Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. The goal of this article is to introduce the reader to the history of Khorezm located in modern-day Uzbekistan, as well as its historic Iranian and modern Turkic vernaculars.

History of Khwarezm and its Indigenous Iranian Language

For at least two millennia until the Mongol invasion in the 13th century CE, the inhabitants of Khwarezm (Chorasmia) were of Iranian stock and spoke the Iranian Khwarezmian (Chorasmian) language. This once prominent Iranian language–attested first in royal wood and leather inscriptions at Toprak Kala (7th century C.E.) in an indigenous Aramaic-derived script, and later in al-Biruni’s manuscripts and Zamakhshari’s Arabic-Persian dictionary (Muqadimmat al-Adab)–belonged to the Eastern Iranian clade with nearby Sogdian and Saka (Khotanese, Tumshuqese, Scythian). In fact, with various settlements at Kuyusai 2 in the Oxus delta, which has been dated to the 12th-11th centuries B.C.E. by the presence of so-called “Scythian” (Saka) arrowhead, some scholars have argued that the Iranian Scythians were descended from these northern peoples and that Khwarezm was one early arena for their emergence as a distinct people. In another vein, University of Hawaii historian Elton L. Daniel believes Khwarazm to be the “most likely locale” corresponding to the original home of the Avestan people, and thereby the cradle of Zoroastrianism. Dehkhoda calls Khwarazm “the cradle of the Aryan tribe” (مهد قوم آریا mahd-e qawm-e āryā).

Zoroastrianism was the dominant religion in this oasis, as it may have been the homeland of the religion (what is called in ancient Avestic texts Airyanəm Vaēǰah lit. “expanse of the Aryans”). Remains of the massive Chilpyk Zoroastrian tower of silence (daḵma) from the 1st century B.C.- 1st century A.D. confirms the preeminence of the religion, although it is likely that similarly to neighboring Transoxiana and Khorāsān there were once Manichaean, Buddhist and Christian communities present in the first centuries A.D. There must have been a sizable Zoroastrian community in the early capital Kāth even after the arrival of Islam, from whom the scientist al-Biruni obtained the rich research data on Zoroastrianism in his Āṯār al-bāqia. As Biruni, a native of Khwarezm, verifies in his Āṯār al-bāqia:

أهل خوارزم […] کانوا غصناً من دوحة الفرس

Ahl Ḵawārizm kānū ḡuṣnan min dawḥat al-furus

“The people of Khwārezm were a branch from the Persian tree.”

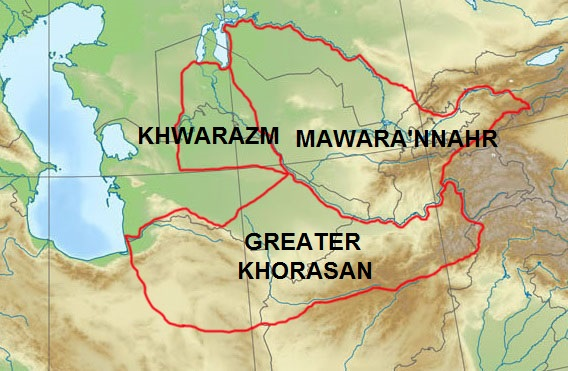

(1) A map illustrating the historic Iranian regions of Māwara’nnahr (Transoxiana), Khwārazm (Chorasmia) and Greater Khorāsān overlying modern political borders (2) Map of Khwārazm and its important settlements during the early Islamic period (3) Location of the main fortresses of the Chorasmian oasis during the Sassanian period, 4th century BC-6th century AD (4) Fortress of Kyzyl-Kala (c. 1st-4th century AD; restored), one of the many fortresses constructed when the region was inhabited by the Iranian Chorasmian people

Throughout antiquity, the fate of the Khwarezmians rested upon the unpredictable currents of the fierce Oxus river (Āmu Daryā). A large oasis region nestled in a fertile river delta where the Oxus meets the historic Aral Sea, Khwarezm’s urban settlements relied on a complex system of man-made canals and irrigation networks for agricultural growth. Its name is most likely a reference to being the lowest region in Central Asia: kh(w)ar ‘low’ and zam ‘land’. But Khwarezm owed both its glory and demise to the Oxus; due to the nearly flat plain, its cities were frequently flooded when the river changed course. This was particularly felt in the early capital city of Kāth on the right bank of the river, which at its zenith in the 10th century CE apparently rivaled the cities of the Iranian plateau. According to Biruni, who eye-witnessed the flooding of his hometown Fir, a suburb (birūn) of Kāth, before his emigration at the age of twenty-five (in 998 CE), Fir “was broken and shattered by the Oxus, and was swept away piece by piece every year, till the last remains of it had disappeared” in the year 1305 of the Seleucid era (994 CE) (Biruni, Āṯār, tr., p. 41).

