Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. The present article delves into historic commercial and religious contacts between West Asia and the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago from the 9th to the 18th centuries AD. While one might anticipate a significant presence of Arabic loanwords in Malay related to maritime activities and commerce, the analysis surprisingly reveals that such loans predominantly originate from Persian rather than Arabic, pointing to a misattribution of influence. The author argues that a Persian-speaking merchant network played a central role in the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, shedding light on historical linguistic dynamics and questioning the presumed dominance of Arabic in certain domains.

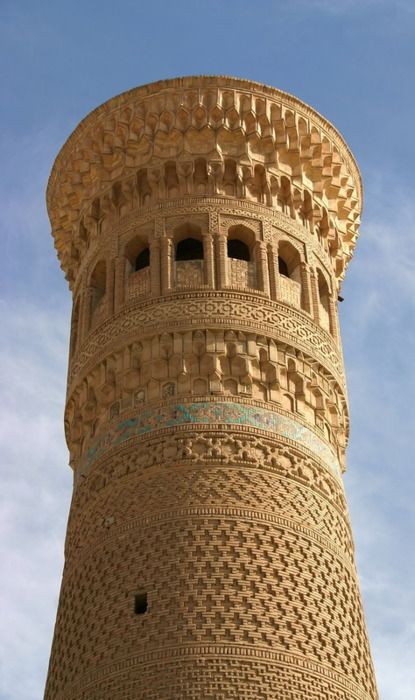

(1) Papan Tinggi cemetery complex at Barus, on the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia (2) The gravestone of one Shaykh Maḥmūd (1426 CE). The headstone is inscribed with a couplet from the Shāhnāmah (Book of Kings) of Ferdowsī (d. c. 1020 CE) addressing the subject of mortality and the impermanence of “worldly life”: جهان یادگارست و ما رفتنى/ زمرد نماند به جز مردمى “The world is a perpetual remembrance and we all leave it in the end; people will leave nothing behind but their good deeds.”

