Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This brief survey of Muslim Baghdadi Arabic is intended for intermediate and advanced students of Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) who seek a linguistic introduction to the Baghdadi dialect by comparison to MSA and Mashriqī dialects.

Arabic dialect families. Dark green denotes Mesopotamian Arabic and yellow denotes North Mesopotamian Arabic. Note Mesopotamian Arabic dialects are also spoken in a few pockets in eastern Iran (Khorasan) and Central Asia (Uzbekistan and Tajikistan).

The colloquial Arabic varieties of Iraq belong to two main dialect groups: Mesopotamian Arabic also known as the gilit-group (Baghdad, Basra, Central Asian Arabic, Khuzestani and Khorasani Arabic in Iran), and North Mesopotamian Arabic or the qeltu–group (spoken in Mosul, eastern Syria, and by Jewish and Christian Iraqis and Anatolian Arabs). In linguistics, the gilit-qeltu paradigm is based on the different phonological systems characterizing the two dialect groups, which can be observed in the form of the word “I said”—Baghdad: gilit; Mosul: qeltu.

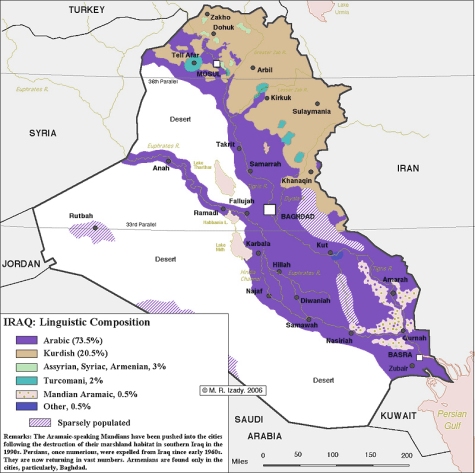

Muslim Baghdadi Arabic, belonging to the gilit-group, is the prestige dialect of the country. In this article, the term “Muslim” is used to distinguish the dialect from Jewish Baghdadi Arabic, a qeltu-group dialect that was spoken by almost one-third of Baghdad’s inhabitants until 1948, and is currently only spoken in Israel and abroad where it faces imminent extinction among the diaspora. Iraq is also home to a number of other languages, including Kurdish languages (Sorani, Kurmanji or Bahdini, Gorani, Zazaki), Neo-Aramaic and Neo-Mandaic, Turkoman (South Azeri), Armenian, and Persian.

Muslim Baghdadi Arabic is a dialect of Bedouin provenance that features several unique phonetic, lexical, and morphological paradigms vis-à-vis the surrounding Mashriqī sedentary dialects, and is layered with influences from urban Medieval Baghdadi Arabic and foreign languages such as Turkish, Persian, Kurdish, and Aramaic. This dialect, which belongs to the so-called gilit-group, should not be confused with the Iraqi dialects of the qeltu-group (Jewish Baghdadi Arabic, Christian Baghdadi Arabic, and North Mesopotamian Arabic), all of which seem to be direct descendants of Medieval Baghdadi Arabic—a sedentary medieval dialect. The qeltu-group dialects have different sound systems and morphologies from Muslim Baghdadi and also seem to have retained a greater volume of foreign loanwords that have been more vigorously uprooted from the Muslim dialect under the Ba’ath regime.

Figure 1: Mashriqī Dialect Comparison Table prepared by the author; differences between Standard, Maslāwi, Baghdādi, Damascene (Levantine) and Cairene (Egyptian) dialects. Prepared by Afsheen Sharifzadeh

| English | Standard Arabic (MSA) | Mosul, Baghdad (Jewish and Christian) | Baghdad (Muslim) | Damascus | Cairo |

| “I told you (f.)” | Ana qultu laki | Ana qeltolki | Āni gilitlich | Ana ‘eltellik | Ana ‘oltilik |

| “A lot, many, very” | Kathīr, Kathīran | Ksīɣ | Hwāye, Kullish | Ktīr | ‘Awī, Ktīr |