During the reign of Shapur I, the Sassanian Persian Empire extended its territorial boundaries to encompass Khwarezm. Historical sources, such as Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī, confirm Khwarezm’s status as a regional capital of the Sassanid empire, with references to the pre-Islamic “Khosrau of Khwarezm” (خسرو خوارزم), Islamic “Amir of Khwarezm” (امیر خوارزم), and the Khwarezmid Empire. These sources explicitly indicate that Khwarezm was a part of the Iranian (Persian) empire, and the conquest of significant areas of Khwarezm during the reign of Khosrow II further supports this assertion. Moreover, Al-Biruni and Ibn Khordādbeh, among other sources, attest to the use of Pahlavi script, which was employed by the Persian bureaucracy in conjunction with the local Chorasmian alphabet around the 2nd century AD.

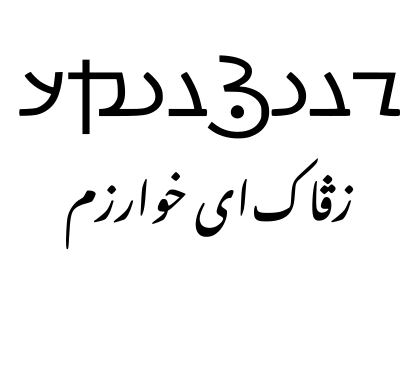

(1) Khwarezmian frescoes from Kazakly-Yatkan fortress (1st century BC-2nd century AD), modern Republic of Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan. Ancient Iranians in Central Asia made frequent use of cosmetics, as depicted in the figure’s full red ears and lips, thick eyebrows and eyeliner (2) Ruins of the massive Chilpyk Zoroastrian Tower of Silence (daḵma) from the 1st century B.C.- 1st century A.D, Republic of Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan (3) The native Iranian Chorasmian (Khwarezmian) language was likely spoken at least until the Mongol conquest in 13th century A.D., after which it was definitively supplanted by Persianized Turkic dialects and Persian. The language first employed a script derived from Pahlavi and after Islam, a modified Perso-Arabic script. Both scripts read: zβāk āy xwārazm “Khwarezmian language”

The arrival of Islam in the 8th century A.D. delivered a catastrophic blow to the Iranian Chorasmian language, identity and the native Zoroastrian religion in the oasis. According to al-Biruni, the Arabs systematically annihilated the strongholds of the religion, punished those who retained competency in their language and culture, engaged in massive-scale book burning and massacred the region’s scholars and literati. Speaking to the fate of Khwarezm after the Arab conquest, al-Biruni lamented:

When Qutayba ibn Muslim under the command of Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf was sent to Khwarazmia with a military expedition and conquered it for the second time, he swiftly killed whoever wrote in the Khwarazmian native language and knew of the Khwarazmian heritage, history, and culture. He then killed all their Zoroastrian priests and burned and wasted their books, until gradually the illiterate only remained, who knew nothing of writing, and hence the region’s history was mostly forgotten.

Khwarezm became increasingly Turkicized in the centuries after Islam, particularly after 1044, when it came under the Seljuqs (Tolstow, pp. 290-92). At the same time, however, Persian language was asserting itself in the same area (Spuler, 1966, p. 171), although the indigenous (Middle) Iranian languages Sogdian and Chorasmian were also still spoken (Henning, “Mitteliranisch,” pp. 56-58, 84). With the fall of indigenous Iranian dynasties including the Afrighid and Ma’munid lines, the title of Khwarezmshah was assumed by the Turks, but court life and high culture was conducted in Persian, as confirmed by existing chancery documents authored by a reputable Persian poet Rashid al-din Vatvat who lived at the court in Gurganj. Additionally, the fact that Khwarezmshahs such as ʿAlā al-Dīn Tekish (1172–1200) issued all of their administrative and public orders in Persian further corroborates Al-Biruni’s claims of the status of Persian in the oasis. It appears that the autochthonous Iranian Chorasmian language was still in use in the 13th century A.D., but it disappears from the record following the Mongol invasion of the region. In contrast to the valleys and major oases in Transoxiana such as Bukhara and Samarqand which retained Persian as the dominant language, a deeply Persianized Turkic (Chaghatai) emerged as the dominant language in Khwarezm, while Persian was used as a language of literature, poetry and administration.