Background

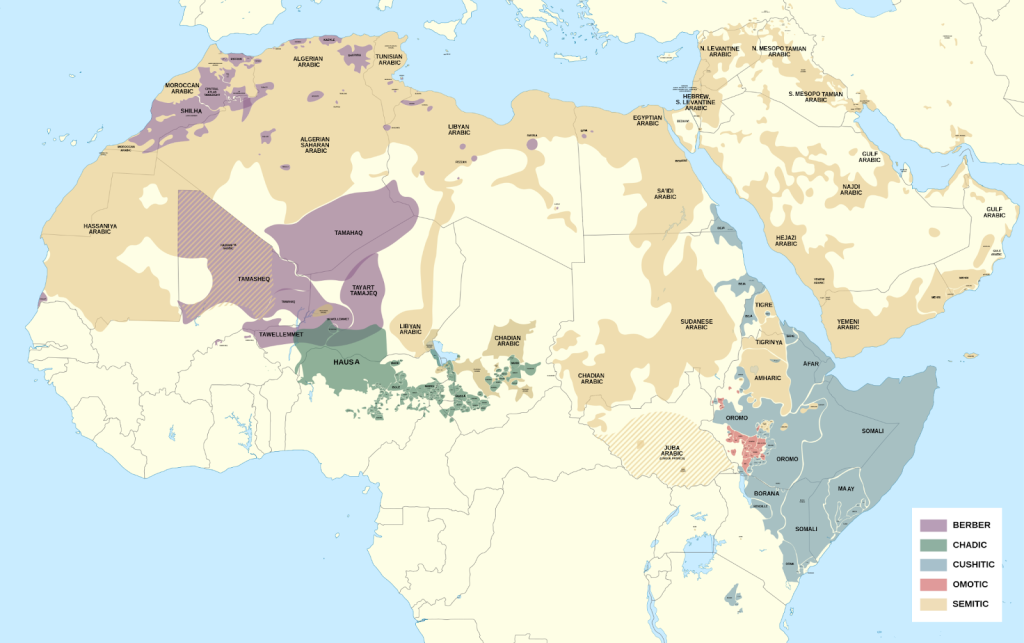

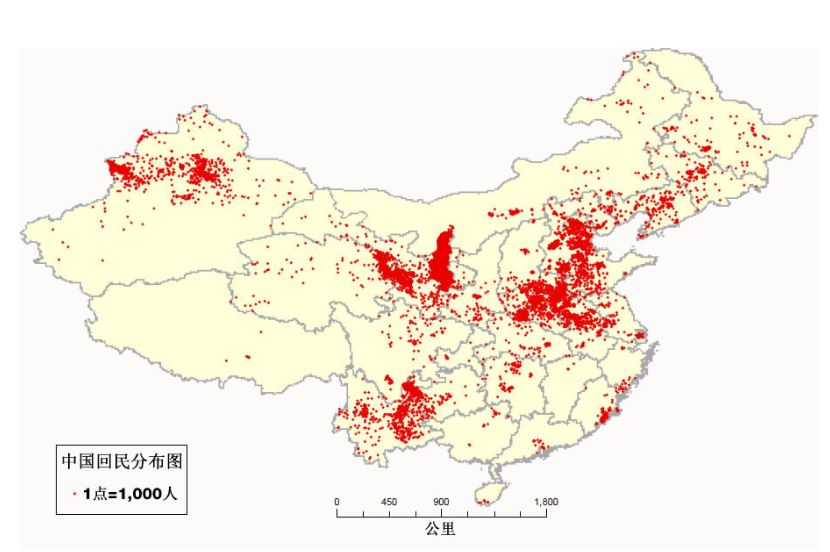

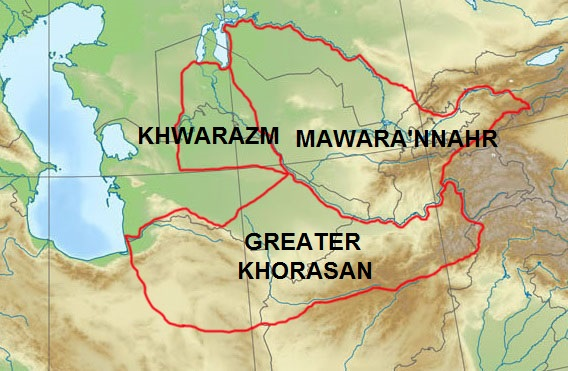

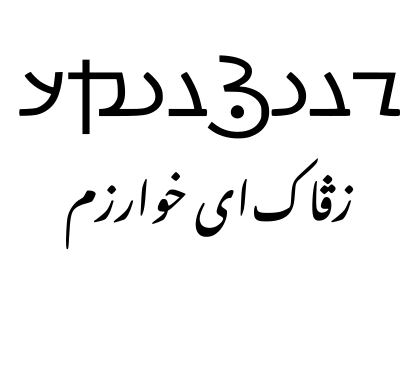

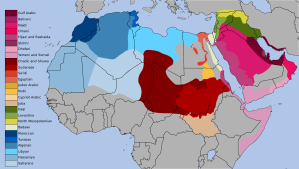

In examining commercial contacts between West Asia and the Malay-Indonesian archipelago between the 9th and 18th centuries AD, the term “Arabian” is often used to describe the foreign merchants involved in these exchanges across modern English, Malay and Indonesian language sources. We might therefore expect to encounter an array of vernacular Arabic loans in Malay (and in other indigenous Austronesian languages on Sumatra and Java, including Achehnese, Minangkabau, Javanese and Sundanese) pertaining specifically to maritime activities, commerce, and daily social exchanges. However, upon analysis, it becomes evident that loans in those domains almost exclusively originate from Persian rather than Arabic, offering a different narrative. This is in some ways unsurprising, since robust linguistic and genetic evidence have demonstrated that Persians rather than Arabs formed the dominant Muslim component in China1, the Thai Kingdom of Ayutthaya2, and the Swahili coast of Africa3, and that use of the term ‘Arab’ is in many cases the result of a broad misattribution which has been replicated for various reasons, discussed below. Observe the following Persian loanwords in Classical Malay for important nautical terms (many now obsolete or archaic), including ‘merchant’, ‘sailor’, ‘captain’, ‘harbor master’, ‘port’, ‘warrant officer’:

| Classical Malay | Persian | English |

| Anjiman | انجمن anjuman “association” | An East Indiaman; a large transport or trading vessel belonging to the East India Company |

| Awar | آوار āvār | Damage of ship or load |

| Bad | باد bād | Wind |

| Balabad | بالا باد bālā bād | High wind, land breeze |

| Bam | بام bām “ceiling” | Crosspiece (a bar or timber connecting two knightheads or two bitts on a ship) |

| Bandar | بندر bandar | Port, harbor |

| Gaz | گز gaz | A Persian unit of length, ranging from 24 to 41 inches |

| Gusi | گشا gušā | mizzen sail; gaff mainsail |

| Jangkar | لنگر langar | Anchor |

| Kelasi | خلاشى xalāši (from خلاش “rudder”) | Sailor |

| Khoja | خواجه xʷāja | Merchant |

| Nakhoda | ناخدا nākhodā | Captain, shipmaster |

| Persangga | فرسنگ farsang | A Persian measure of distance, equivalent to about four miles |

