Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. The goal of this article is to explore the origins of Moroccan Darija through the lens of local sedentary and Bedouin dialects, and to examine historic contacts with autochthonous Berber languages and foreign languages such as Spanish and Persian.

Background

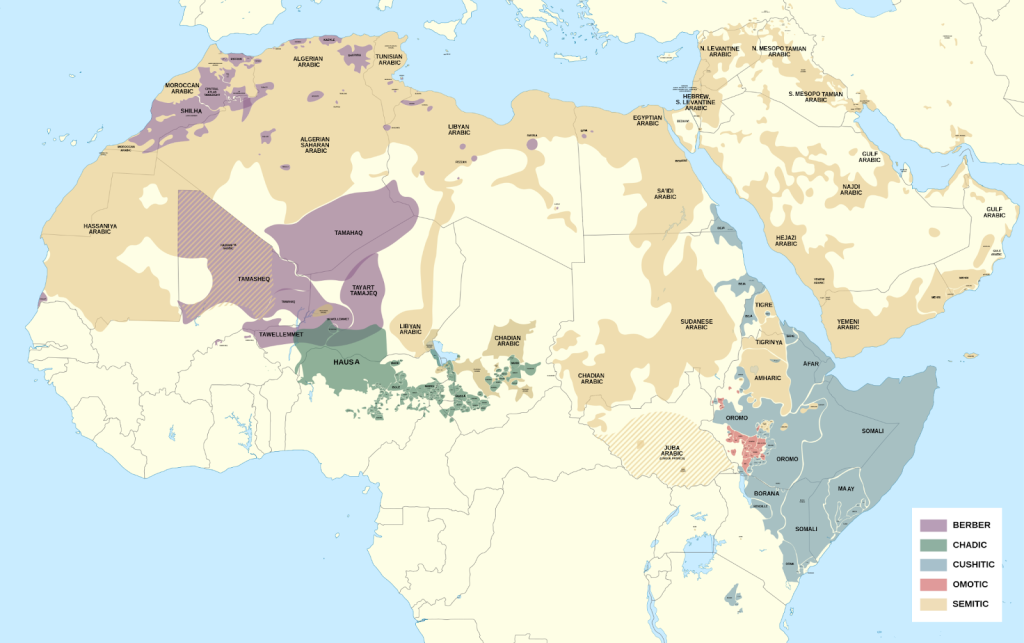

Northwest Africa (the “Maghreb”, from Arabic المغرب الاقصى al-maġrib al-aqṣa “the farthest West”; and, more recently, Berber: ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵖⴰ Tamazɣa “Land of the Imazighen [Berbers]”) experienced two waves of Arabization separated in time by nearly five centuries. Following a classification made by Ibn Khaldūn, the first wave was composed of mainly urban soldiers while the second wave brought thousands of nomadic Arabian families to the region. The number of Arabophones who arrived in both cases must have been relatively small compared to the indigenous Berber- (and, formerly, Latin-) speaking populations, and whilst many Berbers shifted to the language of their new conquerors over the centuries, this process has failed to result in the adoption of an exclusively Arab identity.

Arabic vernaculars in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia are referred to locally as Darija (lit. “vernacular language”), while the literary Arabic standard used in education, broadcast and administration is called ʕarabiyya fuṣḥa (lit. “eloquent Arabic”). Darija varieties may in turn be divided into sedentary (pre-Hilali, or مديني mdīni lit. “urban”, or حضري ħadˤari “settled”) and Bedouin (Hilali or عروبي ʕarūbi, lit. “Arabian”) dialects. However, these descriptors technically refer to the medieval “Middle Eastern” vernaculars from which they descend rather than the lifestyles of their current speakers. While there is largely direct lineage between the progenitor Middle Eastern urban dialects and Moroccan urban dialects, in some cases, they do not correspond. For example, the Jebli Arabic dialect spoken in the northwestern rim of the Atlas mountains represents a “sedentary” (Pre-Hilali) dialect adopted by Berber mountaineers along the trade routes between Fes and Tangier, which therefore links it with the old urban dialects of North Africa. Moreover, Moroccan Darija, which originated in 20th century Casablanca and is now the lingua franca of the country, is of Bedouin provenance (discussed below).

To further complicate the linguistic landscape in Morocco, sedentary and Bedouin Arabic varieties have interacted individually with neighboring Berber languages for over a millennium. The sedentary (Pre-Hilali) Arabic dialects, representing the first layer of Arabization, are the most innovative and bear the strongest morphosyntactic traces of these contacts. In contrast, Bedouin dialects by and large were influenced by Berber phonetic and semantic interferences. Another distinguishing feature of the sedentary Arabic varieties is the presence of Spanish lexica, transferred by Andalusian Muslim and Jewish refugees who were expelled from Spain during the reconquista and settled in North African cities, while the Bedouin dialects obviously escaped these influences.