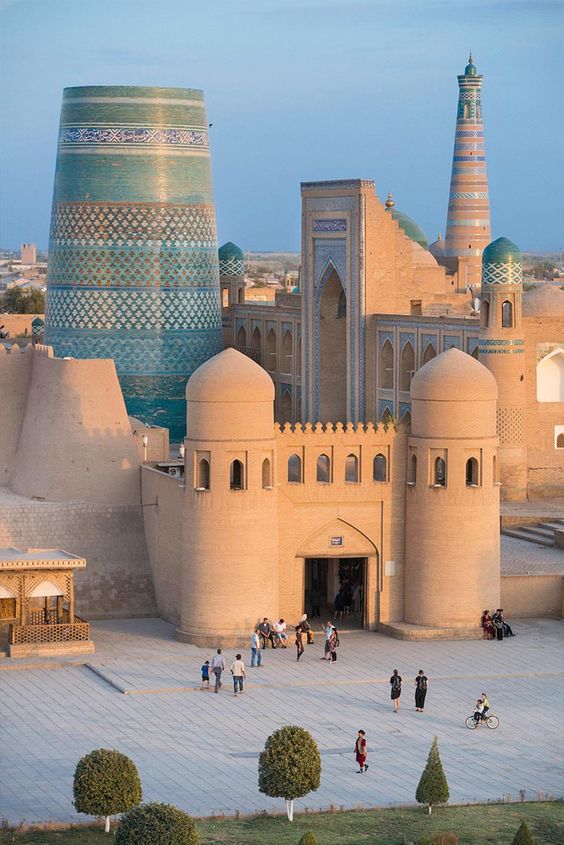

A band of glazed azure majollica tiles with an inscription in Persian in nastaʿlīq script adorns the top of the unfinished Kalta Minor, Khiva, Uzbekistan (c. 1851 AD). The minaret and the madrasa that adjoins it were commissioned by the Uzbek Qongrat ruler, Muhammad Amin Khān, who originally planned to build the highest minaret in the world. The poem reads in Persian:

منار عالی فرخنده بنیاد که مانندش ندیده چشم افلاک

Menār-e ‘āli-ye farḵonde bonyād ke mānandash nadide chashm-e aflāk

عمارت شد بامر شاه عالم ز جمله عیبها و نقص ها پاک

‘Emārat shod be amr-e Shāh-e ‘ālam, ze jomle ‘aybhā va naqṣhā pāk

بچشم عقل در وقت نمودش شده سرو سهی مانند خاشاک

Be chashm-e ‘aql dar vaqt-e nemudash shode sarv-e sahi mānand-e ḵāshāk

چو از طوبی آمد دلگشاتر به جنت کرد نادرش عرضه خاک

Cho az ṭubā āmad delgoshātar be jannat kard nāderash ‘arze-ye ḵāk

رسیده چون ستون بر كاخ گردون ز وصفش قاصر آمد عقل و ادراک

Raside chun sotūn bar kāḵ-e gardūn, ze vaṣfash qāṣer āmad ‘aql-o-edrāk

از این در آگهی سال بنایش رقم کرده ستون خاک افلاک

Az in dar āgahi-ye sāl-e banāyash raqam karde sotūn-e ḵāk-e aflāk

Chingis Khan’s conquest of the Khwarezmid empire dealt a fatal blow to the region from which it would never fully recover its former eminence. Its cities, including the imperial capital of Gurganj, were systematically flooded by destruction of the region’s ancient dams, and the majority of Khwarezm’s population was executed by the Mongol horde. Several thousand craftsmen and soldiers who escaped the sword were deported to the China, where they established a thriving diaspora community that persists in present times (for further reading about China’s Hui community, see here). The decimation of the ancient Iranian population of Khwarezm created a vacuum that occasioned the gradual influx of nomadic Turko-Mongol peoples, some of whom maintained their nomadic lifestyle over the centuries, while others came to settle in newly constructed urban centers where they adopted Persian culture. Khwarezm was originally assigned to the Chaghatayid dominion and later–following devastations by the Golden Horde and Timurids– came under the control of a local Jochid-line clan ‘Arabshāhids. Reflecting on the Mongol invasion, the Persian poet Anvari writes:

