Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This article surveys medieval church forms in historical Armenia and examines the role of Trdat the Architect in appropriating vocabulary from Armenia’s own remote past.

The church of the Holy Cross (Sourb Khach Yekeghetsi) on Aghtamar Island, Lake Van, Turkey. Aghtamar was once the capital city of the Armenian Kingdom of Vaspurakan, which was ruled by the Artsruni noble family. This church served as the seat of an Armenian Catholicosate for nearly 800 years, between 1116 and 1895 A.D, before it was dissolved and abandoned in the aftermath of the Hamidian Massacres against the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian population.

Introduction

The Armenian architectural tradition is distinguished by its conservation of a particular visual quality throughout the ages while simultaneously internalizing foreign influences from both East and West. But despite the timeless persistence of a uniquely Armenian aesthetic, the repository is not a monolith. Greek, Roman, Iranian, Muslim, and later Mongol sovereignty over the Armenian Highland left appreciable imprints on the visual vocabulary of both architecture and art. And whilst new, foreign pages were being added to the growing compendium of Armenian forms, indigenous architects were also drawing inspiration from the familiar pages of their own past; particularly, from well-known precedents scattered throughout Anatolia and the Caucasus that presumably remained operative in the social memory of the Armenian people. We can observe this tendency in a slew of 10th and 11th century Armenian churches that were unmistakably inspired by the earlier 7th century repository. That is, Armenian church architecture of the 10th and 11th centuries is marked by revival and appropriation of 7th century forms—the culmination of which took place under the architect Trdat, whose patent style infused centuries-old church plans with refined architectural details, an array of new local elements, as well as foreign borrowings.

Ruins of the medieval city of Ani, the capital of the Armenian Bagratuni Kingdom, now in modern-day Turkey. Known as “the city of 1001 churches”, Ani once represented the pinnacle of Armenian architectural feats and material art. The city was sacked by Mongols, Turks, Persians, Georgians, and Arabs, and experienced a number of earthquakes before being abandoned by the end of the 16th century. Top: Ruins of Ani; Second row left: Cathedral of Ani and Church of Christ the Redeemer; Second row right: Cathedral of Ani, apse; Third row left: Church of the Apostles, south narthex (added 13th century); Third row right: Chapel of St. Gregory of Shushan Pahlevuni; Fourth row left: Monastery of the Hripsimian Virgins; Fourth row right: Church of St. Gregory of Tigran Honents

Renowned seventh century structures such as Zvartnots Cathedral at Vagharshapat and Mren Church came to inform the 9th and 10th century forms of Ani Cathedral and Gagkashen, as well as a number of other structure including Aghtamar, Haghpat, and Sanahin. Most importantly however, the fundamental forms and layouts of these churches were incorporated into the ever-shifting socio-political landscape of historical Armenia. But these two churches were certainly not alone in the compendium of 7th century churches. For example, the Church of Hripsime at Echmiadzin also served as a “mother church” or archetype of sorts, in turn inspiring an array of the 10th and 11th century replications throughout historical Armenia. The basic interior and exterior themes of Hripsime reappear at several sites throughout historical Armenia centuries after its construction, including at the Monastery of Haghpat and Church of the Holy Cross at Aghtamar, the 10th century capital of the Artrsuni Kingdom of Vaspurakan. Aside from the prominent example of Hripsime, other 7th century church forms were also revived and appropriated, such as the 7th century Church of Irind and the 11th century Church of the Redeemer at Ani.

The monastery of Sanahin (left) and its gavit (right), 10th century, Lori province, Armenia. Gavit (Armenian: zhamatun), the distinctive Armenian style of narthex, came to serve as the entrance, mausoleum, and assembly room of many churches throughout Caucasus.