Moroccan Darija, which can be used interchangeably with “Casablancan Koine”, arose recently as a product of rapid urbanization around Casablanca in the 20th century. The dialect is of Bedouin provenance, owing to the origin of most Casablancans, but it features a strong admixture of Pre-Hilali elements brought by old urban elites who migrated from Fes, Rabat, Salé, Meknès and other northern cities. It thus represents a conglomeration of diverse contact-induced changes and koineization brought about by recent demic diffusions rather than the modern iteration of any singular historically attested dialect. Although it is now the mother language of a plurality of Moroccans, there still exists a significant degree of variation within Koine speakers, owing to its rather recent genesis and the varied regional origins of its speakers. At times, such as in the case of Fessis, Koine speakers have purposefully transferred certain features of their ancestral lects (e.g. Fessi use of non-trilled [ɹ], emphasized occlusive laryngeal [ʔˤ] or [q] in lieu of Bedouin [g], and gender-neutralized second person pronoun انتينا intīna in the perfective and imperfective aspects) due to historic sociolinguistic associations between these features and urbane refinement and, thereby, prestige.

Sedentary (pre-Hilalian) Arabic dialects:

The first wave of Arabs arrived armed on horseback, apparently without their families, in the 7th century AD. This band was composed of mixed urban Arabians (presumably Meccans) and “Middle Eastern” Muslim converts–soldiers hailing from Syria, Mesopotamia, Persia, Egypt and elsewhere–who introduced complex Perso-Arabian Islamic material culture and sedentary Arabic varieties to Roman Africa, the two Mauretaniæ and Hispania. In 670 A.D., the city of Kairouane (from Middle Persian 𐭪𐭠𐭫𐭥𐭠𐭭 kārawān “military column; caravan”) was established as a headquarters for the Muslims’ expansionist ambitions in the region, wherefrom they “plunged into the heart of the country, traversed the wilderness in which his successors erected the splendid capitals of Fes and…[Marrakesh], and at length penetrated to the verge of the Atlantic and the great desert” (Edward Gibbon).

It appears that the newcomers, apparently numbering only in the few thousands, exchanged extensively with their Berber-speaking neighbors, who must have greatly outnumbered them. In the culinary sphere, they were introduced to local foods (Berber ⵙⴻⴽⵙⵓ seksu → Arabic كسكسو ksksu “couscous”) and in return, they transferred tastes from the orient (particularly Persian cuisine, discussed below). However, owing to the very fact of their small numbers, apparently not enough correct Arabic input was available to language learners, which resulted in significant interference from Berber in the learning process. For example, it has been suggested that the agentive “m” prefix arose due to overgeneralization of a corresponding Berber agentic prefix (ⴰⵎ am-) with a broader scope of use in the first stages of language learning (e.g. مزيان mzyān “good” from زين zayn; including exceptional cases that are actually derived from Berber roots; e.g. Shilha ⴰⵎⵥⵍⵓⴹ amẓluḍ “poor” → مزلط məzluṭ “poor”). The extension of the “fəʕʕal” class of nouns–an unproductive form limited only to occupations in Classical Arabic (e.g. نجار nəjjār “carpenter”)– was probably an attempt by Berber bilinguals to use what they thought was the correct Arabic participial form (e.g. Darija خواف xəwwāf “”fearful”).

This wave was followed by a period of intense Islamization of the “pagan” autochthones, whilst per Quranic prescriptions the ahl al-ḏh̲imma (Iberian Christians and Jews, Berber Jews) were largely left alone. For centuries thereafter, Arabs and Berbers lived in uneasy communion with each other–the latter frequently serving as clients to the former–until various Berber-led rebellions toppled the Umayyad Caliphate by the middle of the 8th century. Arabic vernaculars remained essentially confined to the cities which the Arabs inhabited, whereas in the countryside, Berber languages remained the means of inter-community communications until present times. In the 9th century after the foundation of Fes, the capital of the Idrisids, Arabic became more prestigious with thousands of refugees from Andalusia and Kairouane arriving in that city and founding great mosques and madrasas (al-Andalusiyyin “Andalusians” and al-Qarawiyyin lit. “Kairouanians” mosques, c. 859 A.D.). In a sociolinguistic sense, this influx meant there was suddenly enough native Arabic input available to learners, as well as a social motivation to speak “pure” Arabic, which favored the eradication of salient Berber transferrences. It probably served to reverse the process of creolization in urban dialects which had been underway before this period. However, the few exceptional items which survived were probably too frequent by that time to be leveled by prescriptive Arabic influences (e.g. مزيان mzyān “good”; جوج juj “two”; imperative اجي aji “come!” through elimination of irregular تعال taʕāl “come).