آخر ای خاک خراسان داد یزدانت نجات

Āḵar ey ḵāk-e Ḵorāsān dād yazdānat nejāt

“Oh land of Khorāsān! God hath saved you,

از بلای غیرت خاک ره گرگانج و کات

Az balā-ye ḡeirat-e ḵāk-e rah-e Gurganj o Kāt

from the disaster that befell the land of Gurganj and Kāth [Khwarezm]”

—Divān of Anvari

(1) The inner shell of the dome covering the hexagonal main hall of the Turabek Khānum Mausoleum. The surface is covered in colorful Persian mosaics depicting ornamental patterns of flowers and stars; a visual metaphor for the heavens (2) The partially-restored mausoleum of Turabek Khānum, wife of Qultugh-Temür (ruled between 1321 and 1336). The capital of the Khwarazmshahid dominion, Gurganj (modern Urgench, Turmenistan) was destroyed and its entire population annihilated at the hands of Genghis Khan

Following the demise of the ‘Arabshāhids, various khans were brought from the steppes to Khiva where they held the reins of power, usually as puppets, while the actual authority was wielded by the inaq, or military chief, of the Mongol Qongrat clan. In the 18th century A.D., nomadic Karakalpaks–a Kipchak people closely related to Kazakhs–settled in the lower reaches of the Āmu Daryā and its delta with the Aral Sea, dotted with the ruins of innumerable fortresses, settlements, and Zoroastrian buildings of ancient Khwarezm, while the upper shores of the river and its watershed have been inhabited by Persianized, mixed Oghuz-Karluk-speaking peoples through modern times. The region came under the control of imperial Russia, and the Soviet era saw the creation of the short-lived People’s Republic of Khorezm (Khorezm SSR; Хорезмская Народная Советская Республика Khorezmskaya Narodnaya Sovetskaya Respublika) before it was incorporated into the Uzbek SSR and thence, Uzbekistan.

There appears to be little, if any, Iranian Chorasmian substrate in modern Khorezmian Turkic. A few terms relating to irrigation (arna “large canal” and yab “small canal”), which survived only at Ḵīva and among the Turkmen are supposed by Barthold (1956, p. 15) to be of Chorasmian origin. By coincidence, Iranian Chorasmian had the dental fricatives [ð] and [θ], a unique feature which it shares with the language that at least partially supplanted it, Turkmen. The largest influence on Khorezmian Turkic is Persian (discussed below), and more recently, Russian.

-Jan al uch erkalik ba süziŋde, yuz miŋ ma’na karashiŋde, güziŋde

“There are three heart-robbing tricks in your words, there are a hundred-thousand hidden meanings in your glance, in your eye”

-Janim, mani janim sani ichiŋde, kachan-g’acha öldurasan iziŋde

“My soul, my soul is within you, until when will you kill all those who cross your path?

-San küŋlim bag’ini rahyan güli, qalbim nazirasi javahir duri

“You are a basil flower in the garden of my soul, you are a pearl worthy of my whole heart”

-Kimlar man dab aysta– aytaversinlar, sani mandin sevolmiydi hich biri

“Whoever tries to woe you like me, let them woe! None of them can ever love you more than me”

–Aksham düshümde, bir gül-i ranoni güribman

“In my dreams at night, I am holding a beautiful flower”

-Shul gül-i rano bilen bog’da yuribman

“Holding that beautiful flower, I am standing in a garden”

-Ul bog’ ichinde sorı, kızıl güller tiribmen

“In this garden, I am picking yellow and red flowers”

-Shuni yollara harna bela gelsa turibmon

“If any manner of calamity should cross his path, I shall stand my ground”

-Man bandaŋ bo’lin, ko’lıŋ bo’lin, yor, soŋo banda!

“May I become thy serf, may I be thy slave; a slave to thee, my beloved!”

-Sodog’oŋ bo’lin, sariŋa dünin, ö’rtama shuda. Kıynama beda!