Aspects of Armenian Church Architecture

Pre-Christian Armenia stood at the crossroads of the ancient urban civilizations of the Near East and Greece. At the fall of Urartu in the 6th century B.C., Armenia became a satrapy to the Achaemenid Persian Empire under the so-called Yervandid rulers. For a period of nearly eight hundred years, Zoroastrianism was the dominant religion among the Armenian people, who began to incorporate elite visual vocabulary from the fallen Urartu, Persia and the civilizations of the Fertile Crescent into their own material productions. The Armenian pantheon developed around three Irano-Zoroastrian figures: Anahit (Avestan: Anahita), Aramazd (Avestan: Ahura Mazda) and Vahagn (Avestan: Verethragna), with a minority of Mithraists (Avestan: Mithra), and remained operative until the arrival of Christianity. Following Alexander’s conquest and the foundation of the Hellenistic Diadochi empires, the late Yervandids and later Artaxiads turned their gaze to the classical Greek world for artistic inspiration. In the first century A.D., the Artaxiad King Tigran the Great created an Armenian empire that spanned from the Mediterranean to the shores of the Caspian and Black Seas, only to be plundered by the Romans and consummated by Nero’s coronation of a new king, Trdat, in the Roman Forum.

Tigran the Great’s Empire; the Kingdom of Armenia at its greatest extent in history in the 1st century B.C. Tigran belonged to the Hellenophilic Artaxiad dynasty of Armenia, which had elevated the Greek language to the official language of their court. His capital Tigranakert (Latin: Tigranocerta) was sacked and plundered by the Romans, and the city was desecrated and razed to the ground.

Armenia was evangelized in the 3rd century A.D. by Thaddeus and Bartholomew, two of Christ’s disciples from Syria, although the national folk conversion story is an anecdote featuring two Roman women Hripsime and Gayane and a certain “Gregory the Illuminator” (Grigor Lusavorich) who saves the King Trdat from his doom as a spell-bound pig. But Christianity was not unanimously accepted by the Armenian nobles (nakharars) at first; many families, including the Artsrunis and the Arshakunis, refused to renounce their Zoroastrian creed and allegiance to Sassanian Persia. But following his father’s major defeat at Avarayr, Vahan Mamikonian signed the Treaty of Nvasarak with the Sassanian King Vologases (Balash) and secured freedom of worship for the newly Christianized Armenia. In 301 A.D., Armenia became the first state apparatus to make Christianity its official religion.

Khor Virap monastery (Armenia) nestled on the foothills of Mount Ararat (Turkey). Khor Virap, literally “deep well,” is the site where, according to the national Christianization anecdote, King Trdat had Gregory the Illuminator imprisoned in a pit. During a hunt, Trdat suddenly turned into a pig, and had to recruit the help of the outcasted Gregory to release him from his affliction. As a token of gratitude, the King converted to Christianity and built churches throughout Armenia. Note the Armenian folk conversion tradition of Gregory, the patron saint of Armenia, bares inextricable parallels to the Georgian conversion tradition of Nino, the patron saint of Georgia.

Early Christian buildings in Armenia were basilicas, such at that at Aghts’k’, which were longitudinal, aisled buildings that were cheap to build and could accommodate a growing Christian population within its walls. The 4th century Tsiranavor Basilica at Artashat is covered by a barrel vault, a sort of 3-D arch, which was distinct from the basilicas of the Roman world that were normally covered by timber vaults. Another distinct feature of Armenian and Georgian churches is the use of rubble masonry, which calls for cleanly cut, polish facing stones filled with fieldstone, rubble, and mortar. This sort of material is not only economical but also lightens the superstructure of the building, allowing for heightened verticality, and smooth curves. Contrarily, the fifth century churches of Syria such as that of Qalb Lozeh are almost exclusively solid stone masonry, or ashlar masonry.

Qalb Lozeh Basilica, 5th century, Syria. Early Syrian Churches employed solid stone masonry, or ashlar masonry, while Armenian and Georgian churches almost exclusively employed rubble masonry, which is more affordable, easier to use, and allows for a lighter superstructure and curvature.