The urban Arabic dialects in Morocco which descend from the first wave of Arabization include those of Fes, Salé, Rabat, Meknès, Marrakesh, Tétouane, Chefchaouen, Tangier, Ouazzane, Taza, as well as the Jebli dialects in the Rif region. Across modern political borders, the dialects of most old cities in the Maghreb (Tlemcen, Constantine, Tunis, Kairouane, Oran, Tripoli etc.) are included in this group. Although a minority dialect, Fessi is today considered a prestige dialect in Morocco inasmuch as it is associated with the landed aristocracy that has mostly migrated to Casablanca within the last century, drawn by the numerous French language schools there. The core vocabulary of the urban Arabic varieties in the Maghreb often corresponds to urban dialects further east, such as in the case of Fessi Arabic, vis-à-vis Casablancan Koine which is of Bedouin provenance:

| English | Moroccan Darija | Fessi Arabic | Damascene Arabic |

| “He did” | dār | ɛamal | ʕamal |

| “I liked” | bġit | ḥabbit | ḥabbeyt |

| “heart” | gəlb | ʔalb* | ʔalb |

| “What’s your name?” | ašnu smītek | šnu ʔesmek | šu ʔesmek |

| “Listen!” | ṣnnit | smaʕ | ismaʕ |

| “Good” | mzyān | mliḥ, mzyān | mniḥ |

| “Here! (take this!)” | hāk | khūd | khud |

Pre-Hilali dialects like Fessi and, through influence, Casablanca Koine, make the most use of analytic morphology such as the analytic genitive instead of the constructed genitive which is used in ʕarūbi lects. A few salient Pre-Hilali morphologic innovations are listed below:

- In Koine, the constructed genitive is no longer productive and is used only in certain relatively frozen constructions, having been replaced by dyāl or d– (e.g. L-malek d’l-mghrib “The King of Morocco”).

- Some ʕarūbi glosses with the constructed genitive are preferred in Koine (akhūti “my brothers”) in contrast to the more innovative Pre-Hilali forms used in the northern city dialects (khāwa dyāli “ibid.”)

- Analytic elatives using ktar “more” have replaced the Classical Arabic afʕal construction : bnīn ktar “tastier” instead of *abnan.

- Indefinite singular nouns employ a gender neutralized prefix واحد ال waḥd l- in lieu of a gendered suffix (this development parallels the Medieval Baghdadi prefix فد fad “a” from فرد fard)

- An analytic dual construction emerged which has supplanted the inherited dual case. It uses the word جوج juj “two” (from Classical Arabic زوج zawj “pair; couple” > Greek ζεῦγος zeûgos “yoke” via Aramaic ܙܘܓܐ zawgā).

- The feminine singular designation for inanimate plurals in Classical Arabic was replaced by masculine gender and plural number: bināyāt zuwīnīn “beautiful buildings”.

| English | Moroccan Darija | Modern Standard Arabic |

| “Beautiful things” | Shiḥwāyej zuwīnīn | Ashyāʔ jamila |

| “Many things” | Bzzāf dyāl ḥwāyej | Ashyāʔ kaṯīra |

| “Tasty, tastier” | Bnīn, bnīn ktar | Laḏīḏ, alaḏḏ |

| “One man” | Waḥd r-rajel | Rajul wāḥed |

| “Two women” | juj d’l-ʕiyālāt | imraʔatān |

| “Our house is more beautiful than their house” | D-dār dyālna zuwīna ktar mn d-dār dyālhum | Baytuna ajmal min baytihim |

As in other dialects, new native formulations arose, albeit with little concordance with the eastern Arabic idioms: باش bāš “in order to”, from بِأَيِّ شَيْء (biʾayyi šayʾ, “with what thing”);

لاباس labās “well, good” from Arabic لَا بَأْسَ (lā baʾsa), the verbal noun of بَؤُسَ baʾusa “damage, calamity”; كاين kāyin “there exists” (from كائن kā’en “existing”; cf. Medieval Baghdadi Arabic اكو aku from يكون yakūn). Some further innovations include:

- Use of ka- or the variant ta- for progressive tense; e.g. ka-nktəb “I write”, ta-tbġini “You love me”

- The future tense is constructed using ġādi or simply ġa- (cf. Classical Arabic ġadan “tomorrow”)

- First person marker with n- and first person plural use of prefix n- + suffix -u; e.g. nmši “I go”, nmšiu “We go”