| Saudagar | سوداگر sowdāgar | Merchant |

| Serang | سرهنگ sarhang | The officer (or warrant officer) in charge of sails, rigging, anchors, cables etc. and all work on deck of a sailing ship |

| Syabandar | شاه بندر šāh bandar | Harbormaster |

| Takhta rawan | تخت روان takht ravān | Plank |

At the time of writing, the only Malay nautical terms of Arabic extraction known to this author are farsakh “an ancient Persian unit of distance, equivalent to about 4 miles” (doublet of persangga; from Persian فرسنگ farsang via Arabic فرسخ farsakh, also reborrowed into Persian as farsakh) and bahar “sea” (from Arabic بحر baḥr), but their transmission is problematic due to their simultaneous presence in Persian. If the primary participants in maritime trade were indeed predominantly Arab merchants hailing from the Ḥaḍramaut (a southern coastal region of the Arabian Peninsula), with Persians playing a secondary role in these exchanges, then the near complete absence of Arabic nautical loanwords in Malay poses a significant paradox. Why were nautical terms from the supposed ‘minority’ language selectively borrowed?

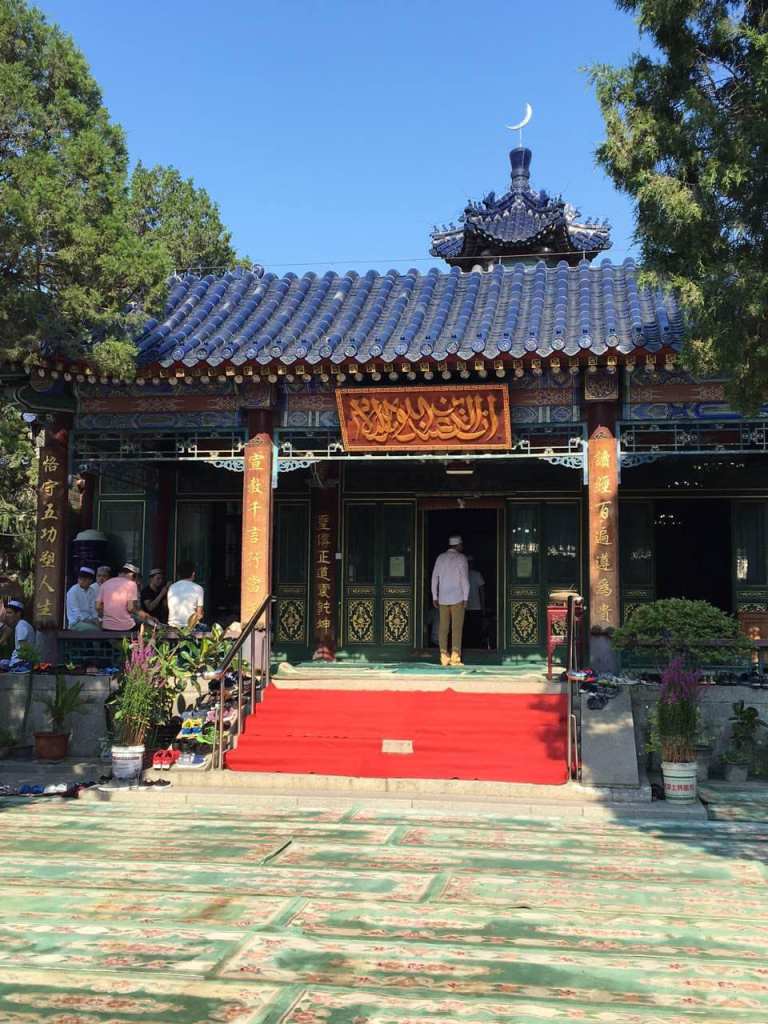

On the contrary, the remains of a shipwreck in Phanom Surin, Samut Sakhon province, Thailand dating to before the advent of Islam with an inscription of the presumed shipowner Yazd-bōzēd in Middle Persian, as well as a garnet set in gold finger ring found in Palembang, Sumatra (7th-9th century?) engraved in an elegant Pahlavi script with the Middle Persian word āfrīn, “blessing”, suggests Persians had maintained the maritime routes to China where sizable Zoroastrian, Manichaean, Christian and Jewish Iranian communities are known to have existed for centuries prior to Islam. Further Perso-Arabic, Pahlavi and Judeo-Persian inscriptions belonging to a 9th century Persian-speaking merchant community operating under state privileges on the Malabar Coast of southwest India in the same time frame as the shipwrecked Phanom Surin vessel confirms the wider network in which these objects’ discoveries must be seen. Later in the 15th century, according to the historian Ismail Marcinkowski, “…Persian was the lingua franca in the Indian Ocean trading world and a Persian-speaking merchant community was present in Malacca. The office with the Persian title of Šāhbandar (شاه بندر “harbor master”), known in many of the Indian Ocean trade ports as well as in several parts of the Ottoman Empire, was also established in Malacca.”4 This confirms and advances the existence of a longstanding Persianate commercial network in the Indian Ocean and South China Sea centered around a Persian-speaking merchant oligarchy, which in medieval times included Persian-speaking Gujaratis and Bengalis, as well as Hadhrami Arabs.

