Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. The goal of this article is to familiarize the reader with the Iranian origins, history, and language of the Hui community of China.

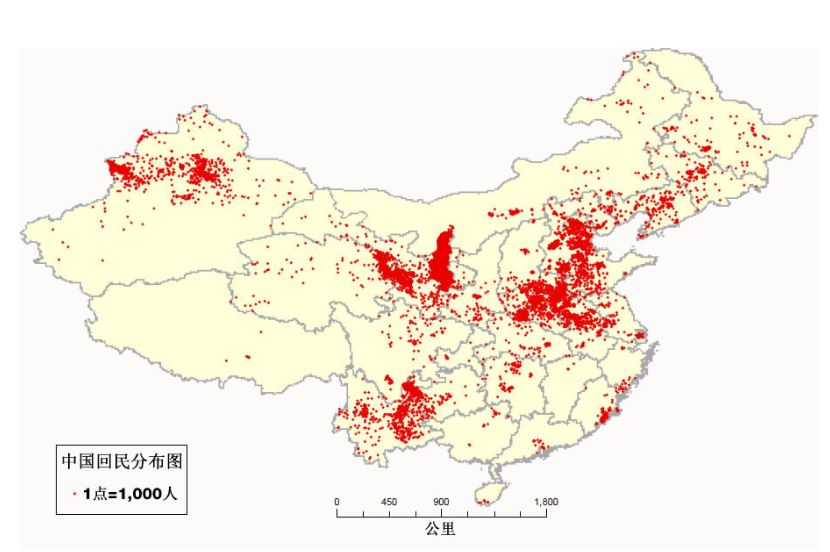

At greater than 10.5 million souls, the Hui people (回族 huí zú) compose the largest Muslim community and second largest “ethnic minority” in the People’s Republic of China. The Hui are the descendants of 13th century Persian-speakers who were deported thither following the Mongol conquest of Persia, Transoxiana, Khurāsān, and Khwārezm (the eponymous 回回國 huíhuí guó first referenced in a Ming Dynasty translation of the Mongolian chronicle 蒙古秘史 The Secret History of the Mongols). This means that after the Han Chinese (~1.3 billion) and the Zhuang (~18 million; whose homeland lies in the remote mountains bordering Vietnam), the descendants of Persian immigrants are the third largest ethnic community in China and are distributed broadly in nearly all of her major urban centers. Despite their importance, little international media attention has been devoted to their existence, perhaps due to the precarious conditions faced by smaller minorities such as Tibetans and Uyghurs in the country’s peripheries.

Much effort has been undertaken through the use of deliberately ambiguous language and, in some cases, pseudoscientific acrobatics, to assign Arab, Turkic, and even Indic identity to the ancestors of the Hui, but these attempts have fallen short of providing any compelling evidence towards those ends. The extant inscriptions and texts throughout China, Hui dialectical data as well as official Chinese dynastic accounts reveal without ambiguity that the Hui were originally a monolingual Persian-speaking community whose domestic, communal, and even spiritual life was conducted in Persian, while their Islamic faith necessitated knowledge of Arabic for access to their liturgy.

The Persian Muslims’ deportation to China was not in isolation, as they were originally accompanied in great numbers by Persian Jews (主鶻回回 zhǔhú huíhuí “Jewish Huihui”; zhǔhú being a phonetic transliteration of colloquial Persian جهود juhūd “Jew”) whom they had lived alongside in their homeland, and whose descendants are today referred to in loose terms as “Kaifeng Jews” (開封猶太族; Kāifēng Yóutàizú). Both of these groups preserved vernacular Persian for hundreds of years in diaspora, but were eventually faced with targeted assimilation pressures under the ensuing Ming dynasty (1368–1644) that resulted in their shift to local Chinese languages. Thereafter, for obvious reasons Arabic and Aramaic/Hebrew retained their currency as vital instruments in religious life, but Persian enjoyed a robust status in the arenas of both secular and religious literature, sermons, poetry, social institutions and diplomacy among Hui Muslims, Jews, and even the Chinese administration (discussed below). Today, the Persian language remains an important fixture in the Hui Muslim and Chinese Jewish identities. The Hui have even retained the endonym for the language of their forefathers, 发热西 Fārèxī (lit. “fever west”, a phonetic transliteration of فارسى fârsi) in a manner not dissimilar to the dissemination of the word “Farsi” in lieu of “Persian” by 20th century Iranian immigrants to the Occident–while standard Mandarin uses the historic Chinese allonym 波斯语 Bōsī yǔ “language of Persia”, from 波斯 Bōsī “Persia” first attested in the The Book of [Northern] Wei (Wèi-shū 魏書; composed in 551-54 AD).