The last and most distinct feature of early Armenian churches are steles and later khachkars that appear on ecclesiastical grounds outside of the main church structure. This suggests outdoor worship, which would have been highly unusual in the early Christian world and may be an appropriation of pre-Christian, Urartian rituals that were still operative in the social memory of the inhabitants of the Armenian highland.

Odzun Church, 7th century, Armenia. Outside the church is a raised arch form with stairs leading to two steles sculpted on all four faces, featuring stories from the Old Testament, images of saints, military saints, King Trdat with a pig head (from the folk conversion story), and a relief of the tomb of Hripsime with a ladder. This form suggests some kind of outdoor worship, perhaps an heirloom of Urartian culture, and was nonetheless highly unusual in the early Christian world.

Trdat the Architect

The Armenian architect Trdat earned unusual celebrity from his high-level projects in the Caucasus and the Byzantine world, and as such he is one of the few medieval architects mentioned by name in contemporary sources. Trdat was entrusted with the construction of cathedrals, chapels, and monasteries at sites such as Ani, Haghpat, and Sanahin at the turn of the 11th century. Here it is important to note the unique identity of medieval Armenia, which was not only linked to the Mediterranean but also to the Islamic world, and possessed a language and form of Christianity distinct from its Byzantine overlords. The architect Trdat thus served as a cultural ambassador of sorts—responsible for both introducing new styles from Byzantium as well as preserving traditional Armenian forms in his buildings. He is also renowned for experimenting with new plans and styles, which is evident at sites such as Haghpat and Sanahin. But Trdat’s work was not limited to Armenia and Armenian patrons—it was the same Trdat who was entrusted with refurbishing the Hagia Sofia church in Constantinople following a devastating earthquake that led to the collapse of its dome in 989 A.D. Although the details surrounding Trdat’s Constantinopolitan commission remain unclear, eminence attained from his high-level projects in the Caucasus must have played a primal role in securing his candidacy.

Interior of Hagia Sophia Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey. Originally a Greek Orthodox patriarchal basilica constructed by the Byzantines in the 6th century A.D., the dome collapsed at the end of the 10th century and Trdat the Architect (Trdat Chartarapet) from Armenia was entrusted with its refurbishing. According to John Scylitzes, the scaffolding alone costed one thousand pounds of gold. It would be interesting to know how Trdat earned such a prestigious commission, as one can imagine hiring a local architect would have been more practical.

Zvartnots Cathedral and the Church of Gagik

Zvartnots Church, the patriarchal resident of Nerses III (640-661 A.D.). The setting in the landscape of the church must have been deliberately aligned with Mount Ararat. The Ionic capitals of the exedrae are engraved with the framed circular monogram “Narsou” (“of Nerses”) in Greek.