- Use of feminine 2nd person perfect verb endings (-i) (note: Pre-Hilali dialects use an immutable pronoun intīna with the masculine 2nd person perfect verb ending)

| English | Moroccan Darija | Muslim Baghdadi Arabic | Damascene Arabic |

| “I just came to tell you that I love you very much” | Ġīr jīt bāš ngullək ka-nbġīk bzzāf (variant ta-nbġīk) | Bas ijeet ʕalamud agullak innu āni aḥebbek hwāye | Bas ijet ʕashān aʔullak innī baḥebbak ktīr |

| “There is or there isn’t” | Kāyen wla ma kāyenš | Aku lo māku | Fī aw mā fī |

| “I will dance too” | Ḥta ana ġādi nšṭaḥ | Āni ham raḥ arguṣ | Ana raḥ arʔuṣ kamān |

| “Because” | Ḥet, ḥetāš | liʔan | leʔannu |

| “We wanted to sleep there” | Kenna nbġīu nnəʕʕsu təmmāk | Činna nrīd ənnām əhnāke | Kān biddna nnām hunīk |

| “If you were a true Moroccan, you shouldn’t have sold your country to foreigners” | Kūn kenti maḡribi quḥḥ, kūn ma bʕtiš l-blād dyālek lgwar | Lo činit maghrebi ḥaqiqi, ma chān baʕet blādek lil faranj | Iza kent maghrebi ḥaʔiʔi, ma kān beʕt baladak lil faranj |

On the Persian Elements in Morocco

Old urban dialects, such as that of Fes, have imbued Moroccan Darija with words of early imperial Islamic origin which recall the Orient, including: بالزاف bzzāf “very; a lot” (from Classical Arabic بالجزاف bil jazāf, itself from Persian گزاف gazāf “exaggerated, excessive”) and ڭاوري gāwri (from Persian گاور gâvor “Zoroastrian from Mesopotamia”; later adopted by the Muslims meaning “infidel”), كفتة kafta (from Persian كوفته kūfte, كوفتن kūftan “to beat, grind, shatter”), شوربة shurba “soup” (from Persian شوربا šurbâ “a kind of stew”, lit. “salty/sour stew”); مݣانة magāna “clock, watch” from Persian پنگان pengān “water clock” (cf. Tunisian Arabic منڨالة mungāla), شرجم،سرجب sarjam/sharjab “window” from Persian چارچوب čârčub “frame”; note Libyan Arabic روشن rōšan, “window” from Persian روزن rowzan “crevice, hole”); بزطام bizṭām (cf. Algerian Arabic تزدام tezdām) from Persian جزدان jozdān “wallet”; سطوان siṭwān “tiled courtyard surrounded by peristyle within the house” (from Persian ستون sotun “column”); خرشوف xarshūf “artichoke” (from Middle Persian 𐭤𐭠𐭫𐭰𐭥𐭯 *xār-čōp, lit. “thorny stick”), خمم xemmem “to think” (irregular variant with -m final of Classical Arabic خمن xammana “to guess, suspect”, maybe ultimately an assimilated root from Persian گمان gumān “supposition; speculation”). Urban dialects like that of Salé have preserved other Abbasid archaisms, such as مارستان māristān “hospital”, from Persian بيمارستان bimārestān.

(1) A Moroccan man clad in traditional striped jeleba fills a bottle of water at Fontaine Nejjarine, Fes, Morocco (c. 18th century) (2) Horseshoe arches with polychrome glazed tiles decorate the Bab Bou Jeloud (built by the French in 1913), with a view of the Bou Inania minaret and old medina, Fes, Morocco (3) Polychrome glazed tiles with geometric motifs, resembling those in Persian architecture, at Dar el Bacha museum, Marrakesh, Morocco (4) The author (right) and his brother in Fes, Morocco (c. 1998)

The presence of Iranian loans at first seems unbewildering given the many hundreds of Persian words that entered the Arabic language–either directly or via Aramaic– following the Islamic conquest of the Sassanid Persian Empire. Persian, Greek, and Aramaic represent the largest loaner languages to Classical Arabic, although frequently only the latter two are emphasized. Persians played a seminal role in the standardization of Arabic as a literary medium and pioneered the academic study of the language; indeed the Arab historiographer Ibn Khaldūn could barely restrain himself from singing the praises of Persian grammarians, physicians, astronomers, mathematicians and other scholars in developing what has frequently been referred to as “Arabian” or “Islamic” science. These lexemes are unique however in that many are unattested in the Arabic vernaculars further east, and this taken in conjunction with the material and onomastic evidence detailed below suggests the presence of a small but influential Iranian element in early Islamic North Africa.

In light of the drastic shortage of historical records on these migrations, the presence of Persian names among intellectuals and dynasts of the Islamic period in North Africa lends credence to that idea. Apparently their descendants founded two dynasties in the Maghreb–the Rustamids (Bānū-Bādūsyān, 777-909 A.D), founded by ‘Abd al-Raḥmān ibn Rustam, were Persian Ibāḍī imāms whose capital Tahert in modern-day Algeria was famed as ‘Iraq al-Maghrib “Mesopotamia of the West”, or Balkh al-Maghrib “Bactria of the West”, perhaps owing in part to the Iranian character of the city. A century later, the Khurāsānid dynasty (Bānū-Khurāsān, 1059-1148 A.D.) founded by ‘Abd al-Ḥaqq ibn ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn Khurāsān, ruled an independent principality in modern-day Tunisia. Persian immigrants or those with Iranian nisbahs further appear in Andalusia (Ziryāb, al-Shushtari), detailed below.