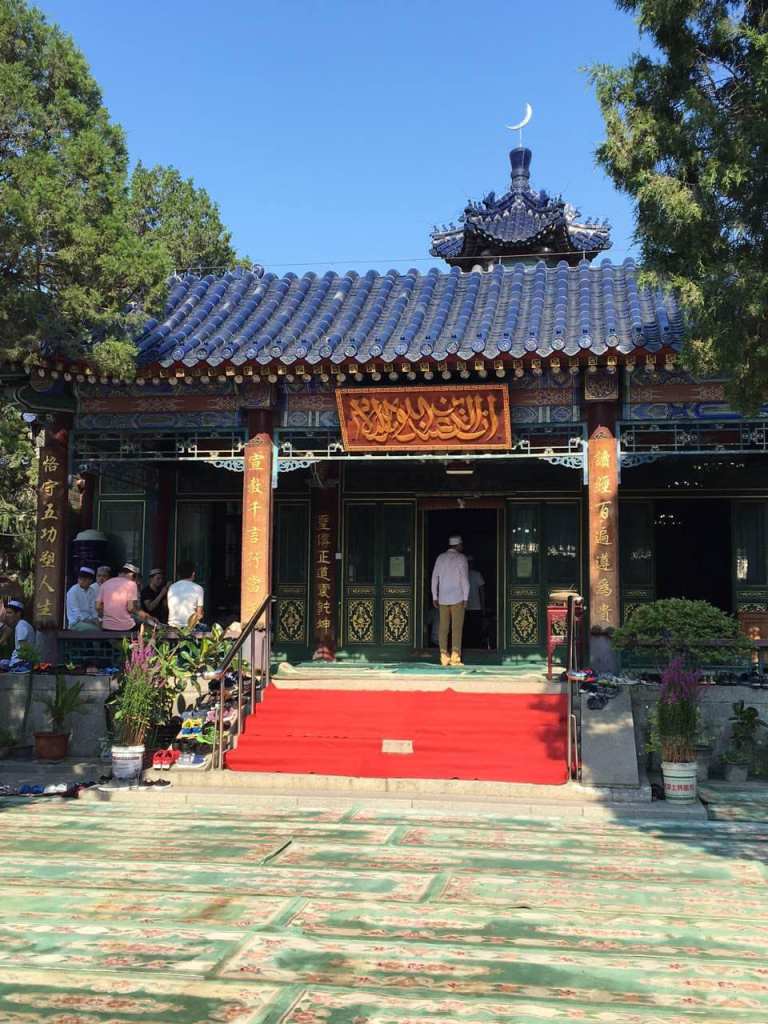

The gravestones of two founding Imams (ahōng 啊訇، from Persian âkhond آخوند “imam”) with the nisbahs البخارى al-Bukhārī and القزوينى al-Qazwīnī، revealing their places of origin, are interred here. Beijing’s Ox Street Mosque also includes a commemoratory stele erected at the end of the 15th century in Mandarin and Persian. (2017, photos by Afsheen Sharifzadeh)

On the Origins of the Hui

Insofar as it is possible to generalize about the origins of all the people in China who are classified as Hui, it seem likely that “the origins of most of them are in the thousands of mainly Persian speaking Central Asian Muslims recruited or conscripted by the Mongol armies which took control of China in the thirteenth century” (Dillon, p. 156). This fact at first seems unbewildering, since at its acme the Mongol Horde did not succeed in conquering India, the core of the Arabic-speaking world, Southeast Asia, Byzantium, or any “European” society west of Kievan Rus. The roughly contiguous Chinese and Iranian ecumenes (the Sinosphere 汉字文化圈 and Persosphere ايران بزرگ “Greater Iran; Iranian World”) were the two chief sophisticated urban civilizations that the Mongols succeeded in subjugating, and whose cultures were sufficiently advanced enough to be adopted wholesale by their conquerors (the Golden Horde lived in proximity to, but not among, the eastern Slavs). The popular depictions of plunder, destruction and massacre wrought by Chingis Khan–borne primarily from coeval Persian and Christian missionary sources–are in fact almost exclusively referring to Greater Iranian cities. After all, it was under the pretext of revenge for the Khwārazmshāh‘s execution of a Mongol merchant convoy at Otrār (فاراب Fārāb) that Chingis Khan chose to invade Central Asia and Persia. Minhāj al-Sirāj Juzjānī, a 13th century Persian historian who authored a synchronic commentary on the Mongol conquest of the Khwarezmian Empire from the safety of his refuge in Delhi, laments:

Alas, how much Muslim blood was spilled because of that murder! From all sides poured torrents of pure blood, and this movement of anger brought about the ruin and depopulation of the earth. (55 Levi, 2010, p. 127.)

Chief among the contemporaneous Persian sources is the account of another historian and later Mongol state official, Atā-Malek Juvayni, entitled “History of the World Conqueror” (تاریخ جهانگشای Tārīkh-i Jahān-gushāy; c. 1260 AD). Indeed, Juvayni writes that after the fall of Samarkand and the massacring of its inhabitants,

…the people who had escaped from beneath the sword were numbered; 30,000 of them were chosen for their craftsmanship, and these [Chinggis Khan] distributed among his sons and kinsmen, while the like number were selected from the youthful and valiant to form a levy.

As Huíhuí (referring to both Persian-speaking Muslims and Jews) spread throughout Yuan China, it was craftsman and artisans (工匠 gōngjiàng) who were most prominent after conscripted troops:

Many of the more than 30,000 craftsmen captured by Chinggis Khan’s forces in the 1220 Samarkand campaign, were specialists in delicate work who were enlisted in the official government crafts bureau, the guanju. This might include producing Central Asian style brocades or silks or the manufacture of cannons. All the artisans brought to China by the Mongols were pressed into the official quasi-military system under which the Yuan dynasty employed craftsmen and were not permitted to operate privately. (Dillon, Michael. China’s Muslim Hui Community, p. 23)

Juvayni provides similar accounts of the odious fate that befell the people of Bukhārā, Merv, Nisā, Kāth, Gurganj, Termez, Balkh, Nishāpur, Tūs, Herāt and other major urban centers in the medieval Iranian World. For example, following the conquest of Gurganj, the capital of Khwārezm, Juvayni relates that artisans and others with valuable skills such as merchants, scholars and physicians–said to number over 100,000 (certainly hyperbole)–were separated from the rest and deported to China where they lived in diaspora:

‘To be brief, when the Mongols had ended the battle of Khorazm and had done with leading captive, plundering, slaughter and bloodshed, such of the inhabitants as were artisans were divided up and sent to the countries of the East [China and Mongolia]. Today there are many places in these parts that are cultivated and peopled by the inhabitants of Khorazm’ (Juvayni/Boyle 1952) p. 128

Notably, the en masse deportation of Huíhuí artisans from conquered territories in Central Asia is corroborated multiple times in the Secret History of the Mongols (蒙古秘史 Ménggǔ mìshǐ) as well as the official dynastic history of Mongol rule in China (Yuán Shǐ 元史; c. 1370 AD):

‘Hasana, a Kerait, transported 3,000 Huihui artisans from Samarkand and Bukhara and other places and put them in Xunmalin [near Kalgan/Zhangjiakou] in the reign of Ogedei.’ (Yuanshi 122; Leslie (1986) p. 79.

‘In the Yuan period, the Hui-hui (from Samarkand) spread over the whole of China. By the Yuan dynasty the Muslims had extended to the four corners [of the country], all preserving their religion without change.’ (Mingshi 332; Leslie (1986) p.79)

In the following centuries, Chinese sources make mention of prominent Persian Muslims and Jews in the administrative and mercantile spheres of Chinese society. Many of these individuals hailed from the primary Huíhuí cadre which had been conscripted and deported overland from Central Asia and Persia during the Mongol conquest of those regions. For example, the Persian Sayyed-e Ajall Šams-al-Dīn ʿOmar Boḵārī (d. 1279), a native of Bukhara, was appointed governor of Yunnan province by Qubilai Khan, and together with his son Nāṣer-al-Dīn was responsible for the spread of Islam in southern China (Persian: ماچين Māchīn “Greater China”; rarely منزى Manzī, from Chinese 蠻子 mánzi “southern barbarians; non-Sinicized southerner” > 南蠻 Nánmán via Mongolian). His great-great-great-grandson, the famous Iranian-Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, and fleet admiral Zhèng Hé 郑和 (born 马和 Mǎ Hé) commanded the largest and most advance fleet the world had ever seen to Java, Malacca, Siam, Ceylon, India, Persia, Arabia and the Horn of Africa during seven expeditions between 1405 to 1433. Zheng He presented gifts of silk, porcelain, gold, and silver, and China received such novelties as ostriches, zebras, camels, and ivory from the Swahili Coast in return. The giraffe that he brought back from Malindi was considered to be a 麒麟 qílín and taken as proof of the Mandate of Heaven (天命 tiānmìng) upon the administration.