“May I be thy sacrifice, may I rotate about thy head; do not interfere in this!”

Khorezmian Turkic as a mixed Oghuz-Karluk language

The main dialect is spoken in Khiva-Urgench and appears to be a mixed language, consisting of an Oghuz core with a strong admixture of Karluk elements. This language appears to descend from an ancestor close to that of the Chaghatai language. In morphology, some Karluk elements have supplanted the Oghuz elements, while in phonology and lexicon KT can in some respects be seen as closer to Oghuz than to Karluk. There is a Kipchak language spoken in Khwarezm, but it does not seem to have influenced the prestige language in Khiva-Urgench to an appreciable degree.

The largest foreign influence on Khorezmian Turkic has been Persian, a fact that is frequently underestimated when speakers compare the “Turkness” of KT to Standard Uzbek (adabiy til, lit. “literary language”) or Sarti Uzbek dialects, which by comparison are viewed as heavily Persianized. There is some truth to the idea inasmuch as KT has retained Turkic phonological features such as vowel harmony while Persian influence eradicated them from Uzbek. However, Khorezmian Turkic also contains hundreds of Persian words used in daily life, some of which do not exist in Uzbek. Like all Islamized Turkic languages among which Chaghatai, Uyghur, Azeri, Ottoman Turkish and Tatar may be enumerated, both Uzbek and Khorezmian Turkic rely heavily on Persian lexicon and formulas (calques, subordinate clauses, relative clauses) in the literary register.

A selection of distinguishing phonological, morphological and lexical features of Khorezmian is discussed below.

Phonology:

The most striking feature of KT’s phonology is the presence of vowel harmony, whereas Karluk in Transoxiana (Sarti Uzbek) lost vowel harmony under the influence of Persian (Tajik). KT has expected phonological correspondences for an Oghuz language: /d/ for Uzbek /t/ ; /g/ for uzbek /k/, i.e: Uzbek til — KT dil “language, tongue”; Uzbek tish — KT dish “tooth”; Uzbek kel —KT gal “come”; Uzbek kerak — KT garak “need”.

Khorezmian, unlike Uzbek, retains vowel harmonized modifications to the personal pronouns: i.e. KT män, maŋa “I, to me” and sän, saŋa “you, to you” for Uzbek men, menga and sen, senga, respectively. This feature is shared with Oghuz, where the presence of -g- reflects early Oghuz dative forms prior to being lost it in modern Azeri mana and Turkish bana.

| Turkish | Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| Yanıma gelib sırrını söyle | Yanıma gelib sırıŋnı sölle | Yonimga kelib siringni ayt | Come to me and tell me your secret |

| -Adınız ne? -Sana söyleceğim | -Adıŋız ne? -Saŋa sölejekmen | -Ismingiz nima? -Senga aytaman | -What is your name?-I will tell you (later) |

Like Oghuz but in contrast to Karluk, KT has an aversion for the voiceless uvular plosive /q/ which is instead approximated as the voiceless velar plosive /k/. In higher registers, /q/ is sometimes realized in an attempt to emulate Standard Uzbek phonology. When followed by rounded /a/, /q/ becomes /g’/.

| Turkish | Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| Kapkara kaşına bak, efendim | Kap-kara kashına bak, og’ojon | Qop-qora qoshiga boq, akajon | Look at her darkest black eyebrows, mister |

| Akkan su | Akkan suw | Oqqan suv | Running water |

/X/ is usually realized as /h/, like in nearby Turkmen and western varieties of Anatolian Turkish. Frequently speakers pronounce /v/ as /w/. Additionally, the Uzbek ablative suffix -dan “from” is vowel harmonized -nan/-nen in KT:

| Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| Harezmıŋ hanları hiwanan kachdıla | Xorazmning xonlari xivadan qochdilar | “The Khans of Khwarezm fled Khiva” |

Morphology:

Speakers of KT are frequently socially conscious of linkages between Khorezmian Turkic and Oghuz Turkic languages, particularly Anatolian Turkish. Khorezmian is confederate with Oghuz in use of -n- in third person genitive constructions while Uzbek lacks it. Indeed, it is possible to construct phrases which reveal the affinity of Khorezmian to Anatolian Turkish:

| Turkish | Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| Gözlerinde büyü var, elinde bal var | Güzlerinde efsun ba, elinde bal ba | Ko’zlarida afsun bor, qo’lida asal bor | There is sorcery in his/her eyes, there is honey in his/her hands |

| çiçeklerin içinde | chicheklerıŋ ichinda | gullarning ichida | inside the flowers |

