Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This article explores the history and etymology of the Sogdian term “Afšīn” as a derivative of Old East Iranian *xšaēwan in contrast to an untenable etymology that has been proposed from Avestan “Pisinah.”

(1) Wall painting of the goddess Nana (merged with Anāhitā in Sogdia) discovered in the palace of the Afšīns (Kala-i Kahkaha I), Bunjikat, Tajikistan, 8th-9th century CE (2) Wall painting of a deity with features reminiscent of Chinese forms, Kala-i Kahkaha I, early 9th century CE, Hermitage Museum (3) Ruins of a palace (Kala-i Kahkaha), seat of the Afšīns at Bunjkat, which served as the capital of the principality of Osrūšana from the 6th to 9th centuries CE, Sughd province, Tajikistan (4) Burnt wooden statue, Kala-i Kahkaha, Bunjkat, 6-7th century CE

Background

Afšīn was a Sogdian-language title used by the rulers of various principalities in Transoxiana (modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) in the centuries immediately preceding the advent of Islam. However, the etymology of the word remains shrouded in uncertainty. Today, Afšīn (Afshin, Afsheen, Ashfeen, Avşîn, Ōšin) is used as a boy’s name in Iran, Armenia, Iraq and Turkey and, apparently through Persian influence, as a name for both boys and girls in the Indian subcontinent. The gender shift may stem from erroneous interpretation of the second element as the Persian affix -īn, signifying likeness, which is found in multiple Persian female names adopted by Hindustani Muslims (e.g. مهين Mahīn “moonlike”; پروين Parvīn “fairylike”; شيرين Shīrīn lit. “milk-like [sweet]”, etc.). It is most similar in shape to another Hindustani female name, assimilated as Afrīn (from Persian آفرين āfarīn “creation”), which may have influenced it. A later Hindustani version, Ašfīn, resulted from metathesis of /f/ and /ʃ/, perhaps being conflated with the Rigvedic divine twin horsemen, Aśvín (अश्विन्). The Armenian variant Օշին Ōšin is explained by vocalization of the sequence /af/ resulting in the diphthong /au/ and then monophthongized to ō (e.g. earlier Աւշին Awšin; compare vocalization of Persian افرنگ afrang to اورنگ aurang “throne; splendor”, i.e. اورنگزیب Aurangzēb lit. “ornament of the throne”, royal epithet of the sixth Mughal emperor), which has also occurred in renditions of the name in other languages, like Sorani Kurdish (اوشين Awšīn).

Its modern use is probably an homage to the last of the Afšīns, a certain Khedār Kāvūs (?- 841 AD). Khedār Kāvūs was a scion of the rulers of Osrūšana, a Sogdian principality that lay at the southernmost bend of the Syr Darya and extended roughly from Samarqand to Khujand. He is popularly held to have been a [secret] protagonist of the ancient Iranic identity and imperial feeling in the face of Arab-Islamic intrusion. In the Arabic sources, Khedār Kāvūs is often referred to simply by his title, rendered al-Afšīn (الأفشين). When a power struggle and dissension broke out among the reigning family of Osrūšana, the prince al-Afšīn (Khedār Kāvūs) fled to Egypt where he succeeded in winning caliphal favor through his role as top commander of the Abbasid guard to the heir apparent, al-Mu’taṣim. After suppressing multiple rebellions and obtaining governorship of Egypt, al-Afšīn rose to the highest echelons of power and circumstance under the Caliph al-Mu’taṣim during a shining career of two decades. He was appointed supreme commander in the Abbasid campaigns against Byzantium and was rewarded governorship of Azarbāyjān, Armenia, and Sind for his victories. With al-Afšīn came a large band of his followers, fellow natives of Osrūšana, who were integrated into the army and, serving under their prince, became known as the al-Ushrūsaniyya (ٱلْأُشْرُوسَنْيَّة) regiment.

However, in later years a series of intrigues caused his star to decline. He was eventually tried in court for suspected collusion with the anti-Arab renegade prince of Ṭabarestān, Māzyār, and also on the grounds that his conversion to Islam had been in some regards insincere. The allegations he faced included (1) housing richly ornamented Buddhist, Zoroastrian or Manichaean relics (“bejeweled idols and sacred books of the Magians”) in his personal palace at Sāmarrā, which he claimed were family heirlooms (2) ordering the flogging of a muezzin and imam in Osrūšana as punishment for converting a local shrine into a mosque, and (3) remaining uncircumcised. Following his indictment, al-Afšīn was imprisoned and starved in Sāmarrā, where he perished in 841 A.D.