It is notable that west of Baghdād (from Middle Persian 𐭡𐭢𐭣𐭲 (bgdt /bag-dād/, “given by god”; compare Russian given name Богда́н Bogdan “ibid.”), nowhere in the medieval Islamic world did Iranian forms gain as much currency as in the Maghreb. Perhaps this owed in part to the nature of urbanity in Anatolia, Egypt, Palestine and Greater Syria, where for centuries the materials of Greco-Roman civilization reigned supreme among a Romanized Christian citizenry. Indeed Roman churches and other buildings in these regions were frequently dismantled by the Muslims for reusable materials or repurposed into mosques by the simple addition of a mihrab and minaret (e.g. the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus which was formerly the Basilica of Saint John the Baptist (Greek: βασιλική του Αγίου Ιοάννή του Βαπτιστή Vasilikí tou Agíou Ioánni tou Vaptistí). Islamic architectural forms in these regions employed nearly identical building materials (limestone ashlar) and ornamentation schemes (marble veneer decorations, Greek order columns) to the forms that preceded them, which were Roman in character.

The Maghreb was instead relatively virgin land for the Muslim immigrants, who founded a significant number of new cities which they cohabited with Berbers. These new spaces engendered the transmission and local innovation of Persislamic architectural vocabulary, fashions and culinary stylings. For example, the adoption of the Persian garden form (Arabic: رياد riād; Persian: چهار باغ chahār bāgh) was most marked in the Maghreb, and it became a prominent feature in Moorish palaces in Spain (such as Madinat al-Zaḥrā, the Aljafería, and the Alhambra). In the 9th century, Persians had discovered the manufacture of colored tiles with metallic pigments through the use of tin oxide glaze, which spawned a renaissance of majollica tile production in the Iranian world that apparently also reached the Maghreb. The technology and inspiration behind zellīj tiles in the Maghreb is, thus, undoubtedly Persian, rather than the untenable idea that Roman mosaics which are composed of tesserae and depict human and animal forms somehow circuitously inspired Maghrebi Islamic zellīj. The latter hypothesis is further problematic in that it forces us to accept the unlikely scenario that Persian and Maghrebi tilework, with their strikingly similar compositions and designs, developed twice around the same time and independently of each other. Why this art would not have developed in Syria, Palestine or Egypt, where Roman and Byzantine mosaics existed in great volume, is another perplexing question.

Evidence of Persian craftsmen and architects exporting their crafts abounds in the Arab world; for example, the glazed tiles on several Cairene buildings, including the bulbous stone minarets of the mosque of Nāṣer Moḥammad in the citadel (1318-35 A.D.), indicate that craftsmen from Tabrīz operated a workshop in Cairo in the 1330s and 1340s. Double-shelled, ribbed domes ending in muqarnas corbels (stalactites) with high, calligraphy-ornamented drums are Persian features to be see on the Mausoleum of al-Ṣultaniyya in Cairo, and which are later encountered in Timurid Samarqand. The characteristic Persian four-ayvān plan was first introduced to Mamlūk Egypt in madrasas, though it was rarely, if ever, used in mosques there, but is frequently encountered in the Maghreb. Morever muqarnas vaults, a prominent Persian feature in Maghrebi architecture, were only seldom commissioned in Syria and Egypt, but took strong hold further west where they are carved into stucco. Since in Morocco many buildings were constructed using baked earth or bricks–much like in Persia–geometric ornamentation schemes using glazed tiles or carved plaster or stucco resembling those in Iran could be applied to buildings. This contrasts with the situation in Egypt, Anatolia and Syria, where limestone ashlar buildings with marble veneer decorations predominated. Thus, Persian elements appeared frequently in Maghrebi architecture, probably as a result of the presence in North Africa of individuals with firsthand experience of Persian architecture.

Moroccan culinary tradition attributes the widespread use of nuts like almonds and cashews, dried fruits such as raisins, prunes, dates and apricots, pickled lemons (حامض مصير ḥamudh mṣir) and saffron to Persian influence. Indeed, both cuisines are characterized by an idiosyncratic sweet, savory and sour palette, in contrast to the cuisines of their immediate neighbors. Moreover, it is known that Muslims introduced saffron from Persia to North Africa in the 10th century. This, too, points to a tunneling of early Persian forms across Romanized territories to the Maghreb, perhaps through the milieu of few but influential Iranians among the Muslims.