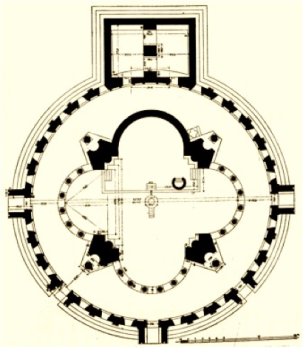

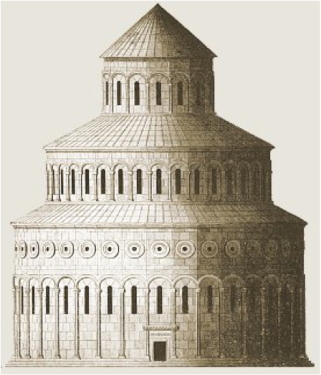

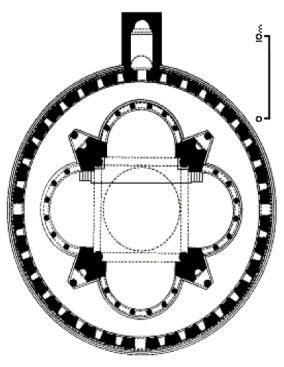

Perhaps one of the most outspoken examples of the medieval revival can be observed in the comparison between the 7th century Zvartnots Church near Echmiadzin and the 11th century Gagkashen Cathedral at Ani, which was constructed by Trdat. Both of the churches feature aisled tetraconch plans, with four large, W-shaped piers and exedrae comprised of six columns. Both structures feature stylobates and both were built employing rubble masonry, which was typical of Armenian churches as opposed to ashlar masonry in Syrian churches. Zvartnots is the largest aisled tetraconch in the Caucasus, and it lies within an extensive patriarchal or Episcopal palace complex. Most scholars agree on the rotunda plan of Zvartnots, with arched windows and a ring of oculi. What is most important in analyzing Zvartnots is understanding the socio-political context of its founding. The 7th century A.D. witnessed a cosmic confrontation of two age-old foes: the Byzantines and the Sassanid Persians. From a Christological standpoint, the Armenians condemned the doctrine of Monophysitism, but also rejected the Orthodox doctrine of the Byzantines, which professed the duality of Christ’s nature, as proclaimed by the fourth ecumenical council at Chalcedon in 451 AD. But the geographical location of Zvartnots in the Byzantine Empire adjacent to the Sassanian border thus necessitated the development of a sort of “cultural allegiance” to Constantinople, which manifested itself in the form of visual vocabulary in architectural forms. In this vain, the local leader Nerses III had in fact religiously aligned himself with the Byzantines. This motivation in turn allowed for the transmission of a number of architectural innovations from a Byzantine milieu into Armenian Church architecture, as evidenced by the church of Zvartnots. The first is the use of columns and exedrae in the interior of the church, which is evident in Byzantine churches in western Anatolia, a prominent example of which is the Hagia Sofia. The columns composing the exedrae at Zvartnots are of the Ionic order, however they have been “Armenized” by the use of local knot motifs in a fashion similar to the Dvin “Ionic” capital from the 5th-6th centuries. Nerses III’s deliberate choice to affiliate with the Byzantine world is perhaps best evinced by the use of Byzantine cross monograms with a Greek inscription that reads “Of Nerses”. The eagle images are also appropriated from a Byzantine milieu, where the bird is a symbol of power and divinity. While the Greek monograms themselves are symbols associated with an era of Greek dominance in the politics of historical Armenia, the layout and architectural concept of the church itself as a multi-level rotunda with an interior tetraconch design became a timeless standard in the Armenian repository that was actively drawn upon for centuries to come.

Gagik’s Church (Gagkashen) at Ani, 1001-6 A.D. The columns of the exedrae at Gagkashen are also of the Ionic order, but do not feature Greek monograms like those at the Zvartnots cathedral four centuries before.

The Church of Gagik (Gagkashen) at Ani, built 1001-6 A.D. by the architect Trdat, appears to be a stylistic imitation of the church of Zvarnots. This observation did not escape the attention of the medieval Armenian chronicler Stepanos of Taron, who most aptly noted: “Gagik, King of Armenia, was taken with the idea of building in the city of Ani a church similar in size and plan to the great church at Vagharshapat, dedicated to St. Gregory, which was then in ruins.” As Stepanos relates, Zvartnots lay in ruins at the time of the construction of Gagkashen, which casts a degree of mystery on Trdat’s ability to produce a strikingly similar plan and layout at Gagkashen. The church follows a rotunda plan with an aisled tetraconch and columnar exedrae. However the diameter of the central shell at Gagkashen is markedly larger than that at Zvartnots, which in turn makes for a more spacious interior and less-pronounced ambulatory surrounding the tetraconch. In addition, Gagkashen only has three entrances, while Zvartnots has five. Both Gagkashen and Zvartnots feature sculpted colonnettes and oculi on the exterior, ground segment of the churches, although Gagkashen is a true rotunda while Zvarnots is comprised of thirty-two sides on the bottom two segments and sixteen on the drum. Gagkashen also employs Ionic columns, however they conspicuously lack the Greek monograms found on the columns at Zvartnots. This of course is relevant to the contemporary socio-political context of Gagkashen’s construction; namely, while Zvartnots was commissioned by a pro-Byzantine (or simply Hellenophilic) patron during the era of Greek dominance in Armenia, Gagkashen was constructed during the Bagratuni suzerainty under the Abbasid Caliphs, when Armenia was a contested territory between the Muslims and Byzantines. The incidence of distinctly Greek visual vocabulary in buildings at Ani is thus less pronounced, as Trdat constructed the church in a period of relative Armenian autonomy in the region between two warring empires. In addition, the colonnettes of the four piers at Gagkashen project more emphatically than at Zvartnots, creating a greater sense of linearity. Trdat also replaced the solid eastern apse at Zvartnots with a fourth exedra at Gagkashen that is open to the ambulatory. Altogether, the Church of Gagik outlines two prominent features of Trdat’s architectural aesthetic: linearity created by profiling of supported arches, and enlarged central spaces. These elements would also be incorporated into other structures built by Trdat in imitation of 7th century forms.