This is further corroborated by multiple foreign travelers’ attestations to the highly influential and thriving resident colonies of Persian-speaking merchants in Zaiton (泉州 Quánzhōu) in the 14th century and in Siam’s capital of Ayutthaya in the 16th century. Notably, the descendants of some of the original Persian traders in Ayutthaya (known since the 15th century by a Persian epithet Scierno, from Šahr-e nāv “City of Boats and Canals” among Western mariners and travelers around the rim of the Indian Ocean), members of the aristocratic Thai-Persian Bunnag, Siphen and Singhseni families, continued to be in positions close to the Thai throne into the 20th century. The rich and flavorful massaman curry (แกงมัสมั่น kǣng mát-sà-màn), a corruption of a Persian word mosalmān مسلمان “Muslim”, is attributed to the 17th century Persian community in Ayutthaya through Sheikh Ahmad of Qom (ca. 1543–1631), the patriarch of the Bunnag family.

(1) Tomb of the Persian-born merchant Sheikh Ahmad of Qom (ca. 1543–1631), in Ayutthaya, Thailand. He became a powerful official in the Siamese court, where he was given the title of Châophráya Boworn Râtcháyók (Thai: เจ้าพระยาบวรราชนายก). He was the ancestor of the powerful Thai-Persian Bunnag family (2) Massaman curry paste (มัสมั่น mát-sà-màn, from Persian mosalmān مسلمان “Muslim”), created by the prosperous 17th century Persian community of Ayutthaya, consists of cinnamon, nutmeg, cumin, star anise, clove, cardamom, mace (all brought by traders, including Persians, from the Malay-Indonesian archipelago to Siam) and the decidedly un-Thai flourish of raisins and bay leaves (from Iranian cuisine) combined with ingredients more commonly used in Thai cuisine such as coriander, lemongrass, galangal, white pepper, shrimp paste, shallots, and garlic. This dish, along with others inspired by Persian dishes, is among the recipes in the funeral cookbooks of the Bunnag family5

Analysis of Persian loanwords in Malay related to the goods these merchants would have brought illuminates the story further:

| Classical Malay | Persian | English |

| Almas | الماس almās | Diamond |

| Andam | اندام andām | Arrangement |

| Anggur | انگور angūr | Grapes, wine (Thai: องุ่น à-ngùn) |

| Anjir | انجير anjir | Fig |

| Badam | بادام bādām | Almond |

| Baju | بازو bāzū “arm” | Shirt |

| Baksis | بخشش baxšiš | Wage, reward |

| Balur | بلور bolūr | Crystal |

| Bius | بيهوش bi-hūš | Anesthetic |

| Bozah | بوزه būze | Fermented drink made from wheat or millet |

| Cadar | چادر čādar “tent, veil” | Bed cover or tablecloth |

| Destar | دستار dastār | Headdress |

| Gandum | گندم gandom | Wheat |

| Gul | گل gol | Rose |

| Kaftan | خفتان xaftān | A long Persian tunic |

| Kahrab | كهربا kahrobā | Amber |

| Kasa | كاسه kāse | Bowl |

| Kelebut | كالبد kālbod | Shoemaker’s last |

| Kismis | كشمش kišmiš | Raisin |

| Koja | كوزه kūza | Bottlenecked earthenware |

| Kurma | خرما xormā | Date |

| Lajak | لچک lačak | Woven fabric from yarn or silk |

| Mohor | مهر mohr | Stamp, seal |

| Perca | پارچه pārča | Cloth from remainder fabric |

| Piala | پياله piāla | Cup, chalice |

| Picis | پشيز pešiz “small” | Penny (archaic), of small worth |

| Pinggan | پنگان pengān “bowl” | Dish, plate |

| Piring | پرنگ parang “copper” | Plate |

| Pirus | فيروز firuz | Turquoise |

| Sadir | نشادر nošâdor | Ammonium chloride |

| Sakar | شكر šakar | Sugar |

| Syal | شال šāl | Shawl |

| Tembakau | تمباكو tambāku | Tobacco |

| Tenggah | تنگه tanga | A piece of gold or silver |

| Lazuardi | لاجوردى lājevardi | Lapis lazuli |

| Zamrud | زمرد zomorrod | Emerald |

On Arabic Loans in Malay-Indonesian

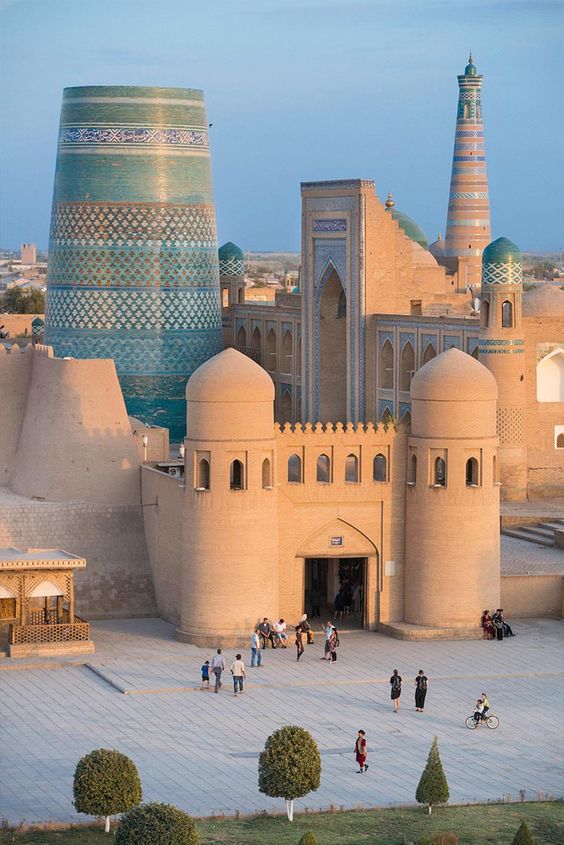

It is important to note that words with Arabic etymologies exist in high quantities in Malay (and by extension, Indonesian), far exceeding the number of ‘pure’ Persian loans. However, the majority of Arabic terms are either demonstrably (1) learned borrowings of literary provenance based on their semantic domains and unadapted phonology rather than the result of regular language contact with a vernacular Arabic variety or (2) adopted through the medium of Persian. This is not surprising since knowledge of Classical Arabic would have been prevalent across generations of Muslims even in the absence of a significant community of Arabs, since Arabic is the liturgical language of Islam and mastery of it is required for proper interpretation of the Quran and Hadith. Interestingly, the tombs of multiple Persian shaykhs in Sumatra, such as that of one Shaykh Maḥmūd from Barus dating to 1426 CE inscribed with a couplet from the Shāhnāmah (Book of Kings) of Ferdowsī (d. c. 1020 CE), indicate that Persian Muslims served as an important vector for Islamization and the transmission of Arabic to the region.

Moreover, given the presence of Persian phonologic and semantic mutations to numerous Arabic terms in Malay, many words must have been adopted through the medium of Persian rather than directly from Arabic. The number of words borrowed directly from Arabic in the opinion of this author has been, therefore, considerably overestimated. This extensive misclassification has lent false credence to the idea of a robust historic Arab–Malay relationship to the exclusion of Persians. For example, feminine nouns with the final ta marbuta ة are often, but not always, transformed to ta ت in Persian, and this is present in numerous Malay words (e.g. Malay selamat “wellbeing” from Arabic سلامة salāma via Persian سلامت salāmat; hakikat “truth” from Arabic حقيقة ḥaqiqa via Persian حقيقت haqiqat). Calques from Persian are also present which have been misattributed to Arabic influence. For example, Indonesian apa khabar? “How are you?” (lit. “what news”?) is probably a calque of Persian چه خبر če xabar? If this phrase had been calqued from a colloquial Arabic variety from the Arabian Peninsula, it would have been expected to yield something like *apa akhbar mu with the plural noun akhbar and the Malay second person possessive enclitic -mu (cf. vernacular Yemeni Arabic شو اخبارك šu axbārek). Moreover, Arabic-derived terms in Persian that are not used in Arabic must have been borrowed into Malay via Persian. For instance, the term Malay tamadun “civilization” originates from the Arabic verbal noun تَمَدُّن tamaddun “to become urbanized” but must have been adopted through Persian تمدن tamaddon “civilization” (Arabic does not use tamaddun and instead uses حضارة ḥaḍāra “civilization”, a term absent in Persian).