Andalusian Influence

In the 15th century, the aforementioned old Maghrebian cities (particularly Tangier, Fes and Rabat, and more broadly Constantine, Tlemcen, Kairouane, Tunis, Tripoli and Bizerte) saw a massive influx of Muslims and Jews who had been expelled from Islamic Spain (Arabic: الاندلسيين “Andalusians”; Spanish: moriscos “Moors”) and migrated “back” to the Maghreb where they settled among their distant dialectal cousins. This “second urbanite wave” further contributed to the evolution of urban dialects, but not the ʕarūbi (Bedouin) dialects which were spoken in the countryside. Andalusian families, still distinguished by their surnames–Jorio, Fenjiro, Chkalante, Guedira, Gharnaṭa, Qorṭoubi, Andalousi, Prado, Vergas, Lavra–brought features of Spanish and Andalusian Arabic to the local vernaculars. The طرب أندلسي ṭarab ʾandalusī (and by extension غرناطي gharnāṭi in Tlemcen, from the Arabic name for Granada) is attributed to a certain Ziryāb, a freed Persian slave-turned-courtier and musical pioneer who introduced Persian instruments and musical modes to Muslim Spain. The Andalusian repertoire, with its foundations in classical Persian and Spanish music, is thus distinguished from ʕarūbi (what has been termed shaʕbi “folk”), Gnāwa and Berber folk music, which employ different instruments, formats and modes. The Gnāwa repertoire in particular, which features the guembri lute and the call-and-response format of vocal performance, links it with the musical systems of the Songhay in Timbuktu, Gao and Djenné.

A number of old Iberian Romance words entered the Fessi dialect, the legacy of large numbers of Andalusian Muslim and Jewish refugees who migrated to Maghrebian cities after their expulsion from Islamic Spain, some of which have been adopted in Casablancan Koine. These include سيمانة simāna “week” from Spanish semana; Fessi كوشينة kušina “kitchen” from Spanish cocina (doublet with darija كوزينة kuzina, probably a later borrowing during the Spanish protectorate); اشكولة iškuila “school”; from Spanish escuela; قرة qirra from Spanish guerra “war”; فورنو furnu “oven” from Spanish forno; شلية šelya “chair” from Spanish silla; طابلة ṭabla “table” from Spanish tabla; فيشطة fishṭa “party”, from Spanish fiesta; كريلو grīllu “cockroach” from Spanish grillo “cricket”; قميجة qamija “shirt”, from Spanish camisa; بسطيلة basṭila from Spanish pastilla “puff pastry with various fillings”; فابور fābor “free [of charge]; a favor” from Spanish favor; rwina from Spanish ruina “mess, wreck”, qīmrūn “shrimp” from Spanish camarón. Cities like Salé in which Andalusian immigrants settled saw propagation of Spanish words even their core vocabulary, which have not been transferred into Koine owing their salient foreign nature:

| English | Salawi Arabic (Salé) | Spanish |

| “Good” | buinu | bueno |

| “Wrong” | falṣo | falso |

| “Luck” | as-suirti | suerte |

| “Alone” | ṣulu | solo |

Some Andalusian Jews in Morocco retained their Spanish vernaculars (Ladino and Ḥaketía) until their exodus to Israel in the mid 20th century.

Bedouin (Hilalian) or ʕarūbi Dialects: the Basis of Moroccan Darija

The second wave of Arabic speakers were Bedouins of the Banu Maʕqil Banu Hilal, Banu Sulaym and Bani Ḥassan tribes who migrated en masse in the 11th and 12th centuries from the Najd region of Arabia to the Magrheb, where they took home in the arid plains and hautes-plateaux. The impetus for this forced migration was the Fatimid Caliphate’s desire to confine the unruly Bedouins in the south of their dominion. As the Bedouins were unaccustomed to urbanity, the Banu Hilal settled in areas where they continued their nomadic lifestyle, and this wave brought significantly greater linguistic arabization and spread of nomadism in areas where agriculture had previously dominated. Camps (1983) estimates the number of Bedouins to have been relatively small; only around 80,000 at the outset, and their migration extended over two centuries and not all of them settled in Morocco. Local Berbers (most likely belonging to the Masmuda confederacy and thus speaking a language related to Shilha, given the Bedouins’ settlement in the lowlying plains between Souss and Rabat), who shared a similar lifestyle of pastoralism, were quickly assimilated to the language of the incomers. The nature of their contact was such that over time, Arabs adopted the modified Arabic language of their Berber neighbors and started to speak it amongst themselves. Moreover, everyone in the community adopted the Berbers’ speech and spoke it to the children. With the establishment of Casablanca, ʕarūbi migrant workers and their dialects–rather than the old sedentary dialects such as Fessis–became the basis of Moroccan Darija. The modern Moroccan Darija is therefore a dialect of Bedouin provenance with an admixture of local sedentary features.