| “I want” | Urīdu | Aɣīd | Arīd | Biddī | ʕāyiz(a) |

| “She had” | Kān ʕandaha | Kān ʕanda | Chān ʕedha | Kān ʕenda | Kān ʕandáha |

| “I didn’t do” | Lam afʕal | Ma suwwetu | Ma sawweyt | Ma ʕamelet | Ma ʕameltesh |

| “With them” | Maʕhum | Maʕhem | Wiyyāhum | Maʕun | Wayyáhum |

| “How are you (f.)?” | Kayfa Hāluki? | Ashlōnki? | Shlōnich? | Kīfik? | Izzáyik? |

| “There exists” | Hunāk, Hunālika | Akū | Akū | Fī | Fī |

| “What” | Mādha | Ashū | Shinū | Shū | Eh |

| “Here” | Honā | Hunī | Hnāne | Hōn | Héna |

| “Now” | Al’ān | Hessa | Hessa | Hallā’ | Dilwa’tī |

| “This way, like this” | Hākadhā | Hēkī | Hīchī | Hēkē | Keda |

| “They were going” | Kānū yadhhabū | Kānū yiɣūhū | Chānow da-yerhūn | Kānu ʕam-birūhū | Kānū birūhū |

Phonemic characteristics

1.) Qāf ق is pronounced differently depending on the word. Sometimes this may seem arbitrary, but there is historical and phonemic rationalization for it. For example, in words that denote higher or abstract concepts, the Classical pronunciation of the qāf has been retained, such as the in the words حقيقةHaqīqa “truth”, مستقبل mustaqbil“future”, and اقتصاد IqtiSād “economy”. The archaic uvular pronunciation of qaaf is also retained in borrowings from Medieval Baghdadi Arabic: دقيقة daqīqa “minute, moment”, قرأ qira “he read”.

2.) In general in quotidian/mundane words of Arabic origin, there is a Bedouinization of the qāf from “q” –> “g”. For example, “I say” اقول is pronounced agūl, “I arose/began” قمت is pronounced gumit, “heart” قلب is pronounced gaLub (the “L” is emphatic), and “moon” قمر is pronounced gumar. There is also a tendency to retain the “g” phoneme in loanwords and in some instances to evolve in favor of it (i.e. khāshūga“spoon”, from Persian قاشق qāshogh). However as mentioned above, lexical borrowings from Medieval Baghdadi Arabic regardless of usage retain the Classical uvular pronunciation of qāf.

3.) In some very specific instances, the classical qāf sound is realized as “k” (q–>k). This phenomenon is observed in only a handful of words and seems to be rooted in voiced/unvoiced consonant agreement. For example, the word “time” وقت can be pronounced wakit or alternatively waqit. However, in the fixed word شوكت shwakit(“when”), only the former form is used. We also see this sound change in the 3rd person simple past of the verb “to kill” قتل, which can be heard as kital.

These pronunciations are by and large not interchangeable, and in fact switching between the “q” and “g” phonemes can result in change of meaning (i.e. farraq “to divide” and farrag“to distribute”; warga “leaf” and warqa “piece of paper”). Thus the pronunciation of qaaf depends on the word. Also as a note, the Levantine and Egyptian pronunciation of qāfق as hamza ء is not found in any Mesopotamian dialects.

The letter Dādض is always pronounced as Dhā’ظ, and Dhā’ is in turn pronounced as its classical voiced alveolar fricative pronunciation (as in Modern Standard Arabic).

Iraqi Assyrian singer Daly performs song in different languages and dialects of Iraq in this order: Muslim Baghdadi Arabic, Kurmanji (Bahdini) Kurdish, Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Muslim Baghdadi Arabic, Muslim Baghdadi Arabic, Basrawi Arabic, Basrawi Arabic.

Lexicon

Muslim Baghdadi Arabic is by no means a creole language, despite its lexical and grammatical distinctions. In fact these differences are not nearly as anomolous as features of other dialects in the Mesopotamian and North Mesopotamian groups, such as Anatolian Arabic and Khorasani Arabic. The core vocabulary of Muslim Baghdadi Arabic derives from Classical Arabic, Medieval Baghdadi Arabic, and Bedouin dialects. For a comparison of Muslim Baghdadi lexicon with other Mashriqī dialects, see Figure 1 above.