The arrival of the British and Dutch East India companies in the 18th century heralded the end of Persian commerce and the disappearance of Persian speakers from the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago. The introduction of steamships facilitated Malay-Indonesian contacts with sacred places and study centers on the Arabian Peninsula and in Egypt, wherefrom returning students and pilgrims began to spread puritanical ideas, particularly Wahhabism. By the 19th century the Malay-Indonesian world had directed its gaze toward Arabia rather than toward Persia, which was increasingly associated with heresy and deviant thought, particularly Sufism, pre-Islamic customs and Shi’ism. This in turn gave way to leveling of many Persian words in favor of Arabic ones, as Arabic continued to be actively studied and mastered as the holy language of Islam. Words such as aftab “sun” which were previously known in Malay, were survived only by their Arabic synonyms (Malay syamsu from Arabic شمس šams). In some cases, under prescriptive influences, Persianized Arabic words with meanings unique to Persian were supplanted by their original meanings. For example, Classical Malay logat which has the Persianized –at ending and historically held the Persian meaning of “word; dictionary” has now shifted towards the original Arabic meaning of “vernacular” but retains its Persian shape. In other cases however, such as sejarah “pedigree; history”, the Persian meaning was retained.

| Malay | Persian | Arabic | English |

| umat | ommat | umma | [Muslim] community |

| berkat | barekat | baraka | Blessing |

| tamadun | tamaddon | ḥaḍāra | Civilization |

| sejarah | šajare “family tree” | šajara “tree” | Family tree, history |

| akhlak | akhlāq “character, nature” | akhlāq “morals, ethics” | Character, nature |

| logat | loghat “word” | lugha “idiom” | 1. Word; dictionary (archaic) 2. Vernacular, idiom |

Commercial and Cultural Loanwords from Persian

Nonetheless, Persian loanwords with frequent occurrence in informal speech paint scenes of significant social interaction between Persians and the indigenous populations of the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Sumatra, and Java. This includes both positive instances of intermarriage and occasions of disagreement or conflict. Note multiple words have undergone significant reshaping, in contrast to Arabic loans, indicating their adoption through normal language contact and high frequency use. More interesting is the absence of Arabic loans in the informal register including colloquial and explicit terms (compare Malay bedebah “damned; fuck it!” from Persian بدبخت badbakht; biadab “rude” from Persian بى ادب biadab; haram jadah from حرامزاده harāmzādah “bastard”; syabas from شاباش šābāš “well done!”; etc.), which further casts doubt upon the notion that Arabic was ever used as a communication medium:

| Classical Malay | Persian | English |

| Acar | آچار āčār | Pickle, marinade |

| Adat | عادت ādat | Tradition, custom |

| Badi | بدى badi | Bad influence (obsolete) |

| Bahari | بهارى bahāri “vernal” | Beautiful (obsolete) |

| Bakh | بخش baxš | Fortunate, happy (archaic) |

| Bedebah! | بدبخت badbakht | Damned, infernal; (offensive, vulgar) fuck it! |

| Betah | بهتر behtar | Comfortable; recovered |

| Biadab | بى ادب bi-adab | Rude, impolite |

| Bustan | بستان bōstān | Garden, orchard |

| Calak | چالاک čālāk | Good, outstanding; talkative |

| Derji | درزى darzi | Tailor |

| Dayah | دايه dāya | Foster mother |

| Dewala | ديوال divāl “wall” | Wall of a city |

| Dewana | ديوانه devāna | Madly in love |

| Geman, Gamang | گمان gomān | Afraid, frightened |

| Geram | گرم garm | Indignant; angry, infuriated |

| Gusti | كشتى kušti | Wrestling |

| Haram jadah | حرامزاده harāmzādah | Bastard |

| Honar | هنر honar “craft, ability” | Mischief, commotion |

| Ini | اين in | This |

| Kanduri | خندورى khanduri | Feast, ceremonial meal |

| Kawin | كابين kābin | To get married; to have sex |

| Keskul | كشكول kaškūl | Beggar’s bowl |

| Kofte | كوفته kōfta، from كوفتن kōftan “to grind” | Various spicy meatball or meatloaf dishes |

| Nisan | نشان nešān | Tombstone |

| Panja | پنجه panje | Hand |

| Pasar | بازار bāzār | Market |

| Pesona | افسون afsun “spell, incantation” | Enthralling, dazzling |

| Pirang | فرنگ farang “European” | Blond; of a golden brown color (Thai: ฝรั่ง fá-ràng “foreigner”) |

| Sanubari | صنوبرى ṣanobari “pine-like; the slender and graceful beloved” | Heart, heartstrings |

| Serbat | شربت šarbat | A drink prepared from fruits, flower petals |

| Siuman | هوشمند hūšmand “intelligent, wise” | Conscious, mentally healthy |

| Syabas | شاباش šābāš | Bravo, well done! |

| Taman | چمن čaman “lawn, orchard” | Park |

| Tamasya | تماشا tamāšā “look, watch a spectacle” | Festival; the act of going out and looking at things |