It has been widely disseminated that the word Afšīn represents an Arabic corruption of a Middle Persian form, Pišīn, corresponding to Avestan 𐬞𐬌𐬕𐬌𐬥𐬀𐬵 Pisinah–, of unknown etymology. A closer analysis of the available linguistic and historiographical data casts doubt on this idea, and it shall instead be argued that the title is ultimately descended from Old Iranian *xšáyati “king, ruler” via Sogdian *xšaēwan (whence also Old Persian *xšāyaθiya —> New Persian šāh).

Coin in the name of Raxanč, Afšīn (lord) of Osrūšana. Tamgha symbol on the reverse with name of the ruler in Sogdian rγʾnč MRAY “Raxānič Afšīn”. Excavated in the Palace of Kala-i Kahkaha I, Bunjikat, Tajikistan, 7th century CE

Pišīn and Afšīn as False Friends

First, the only attestation of Avestan Pisinah- is in the form Kavi (“king”) Pisinah in the Zam Yasht, or “Hymn to the Earth”, of the Younger Avestā (composed based on existing oral traditions in the early Sasanian period). Kavi Pisinah is one of the listed successors of Kavi Kavāta (كى قباد Kay Qubād), the other successor kings being Kavi Usaδan, Kavi Arṣ̌an, Kavi Byarṣ̌an, and Kavi Syāvarṣ̌an. In the later Iranian national epic, the Shāhnāmeh, Kay Qubād is fashioned as the founder of the Peshdādiān dynasty and his third son كى پشين Kay Pišīn (from Avestan Pisinah) is mentioned in passing as characters proudly attribute their descent to him who was “wise” and whose “heart was full of giving”. In a repeating formula substituting only the names of the five successors, Pisinah is mentioned as follows in the Avestā:

𐬐𐬀𐬏𐬋𐬌𐬱 𐬞𐬌𐬕𐬌𐬥𐬀𐬢𐬵𐬋 𐬀𐬴𐬀𐬊𐬥𐬋 𐬟𐬭𐬀𐬏𐬀𐬴𐬍𐬨 𐬫𐬀𐬰𐬀𐬨𐬀𐬌𐬛𐬈

kauuōiš pisinaŋhō aṣ̌aonō frauuaṣ̌īm yazamaide

We worship the fravaṣ̌i [eternal spirit] of the righteous Kavi Pisinah (Y. 13.132, 19.71)

The context in which an Indo-Iranian king’s personal name would be adopted as a regal title in Transoxiana is obscure indeed. Perhaps Avestan Pisinah represents the personification of an existing regional title rather than referencing a real individual. Although, this theory would not explain the absence of attestation to the other personal names listed in the Zam Yasht as regal titles, nor provide any hint to the ultimate etymology of Pisinah. Despite evidence pointing to Zoroastrianism’s status as the dominant religion in Transoxiana throughout the first millennium AD, it is unclear to what extent the religion was patronized by individual Sogdian rulers or the state of its health in the centuries immediately preceding the arrival of Islam. It is clear that Sogdian Zoroastrianism was different in some respects from the officialized Sasanian brand that was practiced in Western Iran. The Sogdian version appears to have featured Old Iranian cult patterns and perhaps a degree of syncretism with Indic religions. Beyond the Sogdian Zoroastrian contingent, Buddhist texts in particular form a significant portion of the surviving Sogdian language corpus, and the primary role Sogdian Buddhist monks from Ān 安 (Bukhara) and Kāng 康 (Samarkand) played in the diffusion of Buddhism into China is well-known. Manichaeism had also taken firm hold in the region since it had exploded on the scene across Eurasia and North Africa in early Sasanian times, and the conversion of the Uighur Qaghan to the universalist faith in the 8th century AD is attributed to Sogdian Manichaeans. Nestorian Christians also formed an important contingent, with thriving colonies present throughout T’ang China. The proposed link between Pisinah and Afšīn appears doubtful in light of these considerations.