While the Huíhuí nucleus (Muslim and Jewish Persian-speakers) was predominantly located in the northwest, center and southwest of China where they had been brought overland from Central Asia and Persia by the Mongols, by that period China had also established maritime contacts with merchants from the Persian Gulf, a limited number of whom were permitted to settle in port cities along the East China Sea. Chinese documents do not contain information on the ethnic origins of officials in the foreign quarters of the port of Zaiton (泉州 Quánzhōu; زيتون Zaytūn), however Ibn Baṭṭūṭa mentioned several prominent Persians: Kamāl-al-Dīn ʿAbd-Allāh Eṣfahānī, šayḵ-al-Eslām (dean of Muslim religious leaders) from Isfahan; Tāj-al-Dīn Ardawīlī, qāżi’l-Moslemīn (Muslim judge) from Ardabil; the prosperous merchant Šaraf-al-Dīn Tabrīzī of Tabriz; and Borhān-al-Dīn Kāzerūnī of Kazerun, a shaikh of the Sufi Kāzarūnīya order. While smaller in number, there was also mention of a community of Arabian merchants in Quanzhou that had arrived along the same maritime route as the Persians. Notably, it was through the Persians that the Chinese had first come to know of Arabia and the Arabs (大食 Dà-shí “Arab” < Persian تازى Tāzī “Arab”, referring to Arabs of the tribe of طي Ṭaī). The presence of Arabian merchants in a limited number of port cities where Persian-speakers still seem to have constituted a plurality and oligarchy among Muslims–compounded by the facts that the two coreligionists are usually not differentiated in Chinese historical documents and that Arabic is the liturgical language of both people–has lent false credence to a popular claim among those eager to influence China’s Muslims that the Hui are predominantly descendants of (1) Arabs, (2) Turks or, the deliberately ambiguous option, (3) an unknowable mixture of peoples.

The Hui Under the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties

The three officially recognized languages of Yuan administration and education were thus Chinese, Mongolian, and Persian; the terms 回回文 Huí-huí-wén (lit. “language of the hui-hui,” the term referring to Persian-speaking Muslims of Central Asia), 铺速蠻字 pù-sù-mán-zì (“Muslim language”, from Persian مسلمان musalmān), and 亦思替非文 yì-sī-tì-fēi-wén (“chosen language”, possibly < Ar. اصطفاء eṣṭefāʾ “choosing, selecting,” referring to the “chosen,” or “Islamic,” language; Yuan-shi LXXXVII, p. 2190; Huang, pp. 85-86) encountered in the documents of the period probably all refer to Persian (Chenheng, 2000 “Literature of Northwest China”; although it has been proposed that at least in some instances the third term refers to the language of the Qur’an). The Yuan administration opened a Persian language school called 回回國子學 Huíhuí guózi xué which is considered to the earliest foreign language school in China (Han Rulin, 1982; Fu Ke, 2004 “History of Chinese Foreign Teaching”).

During this period, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, who was visiting China in the mid-14th century, mentions the son of a Mongol khan who was especially fond of Persian singing; apparently on one occasion he ordered his court musicians to sing several times a poem by Saʿdī Shīrāzī, which had been set to music (ibn Baṭṭūṭa, tr. Mowaḥḥed, II, p. 750 n. 2). Ironically, Saʿdī (1210-1292 A.D.), who himself had been cast into a life of itineration by the Mongol invasions, could barely restrain himself from lamenting at the ruin wrought by Chingis Khan, likening the destruction of Samarkand to the Arabian destruction of the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon six centuries earlier. Apparently, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II even recited Saʿdī’s forlorn couplet as he ambulated through the decrepit Mega Palation of Constantinople two centuries thereafter in 1453:

پردهداری میکند در قصر قیصر عنکبوت; بوم نوبت میزند بر تارم افراسیاب

Parde-dāri mikonad dar qaṣr-e Qayṣar ankabūt; būm nowbat mizanad bar tāram-e Afrāsiāb

“The spider is curtain-bearer in the palace of Khosrow [Ctesiphon]; the owl calls the watch shifts in the towers of Afrasiab [Samarkand]”

(1) The prayer hall of the Ming-era Ox Street Mosque (牛街礼拜寺 Niú jiē lǐbàisì; c. 1443 AD), Beijing (2) Hui Muslims on the mosque grounds (3) Entrance to a gǒng-běi (拱北 – “a small Muslim shrine”, from Persian گنبد gonbad “dome”) (4) An incense burner (香爐 xiānglú) used by Muslims (5) the author inside Ox Street Mosque, Beijing (photos by Afsheen Sharifzadeh)

Under the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the Sì-yí-guǎn (四夷館, “Office for the four barbarian [nations]”) was established to train translators to provide official translations of books and diplomatic documents. Since Persian was one of the main diplomatic languages used by the Ming to communicate with Tibet, Ceylon, Cambodia, Champa, Java, Malacca, and the Timurid Empire, numerous Ming-era Persian language inscriptions have been discovered in these territories, including the trilingual Tibetan, Chinese and Persian language inscriptions at Tsurphu monastery in Tibet. The first Ming emperor, Tai-zu 太祖 (r. 1368-97), apparently ordered a group headed by Ma-sha-yi-hei (probably مشايخ Mašāyeḵ) to translate several Persian books, including one on astronomy, into Chinese, and in 1407 Ming Cheng-zu (r. 1403-25) issued an edict in Chinese, Mongolian, and Persian for the protection of Islamic minorities. Additionally the Huí-huí guǎn yì yǔ (回回館譯語 “Textbook for Translation from Huihui [Persian]”), compiled by the Sì-yí-guǎn, was a textbook for teachers and translators; one extant copy includes a Persian-Chinese vocabulary of 1,010 words. Other Chinese Muslim scholars of the Ming period who taught Persian, translated Persian works into Chinese, or integrated material from Persian works into their own books in Chinese were Chang Zhi-mei (1610-70) and Liu Zhi (ca. 1660-1730).

In the mid-16th century madrasas (schools of Islamic law, jīng táng 经堂, lit. “hall of doctrinal texts”) were established in China. Some Muslim scholars taught Islamic books in Persian in their homes and annotated both Arabic and Chinese texts with Persian, but, as time went on, it appears only Arabic was used in religious education, though in a few mosques there was instruction in both languages. Persian continued to be spoken and read among Muslims throughout the period, but by the end of the Ming period Chinese had become the primary spoken language among the Hui. However the Persian language was still taught in several Muslim schools that were established in the 1920s or later. Ha De-chen (1887-1943) and Wang Jing-zhai (1879-1948) were among the most noted Chinese translators from Persian under the National Republic of China. The latter translated Saʿdī’s Golestān گلستان as Zhēn-jìng huā-yuán 真境花园 (“Ethereal Garden”, published by Beijing Muslim Press, 1947).

Today, Beijing alone is home to at least 72 mosques, and visitors can encounter innumerable madrasas and perhaps dozens to hundreds of Hui restaurants with their idiosyncratic façades of crescent-shaped arches, serving traditional dishes such as 烤羊肉串 kǎo yángròu chuàn “grilled mutton kababs”, 手抓羊肉 shǒu zhuā yángròu “grabbing mutton”, and 馕 náng bread (from Persian نان nān).

Sayyed-e Ajall Šams-al-Dīn Boḵārī (Persian: سید اجل شمسالدین عمر بخاری; Chinese: 赛典赤·赡思丁 Sàidiǎnchì Zhānsīdīng; 1211–1279), a Persian from Bukhara, was appointed as Yunnan’s first provincial governor during the Yuan dynasty. His descendant, the celebrated Admiral Zheng He 郑和 commanded seven expeditionary treasure voyages to Java, Malacca, Siam, India, Persia, Arabia and the Horn of Africa from 1405 to 1433. The giraffe that he brought back from Malindi was considered to be a 麒麟 qílín and taken as proof of the Mandate of Heaven upon the administration