There are, however, many loanwords from peripheral languages and other areal features that have made their way into common speech via foreign hegemony, historic trade relations, bilingualism and direct contact between groups living in Baghdad. Many loanwords have become obsolete or consciously uprooted from the language, particularly within the last century.

| English | Persian | Standard Arabic | Muslim Baghdadi | Damascene Arabic |

| “Also, too” | Ham, nīz | Aydhan | Ham, hammena | Kamān |

| “By foot” | Piyāde | ʕala al-Aqdām | Pyāda | Mashī |

| “Wheel” | Charkh | Dūlāb (from Middle Persian) | Charikh | Dūlāb |

| “Manly, Womanly” | Mardāne, Zanāne | Rujūlī, Niswī | Mardāna, Zanāna | Rujūlī, Niswī |

| “Good” | Khōsh, Khūb | Jayyid | Khōsh, Zein, Helū | Mnīh, Helū |

| “Cure, remedy” | Chāre | ʕilāj | Chāra | ʕilāj |

Figure 2: Language comparison tables prepared by the author; some Persian words in Muslim Baghdadi Arabic. Prepared by Afsheen Sharifzadeh

| English | Ottoman Turkish | Standard Arabic | Muslim Baghdadi | Damascene Arabic |

| “Slow” | Yavash | BaTi’ | Yawāsh (borrowed via Persian) | Shwayye |

| “Impolite, mannerless” | Edebsiz | Gheir mu’addab | Adabsizz | ‘Alīl adab |

| “Ice cream” | Dondurma | Būdha | Dondirma | Būza |

| “My lord” (archaic) | Agham | Sayyidī | Āghātī | Sayyidī |

| “Maybe, hopefully” | Belki | Yumkin | Balkī | Yimkin |

Figure 3: Language comparison tables prepared by the author; some Turkish words in Muslim Baghdadi Arabic. Prepared by Afsheen Sharifzadeh

RT Arabic interview (part 1) with Tamara al-Daghestani, speaking in Muslim Baghdadi Arabic, while the interviewer speaks in Standard Arabic. Tamara’s family descends from warriors who were brought to Iraq from Daghestan in modern-day Russia.

Grammatical Distinctions

1.) The present progressive tense is formed by adding the prefix da- to the conjugated stem of the verb. This is likely a borrowing and adaptation from Persian into the early Abbasid-era Baghdadi vernacular. For example, “I am listening” is pronounced Ani da-asmaʕ, and “I am laughing” is Ani da-adhHak.

2.) The particle of existence as in “there is/there are” is akū and “there is not/there are not” is mākū. The origin of this word is believed to be from the southeastern Babylonian Aramaic that was spoken in central Mesopotamia prior to the Arab invasion (for further reading, see author Christa Muller-Kessler).

3.) The existence of an indeterminate indefinite article fad فد (“a, some”) that precedes the noun it describes is highly unusual and unique to Mesopotamian Arabic (i.e. “fad rijjāl, fad imreyye” = “a man, a woman”). This likely developed from the use of the Classical word fardفرد meaning “one, single (thing)” in colloquial Medieval Baghdadi Arabic (although it would have been pronounced with guttural “r” as in French and Modern Hebrew according to the sound system of that dialect, which provides insight to the development of its modern pronunciation), which is itself probably a grammatical influence from Persian or Aramaic via substrate/superstrate or bilingualism.

4.) The use of the proclitic d(i)-to add a note of impatience to an imperative verb. The role of this marker is just to intensify the sense of imperative (duklū= “eat!”, digʕud = “sit!”, digūm= “get up!”). This was originally a feature of Medieval Baghdadi Arabic.

5.) The word gām as an indicator of the future or “to begin to do something”, which is based on the Aramaic word qa’em formerly employed in Mandaic and Talmudic Aramaic.

6.) The Classical feminine 2nd and 3rd person plural pronouns are retained and exist as intan and hinna and their suffix pronouns are -chan and -hin respectively. This marked retention of feminine plurals is highly unusual among Mashriqī sedentray dialects and can be attributed to the dialect’s Bedouin origin.

7.) Sometimes colloquially there is an omission of the future tense altogether (an influence from Persian). For example “I will come with you” can be expressed Āni ajī wiyyāk.