Second, to the author’s knowledge there exists neither a regular correspondence between Middle Persian pi– and New Persian af- nor any instances of Middle Persian pi– yielding New Persian af- through Arabic interference. Instead, the element ab- or –af is the Middle Iranian descendent of Proto-Iranian *Hapá “away” (Avestan 𐬀𐬞𐬀 apa), and appears extensively already in Middle Persian:

Afrāštan (ʾplʾstn’): to raise, elevate (NP afrāštan or afrāxtan)

Afrōxtan (ʾplwhtn’): to kindle, to illuminate (NP afrūxtan)

Afzār (ʾp̄cʾl, ʾp̄zʾl): wear; material, instrument, tool (NP afzār)

Afzōdan (ʾpzwtn’): to increase; to add (NP afzūdan)

Afšāndan (ʾpšʾn-tn’): to scatter, disperse (NP afšāndan)

Afgandan (ʾpkntn’): to throw, to hurl (NP afkandan, afgandan)

Afrang (ʾplng): throne; splendor, majesty (NP afrang)

Other Middle Persian words with unclear etymologies but perhaps also derived from Hapá-, contained the element af-:

Afsōn: spell, incantation (NP afsūn)

Afsān: myth, story (NP afsāna)

Afsōs: scorn (NP afsūs)

Sometimes, af- appeared in New Persian by prothesis of a- to the cluster frā-:

Afrāsiāb: From Middle Persian plʾsy̲d̲ʾp̄’ (frāsiyāb), plʾsyʾk’ (frāsiyāg). Compare Avestan 𐬟𐬭𐬀𐬢𐬭𐬀𐬯𐬌𐬌𐬀𐬥 fraŋrasiian

Third and most importantly, a regal title containing the element af-, namely “Afšīyan of Samarkand” (βαγο ογλαργο υονανο þαο οαζαρκο κοþανοþαο σαμαρκανδο αϕþιιανο Lord Uglarg, the king of the Huns, the great king of the Kushans, the Afšīyan of Samarkand), is attested in the Bactrian language as early as the 5th century AD—at least three centuries before the arrival of Islam. Another kindred title, Afšūn, appears in an 8th century epistle written in Sogdian addressing the ruler of Khākhsar from the king of Panjikent, Devaštič, whilst he was hiding on Mount Mugh from his impending doom at the hands of the Arab-Muslims. These examples illustrate the futility of advancing the element af- in Afšīn as a corruption by Arabic speakers following the advent of Islam. The element af- already existed in Middle Persian and Eastern Iranian, with the titles “Afšīyan of Samarkand” and Afšūn attested in Bactrian and Sogdian, respectively. Moreover Arabic interference would not be expected to result in the proposed transformation. Therefore, in searching for the name’s origins, any involvement of Middle Persian Pišīn and Avestan pisinah– can rightfully be discarded.