Hui Chinese Dialects

In the religious sphere, the Hui have inherited terminology from the Persian substrate of their forefathers, however Arabic terms derived from the Qur’an or their Chinese translations are also used today. For example, 木速蠻 mù-sù-mán “Muslim” (from Persian مسلمان mosalmān, first attested as 铺速蠻 pù-sù-mán in Yuan sources, meaning “Persian”; note 穆斯林 mù-sī-lín from Quranic Arabic muslim مسلم is also used today); 別安白爾 bié-ān-báiěr “prophet” (from Persian peyḡambar پيغمبر; cf. Arabic nabī نبي), the Persian term for the Prophet Moḥammad (first attested as 别安白尔皇帝 bié-ān-báiěr huángdì “Emperor prophet” in Xuanzong’s 赛氏总族牒 “Sai’s General Clan Sutra)”; 答失蛮 dá-shī-mán “learned man; scholar” (from Persian dānešmand دانشمند; cf. Arabic ‘ālim عالم); 迭里威士 dié-lǐ-wēi-shì “member of a Sufi order” (from Persian darvīš درويش); 乃瑪孜 nǎi-mǎ-zī “prayer” (from Persian namāz نماز; cf. Arabic ṣalāt صلاة); etc. Many of them (e.g., dá-shī-mán and bié-ān-bái-ěr) were also fashionable in the writings of non-Muslim Chinese literati. Words like 多災海 duō-zāi-hǎi “hell” (from Persian dūzaḵ دزاخ); (Mathews, nos. 6421, 6939, 2014) and 榜达 bǎng dá “morning” (from Persian bāmdād بامداد) are still common among Muslims in Beijing. In addition to incorporating a great many Persian words in their daily religious rituals, Beijing Muslims also hear sermons in Persian, and at evening prayer during the month of Ramażān they recite poems of praise in Persian (Yu Guang-zeng, p. 9).

Hui Muslim restaurants abound throughout China, particularly in Beijing and other historic Hui centers. The Hui are distinguished from the Han Chinese by their round skullcaps and headscarves (戴斯达尔 dài-sī-dá’ěr, from Persian dastâr دستار) , although only sported by some members of the community (Photos by Afsheen Sharifzadeh)