Contrarily, verb endings and morphological paradigms in KT are definitively Karluk in character, with only literary use of the Oghuz styles such as -mish:

| Turkish | Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| Yediğim yemek | Yegen yemegim | Yegan ovqatim | The food I have eaten |

| Yaprağlar çok güzelmiş | Yaprag’la dım xushro’y eken | Barglar juda chiroyli ekan | The leaves are very beautiful |

Khorezmian Turkic and Standard Uzbek have variably inherited morphological features that existed in Chaghatai. For example, Khorezmian more frequently uses the focal present marker -yotir- while Uzbek favors -yap-. Of note, -yatir was consciously introduced into Uzbek in the 1920s, but its use remains confined to the literary register

| Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| Og’o galyotır | Aka kelyapti | “The man is coming” |

KT makes more use of definitive future -ajak/ejek which it shares with Oghuz Turkic, while Uzbek uses the present-future -a(y)-, presumptive future -ar and intentional -moqchi with higher frequency to indicate actions in the future

| Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| –Opojon galajakmı? –Hawa, galajak | –Onajon keladimi? –Ha, keladi | -“Will mother come?” -“Yes, she will come” |

| Et satajakman | Go’sht sotmoqchiman | “I want to/will sell meat” |

KT has the optative singular ending –in for Uzbek -ay/-ayin and the vowel harmonized optative plural –eli/alı for invariable Uzbek –aylik

| Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| Bu aksham degirmana baralı, chürek yapalı | Bu oqshom tegirmonga boraylik, non yapaylik | “Let’s go to the mill at tonight, let’s make bread” |

| Kara güzinnen aynanin | Qora ko’zidan aylanay | “I’ll ritually circulate around her black eyes to ward off harm from them” (aylanmoq is calqued from the Persian دور گشتن, گرد گشتن) |

| Nich etin | Nima qilay | “What should I do?” |

Like Oghuz, origin is expressed with -li/lı instead of Uzbek and Uyghur (Karluk) -lik, –liq respectively.

| Khorezmian Turkic | Uzbek | English |

| Hiwalı kizla bashkacha | Xivalik qizlar boshqacha | “Girls from Khiva are wonderful” |

Vocabulary:

In general Khorezmian Turkic lexicon is close to Karluk Uzbek, but contains three classes of distinct vocabulary from it: (1) Oghuz words (2) Native words of unclear origin, and (3) Persian words (including Persianized Arabic) which are present in one language but not the other.

Some examples of Khorezmian vocabulary and comparison with Uzbek are listed here: el “hand” (Uz. qo’l) , bol “honey” (Uz. asal) , et “meat” (Uz. go’sht), ne, novvi “what” (Uz. nima), nerda “where” (Uz. qayerda), nichik (Uz. qanaqa/qanday), eshik “door” (Uz. qopi), chechak “flower” (Uz. gul), yapraq “leaf” (Uz. barg), ad “name” (Uz. ism), salma “burn” (Uz. soy), taka “pillow” (Uz. yostiq), karvuch “brick” (Uz. g’isht), etmek “to do” (Uz. qilmoq), söllemek “to say” (Uz. aytmoq), dali “crazy” (Uz. devona), pitta “a little” (Uz. biroz), kadi “gourd” (Uz. qovoq), ina’ “here it is; right here; voila” (Uz. mana), mazali “beautiful” (Uz. go’zal), dim “very, a lot” (Uz. juda), xushro’y “beautiful” (Uz. chiroyli), zangi “ladder” (Uz. narvon), yimirta “egg” (Uz. tuxum), brinj “rice” (Uz. guruch).

-Kılıkları kurmag’ay, sho’xlıkları durmag’ay

“Don’t do these delightful behaviors, don’t let your naughtiness stop”

-Wakh shu kiznı azabları hichkima buyurmag’ay

“Oh goodness, do not direct this woman’s wrath at anyone else”

-Koymin sıra sho’xlıkıŋ, bılmin özda yoklıkıŋ

“May I never stop your contentment, may I never know your absence”

-Shu kiz bilen ekansin, yanib turg’an otlıkıŋ

“When you’re with this girl, your embers burst into flames”