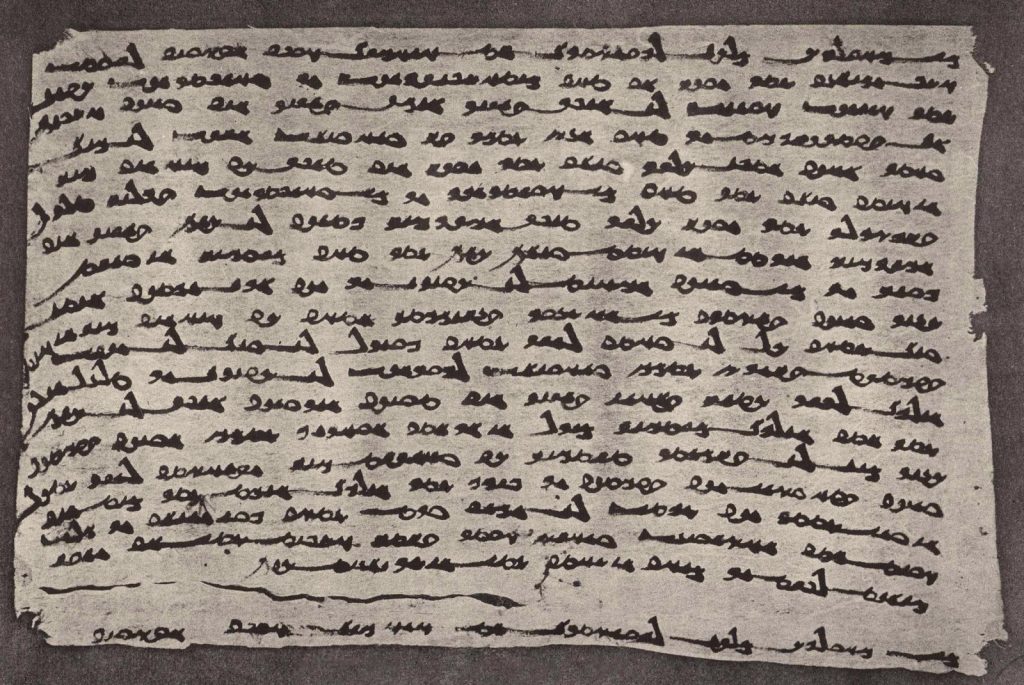

Letter written in 722 CE on pale-gray Chinese paper in Sogdian from Devaštič, ruler of Panjikent, to Afšūn, ruler of Khākhsar, discovered on Mt. Mugh, Tajikistan. Devaštič reproaches the Afšūn for his incompetence in communicating with the Turkic qaghan, but also expresses a hope that the Turks will come to his rescue on Mt. Mugh where he is making a last-stand against the invading Arab-Muslims. It does not seem that they ever did.

Sogdian Etymologies from Old Iranian

We ought to consider the attestations of Afšīn and variants thereof in the original sources. Was this a Western Iranian rendition of an Eastern term? An internal Sogdian transformation of a high frequency word? In our analysis we need make mention of another Sogdian title, Axšīd (Arabic: الإخشيد al-Ixšīd), a variant of xšyδ, xšēδ “chief; commander”, which was in use among the rulers of Farghāna and attested in the early Islamic period. It is also attested in the late 8th Middle Persian Manichaean text Mahrnāmag as the title of the ruler of nearby Kāšğar (疏勒 Shūlè), a Saka-speaking city-state in the Tarim Basin. The currency of the title must have persisted in the Farghāna valley as late as the 10th century, since the short-lived Ikhshidid dynasty of Egypt and the Levant (935-969 AD) was apparently founded by a Baghdad-born prince of Transoxianan extraction, styled as Muḥammad al-Ixšīd.

Attestations of Afšīn and renditions akin to it are summarized in the table below, followed by a discussion.

| Title | Native Locality | Attested Language | Time period |

| Axšīd or Ixšīd | Farghāna, Kāšğar | Sogdian, Arabic | 642–755 CE |

| Afšīyan | Samarkand | Bactrian | 5th century CE (Lord Uglarg) |

| Afšīn | Osrušana | Arabic | 712-14 CE |

| Afšūn | Khākhsar (modern Do’rmontepa, a locality 20 miles west of Samarkand) | Sogdian | 722 CE |

Although these titles have been proposed to stem from *xšaēta “radiance brilliance” (whence Persian šīd), the Old Iranian *xšáyati “king, ruler” is more likely to be the origin. According to B. Gharib’s Sogdian-Persian-English dictionary, the origin of Afšīn is specifically *xšaēwan containing the elements *xšay “to dominate, to rule” and -wan(ē) “doer”, equivalent to Proto-East-Iranian *xšaivanaka. The fronting of initial /x/, /xᵛ/, or /h/ to /f/ is attested in Sogdian: e.g. Sogdian Frōm “Rome, Byzantine” cf. Middle Persian Hrōm; Sogdian farn, fan “glory, royal splendor” > Avestan xᵛarənah; Sogdian fraxrōs “timid” Avestan fraxraosya- < xroad-.

It is not difficult to infer fronting in variations of *xšaēwan, including (ə)xšēwanē > axšēwan > Afšīyan? and (ə)xšyōnē > axšōn > Afšūn? The form Afšīn, then, is akin to these, and is perhaps a variation of Afšīyan in particular. As such it is possible that only Axšīd (xšēδ) is derived directly from Old Iranian *xšáyati “king” rather than the form *xšaēwan “dominator, ruler”. It further does not exhibit fronting of the initial voiceless velar fricative /x/, which is peculiar if the inhabitants of Farghāna were part of a dialect continuum with other Sogdian speakers who had fronted the initial velar /x/ in their kindred regal titles. This is problematic in that Axšīd persists chronologically later than the other forms. Perhaps the Ixšīds of Farghāna deliberately chose their title from a more archaic word that was still known to them. Or perhaps their dialect simply escaped the sound change that took place further west. Nonetheless, Gharib’s Sogdian-Persian-English dictionary lists multiple lexemes derived from the root *xšaēwan that apparently retained the initial /x/, including a word for “queen”. In this context, it seems the fronted Afšīn and its variants would have been particularly strange:

(10651) xšāwan -> (a)xšōn: “power, rule, authority”

(10652) xšōndār: “ruler”

(10663) xšōnč, xšēwanč, xšəwanč: “queen”

Thus while we cannot know for certain, it appears most likely that the meaning of Afšīn in Sogdian was “King, ruler”, and is a relative to Persian šāh.