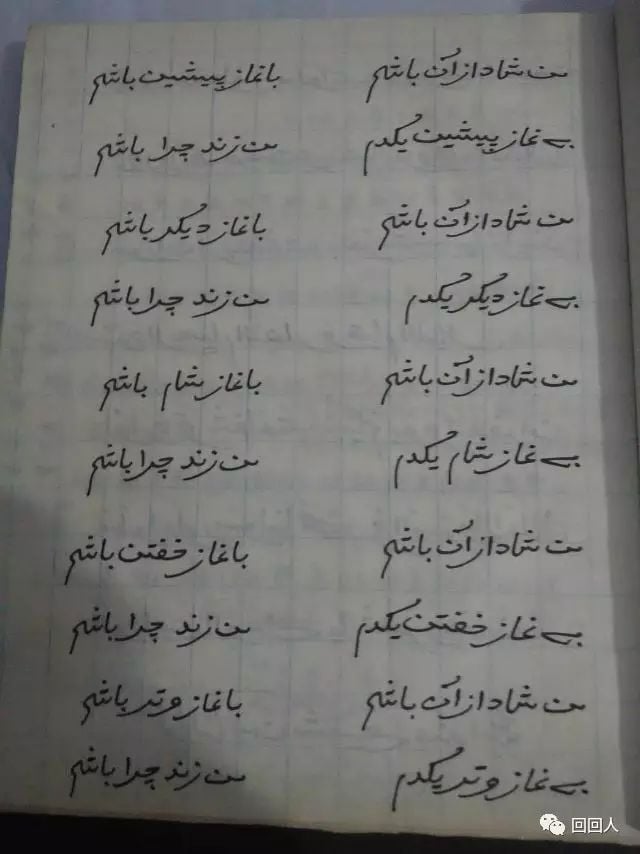

Not surprisingly, the names of all of the five Islamic prayers still in use among the Hui are from Persian rather than Arabic. These are: 榜达 bǎng dá “prayer at dawn” (from Persian bāmdād بامداد), 撇石尹/撇申/撇失尼 piē shí yǐn/piē shēn/piē shī ní “prayer at midday” (from Persian pišin پيشين), 底盖尔 dǐ gài ěr “afternoon prayer” (from Persian digar ديگر), 沙目 shā mù “prayer at sunset” (from Persian shām شام), 虎夫贪 hǔfū tān “night prayer” (from Persian khoftan خفتن). We encounter another term 阿夫他卜—府罗夫贪 Ā-fū-tā-bo fǔ-luō-fū-tān “sunset prayer” (from Persian آفتاب فرورفتن āftāb forū-raftan “sunset”) in the Persian language glossary entitled 回回館譯語 Huíhuíguǎn Literacy Primer from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Additionally, the names for the days of the week in Hui are retained from Persian: 牙其閃白 yá qí shǎnbái “Sunday”, 都閃白 dū shǎnbái “Monday”, 歇閃白 xiē shǎnbái “Tuesday”, 查爾閃白 chá ěr shǎnbái, 潘值閃白 pān zhí shǎnbái “Thursday”, 主麻 zhǔ má “Friday”, 閃白 shǎnbái “Saturday”. Of note, the Ming-era Persian-Chinese glossary Huíhuíguǎn Literacy Primer also records the Persian celebration of the winter solstice 捨卜夜勒搭 shě bo yè lēi dā (شب يلدا šab-e yaldâ), which must have been celebrated among the Hui historically.

The Hui thus bare the mantle of Persislamic civilization, with persisting use of Persian words for an array of domestic, social and religious matters in lieu of the language of the Qur’an, which would only occur among a community that used Persian as its mother language. While many Arabic terms are also used in the realm of religious vocabulary, this is expected since it is the liturgical language of all Muslims. As Michael Dillon notes:

Arabic words are used in connection with religious observance and, since the Qur’an is read and studied in Arabic, this is not surprising. More interesting is the persistence of Persian vocabulary which has social and historical as well as religious connotations. (“China’s Muslim Hui Community”, p. 154)

Hui Words Derived from Persian

A selection of Hui terms pertaining primarily to the religious sphere and their Persian roots are listed below (list composed by Afsheen Sharifzadeh):

湖達 hú-dá – “God; Allah” (from Persian خدا khodâ(y))

別安白爾 bié-ān-báiěr – “prophet [Muhammad]” (from Persian peyḡambar پيغمبر; cf. Arabic nabī نبي)

夏衣马尔旦 xià-yī-mǎ’ěr-dàn – lit. “King of mortals” (from Persian شاه مردان šâh-e mardân)

阿斯曼 ā-sī-màn – “God, sky, heaven” among Qinghai muslims (from Persian آسمان âsemân “sky”)

頓亞 dùn-yà – “world, Earth” (from Persian دنيا dunyâ)

答失蛮 dá-shī-mán – “[Islamic] scholar; learned man” (from Persian dānešmand دانشمند; cf. Arabic ‘ālim عالم)

阿訇 ā-hōng – “imam, mullah” (from Persian آخوند âkhond)

木速蠻 mù-sù-mán – “Muslim” (from Persian مسلمان mosalmān)

戴斯达尔 dài-sī-dá’ěr – “turban; cloth wrapped around head of Muslims” (from Persian dastâr دستار)

别麻日 bié-má-rì – “sick; ill” (from Persian bimâr بيمار)

依禪 yī-chán – “He, they” [referring to religious notables in place of 他们 tā-men “they”] (from Persian išân ايشان “they”)

肉孜 ròu-zī – “religious fasting during Ramadan” (from Persian roze روزه; cf. Arabic ṣawm صوم)

阿布代斯 ā-bù-dài-sī – “ablution; Islamic ritual washing of head, forearms, feet before prayer” (from Persian آبدست âbdast; cf. Arabic وضوء wuḍūʾ)

达旦 dá-dàn – “willing to marry [the woman’s term for marriage]” lit. “to give” (from Persian دادن dâdan)

卡宾 kǎ-bīn – “marriage portion; dowry” (from Persian كابين kâbin)

古瓦希 gǔ-wǎ-xī – “matchmaker, marriage broker” (from Persian گواهى guvâhi “witness”)

掃幹德 sǎo-gàn-dé – “swear, oath” (from Persian سوگند sogand)

虎士努提 hǔ-shì-nǔ-tí – “like, satisfied” (from Persian خشنود khošnud)

麻扎 má-zhā – “Muslim grave” (from Persian مزار mazâr “tomb”)