8.) Muslim Baghdadi Arabic has consonant harmony, which is essentially the ability of certain consonants (emphatic consonant, bilabials, and velars) to affect or “color” the quality of the vowel they occur directly next to. For example, gumar <— Classical قمر qamar (“moon”) ; buSal <— Classical بصل baSal (“onion”); sima <— Classical سماء samā‘ (“sky”).

It is important to note that all lexical and syntactical features of Aramaic origin have reached Muslim Baghdadi Arabic through the medium of Medieval Baghdadi Arabic, rather than direct contact, because that would be inconsistent with the historical development of Muslim Baghdadi Arabic both chronologically and socio-culturally and would not align correctly with the “life span” of those Aramaic dialects.

Another point of interest is the affrication of Kāf ك to “ch” (k–>ch), which is a Bedouin feature. This occurs again mostly in quotidian words or lexical borrowings from Persian and Turkish. For example, the past tense of the verb “to be” كان kāna is conjugated as follows:

| English | Modern Standard Arabic | Muslim Baghdadi |

| “I was” | Ana kuntu | Āni chinit |

| “You (m.) were” | Anta kunta | Inta chinit |

| “You (f.) were” | Anti kunti | Inti chinti |

| “He was” | Huwa kān | Huwwa chān |

| “She was” | Hiya kānat | Hiyya chānat |

| “We were” | Nahnū kunna | Ehna chinna |

| “You (pl.) were” | Antum kuntum | Intū chintū |

| “They were” | Hum kānū | Humma chānōw |

Figure 4: past tense of كان kāna in Muslim Baghdadi

In quotidian words of Arabic origin, the “ch” pronunciation is favored over “k”, although there is incidence of both:

kalbكلب —-> chalib (“dog”)

shubbākشباك —-> shubbāch (“window”)

kabīrكبير —-> chibīr(“big, large”)

bakā‘بكاء —-> bachī(“cry, weep”)

sikkīnسكّين —-> sichchīna(“knife”)

kidhdhābكذاب —-> chedhdhāb (“lier”)

In lexical borrowings:

chakūch = “hammer” (from Persian via Turkish)

-chī= archaic occupational suffix, as in qundarchī“shoemaker” (from Persian via Turkish)

charpāya= “bed, stand” (from Persian)

chakmak = “boots” (from Persian)

chāi = “tea” (from Persian)

pācha = a traditional dish consisting of sheep’s head and hooves (from Persian)

In some instances, foreign lexical borrowings have adopted the “ch” sound when they originally lacked it: chafchīr = “spatula, large pouring spoon” (from Persian kafgīr)

The k–>ch sound change also serves an important morphological purpose–namely, to distinguish between masculine and feminine personal suffixes. The masculine form is -k while the feminine form is -ch. Ex:

Akhūk= Your (m.) brother

Akhūch= Your (f.) brother

Wiyyāk = with you (m.)

Wiyyāch = with you (f.)

“Good Morning Arabs” interview with Iraqi poet, Shahad Shammari, speaking Muslim Baghdadi Arabic while the interviewer speaks Emirati.

The non-Arabic phoneme “p” also exists in Muslim Baghdadi Arabic, but only in loanwords, and can often be used interchangeably with “b“.

parda = “curtains” (from Persian)

pālTo= “overcoat” (from French via Persian)

pāsha= “high ranking official” (from Persian via Turkish)

Salmān Pāk= a town north of Baghdad near the Sassanid-era ruins of Ctesiphon (المدائن), named after a Persian companion of the prophet Muhammad

pūlādh= “steel” (from Mongolian via Persian)

However, some words have been irreversibly adapted to the standard Arabic sound system and have undergone the resulting sound change “p” –> “b”. Curiously enough, the resulting “b” sound is often emphatic:

toBa=”ball, cannonball” (from Turkish top)

guBBa = “room, vault” (from Persian qoppeh)

Thank you for this informative article about the Iraqi dialects.

I really enjoyed and benefit from this article and id like to have the fall work of it if is available, thank you so much.

Is there a dictionary you can recommend for the Muslim Baghdadi dialect?