The Church of Mren and the Cathedral of Ani

Mren Church, 7th century, located by a river gorge at the border of modern-day Turkey with Armenia. Distinguished by its rose-colored stones, painting in the interior of Mren does not survive due to the smoothness of masonry. Regrettably, there is a large crack at the northwest facade, and the building is collapsing.

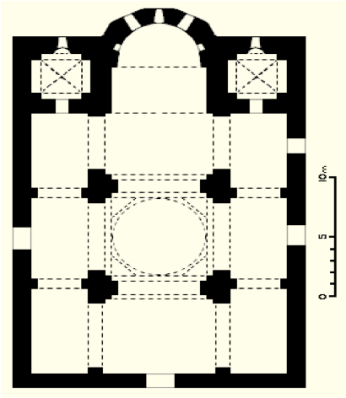

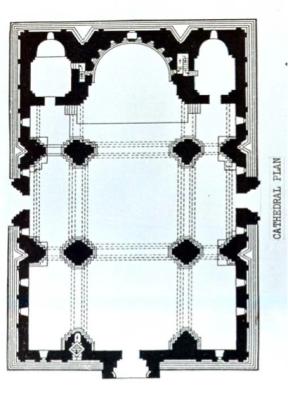

Another prominent example of architectural revival can be observed in the 7th century Church of Mren and the 10th century Cathedral of Ani. Considering the geographical proximity of the two sites, the stylistic resemblance of the two churches is not difficult to surmise. Mren follows a domed basilica plan, which was common among religious structures of the early Christian period throughout the Near East and Europe as for accommodating a growing Christian population. The interior of the church is divided into aisles that lead to two side chambers adjacent to the apse, which is projecting outwards on the exterior of the structure. The centralized dome is supported by piers, and the structure employs rubble masonry featuring a geometric exterior with a faceted drum and conical roof. Of note, the dome is held up by squinches, which was an Iranian innovation and was employed much more commonly in Armenia during the earlier centuries of Christianity before the widespread adoption of European pendentives.

Mren features an exquisite array of exterior sculpture, which is a feature characteristic of Armenian Church architecture in comparison to other styles from around the Christian world. The west façade features an inscription depicting the return of the Holy Cross to Jerusalem from the Sassanian capital, Ctesiphon, by the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius in 630 A.D. The inclusion of this scene is revealing of the strong network of alliances that existed between Byzantium and Armenian princes. The portal under the inscription is also sculpted, including depictions of angels, which demonstrates Byzantine influence at frontier regions such as Mren. Another exterior sculpture is that depicting Christ, Peter, Paul, the appointed imperial official Davit Saharuni, and the local imperial official Nerses Kamsarakan. This inscription seems to be informed by an Iranian milieu, particularly in the style of dress of the local figures Davit and Nerseh, who are wearing Persian riding coats. This observation is consistent with the many centuries of Iranian sovereignty over Armenia preceding the Byzantine conquest of the region, and validates the importation of Iranian styles of raiment and vocabulary of political legitimacy in an architectural context. Altogether, the content and vocabulary of the exterior sculpture at Mren demonstrates the interaction of Armenians with foreign powers at the frontier. And while these depictions vary depending on the contemporary political allegiances of Armenia, the tradition of exterior sculpture would become part of the architectural canon of Armenian churches and would inform the design of churches for many centuries to come.