乃瑪孜 nǎi-mǎ-zī – “[Islamic] prayer” (from Persian نماز namâz, cf. Arabic صلاة ṣalāt)

古尔巴尼 gǔěr-bā-ní – “Eid al-Adha; sacrifice” (from Perso-Arabic قربان ghurbân, عيد قربان Eid-e ghurbân; cf. Arabic ضحي ḍaḥiy “sacrifice”, whence عيد الأضحى ʿEid al-aḍḥa)

班代 bān-dài – “servant, slave [of God]” (from Persian بنده bande)

朵斯提 duǒ-sī-tí – “friend or Muslim friend” (from Persian دوست dôst; note the irregular plural 多斯達尼 duō-sī-dá-ní, from Persian دوستان dôstân “friends”)

牙日 yá-rì – “friend, companion” (from Persian yâr يار)

拱北- gǒng-běi – “a small Muslim shrine” (from Persian گنبد gonbad “dome”)

邦克 bāng-kè- “adhan; Muslim call to prayer” (from Persian بانگ bâng; cf. Arabic اذان adhān)

馕 náng – “flatbread” (from Persian نان nân “bread”; cf. Arabic خبز khubz, Turkic ekmek, çörek)

郭 什 guō-shén – “meat [used by Hui to refer specifically to beef and mutton]” (from Persian گوشت gosht)

古纳罕 gǔ-nà-hǎn or 古纳哈 gǔ-nà-hā – “sin” (from Persian گناه gunâh)

哌雷 pài-léi – “fairy, genie” (from Persian پرى pari)

哈宛德 hā-wǎn-dé – “master, leader” (from Persian خاوند xâvand)

睹失蛮 dǔ-shī-mán – “adversary, enemy” (From Persian دشمن dušman)

貓膩 māonì (Beijing dialect)- underhanded activity; something fishy; trick (from Perso-Arabic معنی ma’ni “meaning; subtext or underhanded activity”), borrowed through the language of Hui

牙其閃白 yá qí shǎnbái “Sunday” (Persian يكشنبه yakšanbe), 都閃白 dū shǎnbái “Monday” (Persian دوشنبه dušanbe), 歇閃白 xiē shǎnbái “Tuesday” (Persian سهشنبه sešanbe), 查爾閃白 chá ěr shǎnbái (چاهارشنبه châhâršanbe), 潘值閃白 pān zhí shǎnbái “Thursday” (Persian: پنجشنبه panjšanbe), 主麻 zhǔ má “Friday” (Persian جمعه jum’a), 閃白 shǎnbái “Saturday” (Persian: شنبه šanbe)

榜达 bǎng dá “morning prayer” (from Persian bāmdād بامداد), 撇石尹 piē shí yǐn “prayer at midday” (from Persian pišin پيشين), 底盖尔 dǐ gài ěr “afternoon prayer” (from Persian digar ديگر), 沙目 shā mù “prayer at sunset” (from Persian shām شام), 虎夫贪 hǔfū tān “night prayer” (from Persian khoftan خفتن)

Remarkably, some conservative Hui dialects, such as the vernacular in Linxia county of Gansu known historically as 河州话 Hézhōuhuà, demonstrate Persian substratum in syntax. Of note, these dialects feature verb-final syntax, as in Persian, in contrast to standard Mandarin:

| Persian | Hui Chinese (Hezhou) | Standard Mandarin | English |

| نماز خواندى؟ Namâz khândi? | 乃瑪孜做了没有? Nǎimǎzī zuòle méiyǒu? | 做礼拜了没有?Zuò lǐbàile méiyǒu? | Have you performed [Muslim] prayer? |

References:

“CHINESE-IRANIAN RELATIONS viii. Persian Language and Literature in China” https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/chinese-iranian-viii

Dillon M. China’s Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Routledge; London, UK: New York, NY, USA: 2013.

Ford, G. (2019). The Uses of Persian in Imperial China: The Translation Practices of the Great Ming. In N. Green (Ed.), The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca (1st ed., pp. 113–130). University of California Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvr7fdrv.10

Pingback: Khwārazm: A Historical and Linguistic Analysis of the “Land of the Rising Sun” – borderlessblogger

Pingback: Persian Dominance in Commerce and Islamization on the Malay Archipelago: An Analysis of Historic Loanwords – borderlessblogger