In contrast to the sedentary dialects which use the local innovation ka- or ta-, ʕarūbi dialects particularly in northeastern Morocco and Algeria developed a progressive aspect marker and by extension copula -را rā– (lit. “he saw”), probably from Najdi ترا tarā “to be seen”– : e.g. rāni nkteb = “I am writing” (lit. “He saw me writing”); rāk mn wjda “you are from Oujda”. Some comparisons between Moroccan Darija and Najdi Arabic are made below:

| English | Moroccan Darija (Oujda) | Najdi Arabic |

| “Youth, young generation” | drāri | dhrāri |

| Interrogative particle | wəš | weš |

| “What my heart wanted (f.)” | Lli bġaha gəlbi | Illi bġaha galbi |

| “Take this” | hāk | hāk |

| “She is going” | Rāha tmši | Tarāha temši |

With regard to Berber elements in ʕarūbi (Bedouin) dialects, examples of both metatypy and phonological restructuring exist, which is possible in extended and complex contact situations. The Arabization process presumably started with the Arabs’ neighbors, and then these Arabized Berbers served as intermediaries to their next neighbors, etc. A few examples of Berber metatypy in ʕarūbi are listed below:

- The Berber feminine/diminutive circumfix ta….t used mainly with nouns of occupations in Moroccan Darija (e.g. bənnay “mason” –> tabənnayət “profession of masonry”) but also for abstract noun derivations, e.g. dərri “child” –> tadərrit “childhood”

- The Berber genitive marker n “of”, though limited to some kinship terms like bb°a n Sufiān “father of Soufiane”

On Berber (Amazigh) influences in Darija

Berber (endonym: ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ tamazīɣt; Ar. الامازيغية al-amazīġīyya; الشلحة aš–šilḥa) is a distinct language family belonging to the Afro-Asiatic phylum. Blench (2018) notes that Berber is considerably different from other Afroasiatic branches, and indeed its genetic relation to Arabic–of equal magnitude to its relation with Ancient Egyptian and Cushitic–is vanishingly remote. Proto-Berber probably split from a common ancestor with the other known Afro-Asiatic branches between ~10,000-9,000 years before present, and then this group underwent a putative linguistic bottleneck as recently as ~3,000 years ago, which apparently eradicated the internal diversity of the family and left a contracted number of idioms from which all of the modern Berber languages descend. Proto-Berber then appears to have spread across a vast area from the western banks of the Nile river to the Atlantic coast of North Africa. Today, an estimated 30-40% of Moroccans, 20-30% of Algerians, 5-10% of Libyans and 1% of Tunisians use a Berber language as a mother tongue, but these numbers would have been higher only a century ago.

The region was visited from an early date by seafaring Phoenician merchants from the Eastern Mediterranean (but, apparently, few Greeks), who established important port colonies (e.g. Shilha ⴰⴳⴰⴷⵉⵔ Agadir, from Phoenician 𐤂𐤃𐤓 gādīr “wall;compound”, cognate with Arabic جدار jidār “wall”; Rusadir from Phoenician 𐤓𐤔𐤀𐤃𐤓 rushādir “powerful). These immigrants later established the Carthaginian empire and perpetuated Punic language and culture, eventually subjugating the Romanized para-Berber kingdom of Numidia. The presence of Punic borrowings in Proto-Berber points to the diversification of modern Berber language varieties subsequent to the fall of Carthage in 146 B.C.; only Guanche and Zenaga lack Punic loanwords. Berberophones along the Mediterranean coast later became subjects of the Roman Empire under administrative divisions of Tripolitania, Africa, Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania Tingitana, but commercial and cultural exchanges between Romans and Berbers along the Līmes Mauretaniæ persisted for centuries through the Byzantine period.

During this age of contact, Roman innovations including the ox-plough, camel (Kabyle: ⴰⵍⵖⵯⵎ a-lɣəm via metathesis from Latin camēlus or Coptic ϭⲁⲙⲟⲩⲗ (camoul)?), and orchard management were adopted by Berber communities. Latin loanwords in Berber include, notably, ⴰⴼⵓⵍⵍⵓⵙ afullus “chicken” (from Latin pullus); ⴰⵙⵏⵓⵙ asnus “donkey” (from Latin asinus), ⵓⵔⵜⵉ urti “garden” (from Latin hortus); ⵜⴰⵖⴰⵡⵙⴰ taɣawsa “thing” (from Latin causa “reason/case; motive”); ⴰⵏⵖⴰⵍⵓⵙ anɣalus “angel, spiritual entity” (from Latin angelus); ⵉⴳⴻⵔ iger “cultivated field” (from Latin ager); ⵜⴰⴼⴰⵙⴽⴰ tafaska “feast/religious celebration” (from Latin pascha “Easter; Passover”); ⴰⴼⴰⵍⴽⵓ afalku “bearded vulture” (from Latin falcō “falcon”), ⵜⴰⴼⴻⵙⵏⴰⵅⵜ tafesnaxt “carrot” (from Latin pastinaca “parnsip, stingray”), ⵢⴻⵏⵏⴰⵢⴻⵔ yennayer “January; first month of the Berber New Year” (from Latin ianuarius), inter alia.