Garnet set in a gold finger ring, engraved in Pahlavi script with the Middle Persian word āfrīn, “blessing”. Reportedly found in Palembang, Sumatra (the location of the historic entrepot of Srivijaya), 7th to 9th century. Private collection, Hong Kong

The Islamized Austronesians incorporated Persianate court styles and military culture into their societies, although most of these terms are today either archaic or rendered obsolete:

| Classical Malay | Persian | English |

| Bahadur | بهادر bahādur | Hero |

| Cambuk | چابک čābok “horsewhip” | Whip |

| Dewan | ديوان dēwān | Court, council |

| Firman | فرمان farmān | commandment |

| Geta | كت kat | Dais, throne |

| Jin | زين zin | Saddle |

| Johan | جهان jahān | World; hero |

| Khanjar | خنجر khanjar | Dagger (Thai: กั้นหยั่น gân-yàn) |

| Kiani | كيانى kiāni | Throne |

| Kulah | كلاه kulāh | A kind of helmet, headgear |

| Laskar | لشكر laškar | Army, soldier |

| Pahlawan | پهلوان pahlavān | Hero, brave warrior |

| Siasat | سياست siāsat | Tactic, politic |

| Syah Alam | شاه عالم šāh-e ‘ālam “King of the world” | Title of the sultan of Selangor |

