieces of this undying chapter of the human story.

Contemporary Assyrian singer Juliana Jendo singing Burbaslan Go Mdinate “We have dried up in our [own] cities”, about the dwindling Assyrian population in historic homeland, migration, assimilation abroad.

External Links:

Juliana Jendo- Lishana Aramaya “Aramaic Language”, with George Homeh

Juliana Jendo- Lele Kul Watan Yimma “No Country is our Motherland”, filmed at the Chaldean Nestorian Church in Kerala, India in 1994.

Juliana Jendo- Beth Yaldakh Hawe Brikha “Happy Birthday”, part of campaign to preserve Neo-Aramaic language among children of the diaspora in the Unites States.

Jualiana Jendo- Barboslan Go Mdinate “We have dried up in our [own] cities”, speaks about the dwindling Assyrian population in historic homeland, migration, assimilation abroad.