Berber is the substrate language for the Arabic varieties spoken in the Maghreb. Nonetheless, it has left few lexical borrowings in Arabic varieties, with the most notable exception of toponyms. The overwhelming majority of place names in Morocco are of Berber origin, e.g. ⴰⵎⵓⵔ ⵏ ⴰⴽⵓⵛ amur n akush “Land of God”, whence Marrakesh and Morocco; ⵉⵎⵉ ⵏ ⵜⴰⵏⵓⵜ imi n tanout “mouth of a small well”, ⵉⴼⵔⴰⵏ ifran “caves”; ⴰⵎⴽⵏⴰⵙ amknas whence Meknes “the Miknasa Zenata Berber tribe”; ⵜⵉⵟⵟⴰⵡⴰⵏ tiṭṭawan “springs” (with the Ghomara Berber feminine plural suffix ⴰⵏ –an) whence Tetouane; ⵜⵉⵏⴳⵉ tingi “marsh”, whence Tangier; ⵡⵔ ⴰⵣⵣⴰⵣⴰⵜ ur azzazat “without clamor; silent” whence Ouarzatate, etc.

Other ancient local words may include ݣناوة gnāwa “Sub-Saharan Africans and their musical repertoire in Morocco; a caste of largely endogamous black Africans living among both Arabophones and Berberophones”, probably from a Shilha gloss ⴰⴳⵏⴰⵡ agnaw “deaf-mute” (pl. ⵉⴳⵏⴰⵡⵏ ignawen) and later “black people” (semantic development resembles Arabic عجم ‘ajam “confusing or unclear way of speaking” → “Persians”). This word is probably also the origin of “Guinea” and perhaps “Djenné”.

In the domestic and culinary spheres, there exist a few important loanwords: كسكسو ksksu “couscous” from Berber ⵙⴻⴽⵙⵓ seksu; ساروت sārūt “key”, from Central Atlas Berber ⵜⴰⵙⴰⵔⵓⵜ tasarut; and صيفط ṣīfṭ “to send” (cf. Kabyle ⵙⵙⵉⴼⴻⴹ ssifeḍ). Some local flora and fauna have also retained their Berber names: زايس zāyis “octopus” from Berber ⴰⵣⴰⵢⵣ azayz; مشّ mušš “cat” (cf. Central Atlas Tamazight ⴰⵎⵓⵛⵛ amušš); لالة Lalla “lady; respected woman”, (related to Central Atlas Berber ⴰⵍⴰⵍⵍⵓ alallu “dignity”, from ⵜⵉⵍⴻⵍⵍⵉ tilelli “freedom”); دشار dšār from ⴷⵛⴰⵔ dšar “region”; شلاغم šlāḡem “mustache” from Berber ⴰⵛⵍⵖⵓⵎ ašlɣum.

It is possible that the use of feminine gender language names in Darija is Berber substrate: الريفية al-rifiyya “Riffian language”, cf. ⵜⴰⵔⵉⴼⵉⵜ Tarifit “Riffian language”. Additionally, Moroccan Darija exhibits a preference for broken plurals, particularly for ethnonyms or nationalities endemic to the region. By contrast, geographically distant peoples use the regular jarr plurals: مغاربة mġārba “Moroccans” (cf. Modern Standard Arabic مغربيين maġrebiyiin “Moroccans”) , تونسة twansa “Tunisians”, فواسة fwāsa “Fessis”, ريافة riyāfa “Riffians”, شلوح šluḥ “Shilha Berbers”, سواسة swāsa “people from the Souss region; frequently used synonymously with Shilha Berbers”, جبالة jbāla “Jbelis”, but مصريين maṣriyiin “Egyptians”, عراقيين erāqiyiin “Iraqis”, etc. It is interesting that Berber too uses complex and apophonic broken plural formations, like other Afro-Asiatic branches: ⴰⵎⵖⵔⵉⴱⵉ amɣribi → ⵉⵎⵖⵔⴰⴱⵉⵢⵏ imɣrabiyen “Moroccans”; ⴰⵛⵍⵃⵉ ašllḥi → ⵉⵛⵍⵃⵉⵢⵏ išlḥiyen “Shilha Berbers”, ⴰⴳⵍⵍⵉⴷ agllid “king” → ⵉⴳⵍⴷⴰⵏ igldan “kings”; ⵜⴰⴳⵍⴷⵉⵜ tagldit kingdom → ⵜⵉⴳⵍⴷⵉⵏ tigldin “kingdoms”.