| Tajuk | تاجک tājak | Crown |

| Takhta | تخت takht | Throne |

| Tarkas | ترکش tarkaš | Quiver |

| Zirah | زره zirih | Armor |

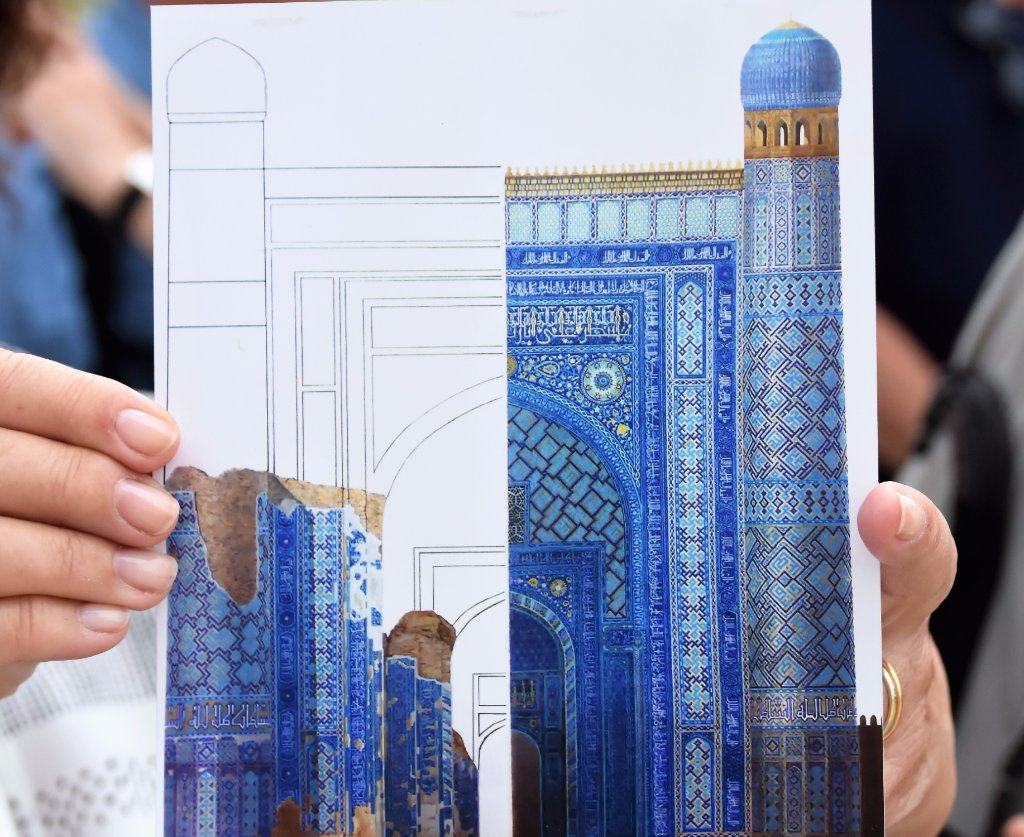

The Classical Malay literary tradition and Islamic scholarship were marked by Persian cultural influences much like on the nearby Indian subcontinent. The enigmatic Malay Sufi poet, Ḥamza Fanṣuri (of Fanṣur, modern Barus), who flourished under the reigned Sultan ʿAlāʾ al-Din Reʿāyat Šāh (r. 1588-1604), had a thorough knowledge of Arabic and Persian. In some of his works, he quotes from the masters of classical Persian mysticism such as Šabestari, either in Persian, or in Malay translation. Notable representation of the advice genre, or naṣiḥat, also bear clear parallels to classical Persian literature. An exemplary illustration of this link is the Tāj al-Salāṭin composed by Boḵāri al-Jawhari (a native of Johor in southern Malaya?) during the 17th century. This work, translated into Malay from an unidentified Persian source in the Acheh Sultanate of Sumatra, not only showcases thematic similarities with earlier Persian compositions like Neẓām al-Molk’s Siāsat-nāma but also incorporates Persian expressions, such as nowruz, to denote the commencement of a new year. Another work is Bustān al-Salāṭin also composed in Acheh around the mid-17th century by Nur-al-Din Rāniri, who was born in India and was deeply immersed in the Persian scholarly tradition. The meticulous adherence to Persian models suggests these Malay works as faithful translations. Both compositions explore the theme of the “Just King” as epitomized by Anoshervan, the archetypal ruler of Sasanian Iran.

Thus, while Arabic enjoys special status for all Muslims including Persians, much like Ecclesiastical Latin for Catholics, review of historic loanwords in Malay reveals that the majority of borrowings pertaining to nautical, commercial, military and royal domains come from Persian rather than Arabic. Persian influence is further evident in Malay literature and Sufism, which manifest concepts and styles from Persian antecedents. Arabic loans form the lion’s share in the field of religion and aspects of daily life influenced by Islamic teachings, which is expected and theoretically does not the require the presence of an Arabic-speaking community. Persian was the vector for spreading many Arabic words into Malay, which is revealed by idiosyncratic Persian phonological and semantic mutations to Arabic words. More interesting is the absence of Arabic loans in certain domains, particularly in informal speech including colloquial and explicit terms (compare Malay bedebah “damned; fuck it!” from Persian بدبخت badbakht; biadab “rude” from Persian بى ادب biadab; betah “comfortable; feeling better” from Persian بهتر behtar “better”; haram jadah from حرامزاده harāmzādah “bastard”; syabas from شاباش šābāš “well done!”; etc.), which raises doubt whether Arabic was ever used as a language of communication. Nonetheless, the persistence of few but important Persian words alongside Arabic equivalents in the religious sphere bolsters the historic importance of Persianate Islamic culture on the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago:

| Malay | Persian | English |

| Abdas | آبدست ābdast | Ablution (wudu’); compare Hui Chinese 阿布代斯 ā-bù-dài-sī, also from Persian |

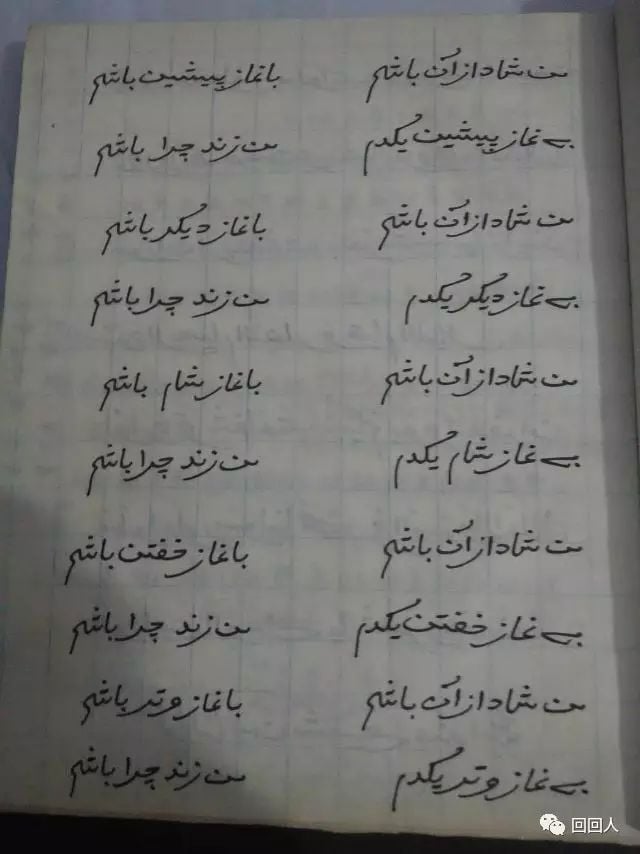

| Bang | بانگ bāng | Islamic call to prayer (adhan); compare Hui Chinese 邦克 bāng-kè, also from Persian |

| Dargah | درگاه dargāh | Shrine associated with a Muslim saint |

| Darwis | درویش darviš | An indigent, ascetic person; a Sufi |

| Langgar | لنگر langar | A small mosque |

| Peri | پرى pari | Fairy |