The Mother Cathedral of Ani, 10th century, at Ani in modern day Turkey. Stylistic resemblances between the churches at Ani and Gothic architecture in Europe such as the church abbey of St. Denis have raised questions regarding the origin of that architectural order. In orientalist fashion, the German traveller Karl Schnaase (1884) remarks that the interior of the Cathedral of Ani must have been built by a European master builder, an observation which nonetheless speaks to the uncanny resemblance between the two styles.

The Cathedral of Ani is one such church that seems to have appropriated many components of Mren but in a 10th and 11th century context. Ani Cathedral was constructed by Trdat the Architect, to whom the Church of Gagik in the same city has also been attributed, as discussed above. The cathedral itself was commissioned by another regal patron, King Smbat II, although according to an inscription on the church, construction was interrupted by the the King’s death in 989 and later resumed by Queen Katramide the Georgian. Like the church of Mren, the Cathedral of Ani follows a domed basilica plan, and it once supported a dome with a conical roof held up by pendentives. The whole structure including the apse is inscribed in a rectangle, while the apse is projecting at Mren. Much like Mren, the interior is divided into three aisles by four large, freestanding piers. The church also features exterior niches and a stylobate. However, in contrast to Mren, Ani Cathedral has narrower side aisles caused by closer placement of the piers to the lateral wall, which in turn enlarges the central space. As discussed, this was an innovation Trdat also employed at Gagkashen. Another departure from 7th century architecture was Trdat’s use of pendentives instead of squinches to support the central dome, which was probably imported from a Byzantine milieu from structures such as the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Thus while Ani Cathedral drew heavily from the layout of Mren, it also appropriated many contemporary elements of architectural design that were associated with the ruling class of 10th and 11th century Armenia.

”

”

Scale of the Cathedral of Ani, 10th century, west entrance. The dome is supported by pendentives (a European innovation, as opposed to Iranian squinches found at Mren) held up by slightly pointed 3-ribbed arches supported on bundled shafts that spring from profiled piers, in effect giving the interior a strikingly muscular effect and an emphasis on linearity.

Ani Cathedral is distinguished by its appropriation of exterior sculpture in the contemporary context of the city of Ani. Namely, the entire masonry skin is united by sculpted colonettes and arches, and this became a feature of many Armenian churches in the 10th and 11th centuries. The vaulting of the cathedral is supported by slightly pointed rib-arches that spring from profiled piers, which bear the structural advantage of supporting more load, and adds to the verticality of the structure while affording a greater sense of “linearity” from a stylistic point of view. In addition, the steps of the arches “bind” with the ribbed piers, creating a more integrated interior design. Altogether, the Cathedral of Ani represents a refinement of interior vocabulary used at Mren, in that it takes rudimentary profiling and incorporates it into an aesthetic. These developments are not only telling of continued appropriation of elements from a Byzantine milieu, but also of the masterfulness of Trdat the Architect as a reviser of the simpler forms from the 7th century.

Sources

Maranci, Christina. “Building Churches in Armenia: Art at the Borders of Empire and the Edge of Canon.” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 88, No. 4 (Dec., 2006), pp. 656-675

Maranci, Christina. “Byzantium through Armenian Eyes: Cultural Appropriation and the Church of Zuart’noc’.” Gesta. International Center of Medieval Art: 2001. pp. 105-124.

Maranci, Christina. “The Architect Trdat: Building Practices and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Byzantium and Armenia”. The Journal of the Society of architectural historians, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Sep., 2003), pp. 294-305.