Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. The goal of this article is to familiarize the reader with the looks and feels of Chechnya, its people and language in a historical and modern setting.

Traditional Chechen dance among youth. Many Chechens in the Russian Federation live outside of the Chechen Republic in other subdivisions of Russia, particularly Daghestan, Ingushetia, Rostov, Moscow and Tyumen in Siberia. Note that the Chechen dance repertoire is typologically Caucasian in style, bearing close resemblances to folk dances found in Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and other Russian federal subjects in the North Caucasus. The Chechen repertoire is distinguished by a double-step stride; each dancer taps first with the point of the foot followed in rapid succession by a heel stomp to compose a single stride, in effect creating a gallop-like aesthetic.

The Chechen Republic in Russia

Forced population movement is a bitter and tantalizingly familiar memory in the Caucasus. For centuries, neighboring superpowers have used the Caucasus as a playground for showcasing grand military gestures and executing socio-strategic gambits vis-à-vis each other, all the while imperiling the condition of the region’s native inhabitants. It is nonetheless a grave misfortune—both socio-economically and psychologically—for any human being to be uprooted from his or her home and forcibly resettled in a far away land, and indeed the act can have dire consequences for the continuity of a people and culture. In the Soviet Union in 1944, the entire Chechen (and Ingush) nationality was deported en masse from their home of 6,000 years in the North Caucasus and dispersed throughout sparsely-populated Siberia and Central Asia. Death estimates range between 20%-50% during removal, which took the form of a month-long exodus packed in cattle cars ridden with disease and starvation. Survivors began returning sporadically after Stalin’s death, especially after 1957 when return was officially permitted although discouraged. This is the setting in which the Chechen-Ingush ASSR was born, and later the Chechen Republic at the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Since then, Chechnya gained de facto independence from Russia after the First Chechen War in 1996, only to have Russian Federal control restored after the Second Chechen War three years later in 1999. This article builds a bridge to the Chechen people and their history, bypassing politics and modern history, and instead relying on culture, language and tradition to serve as the golden diplomats between the reader and the Chechens.

Defense towers in the village of Erzii in Dzhayrakh, Ingushetia. According to local ethnogenesis myths, the town of Erzii, which is an Urartian loanword meaning “eagle” (also survives in Armenian: արծիվ “artsiv”), is the spawn of the Chechen and Ingush people, who are together self-designated “Vainakh”.

The Chechens and their Language

It is said that when God created the world, he sprinkled nations over the globe, but clumsily dropped his shaker over what ancient travelers called the “mountain of languages”. Pliny wrote that the ancient Greeks needed 300 interpreters to conduct business in the North Caucasus, while later, “we Romans conducted our affairs there with the aid of 130 interpreters.”

In general, when mountains are inhabited by settled farming and herding people, they harbor unusual diversity of language families and grammatical structures relative to nearby lowlands. It thus follows that the Caucasus is as distinct linguistically as it is geographically and biologically. In fact it is the one of the most ethno-linguistically diverse regions by area on the planet. Packed in the tight valleys and coniferous thickets of the Caucasus mountain system connecting “Europe” to “Asia”, flanked on either side by the Caspian and Black seas, live humans who speak languages and dialects belonging to no less than six (or seven, depending on the informant) unrelated linguistic macrofamilies. In comparison, mainland Europe is inhabited natively by speakers of a total of three. Indo-European, Semitic and Altaic are minorities here, while Northeast Caucasian (Daghestanian), Northwest Caucasian (Abkhazo-Adyghean), North-Central Caucasian (Nakh), and South Caucasian (Kartvelian) are the dominant families and only exist here on Earth. The genetic affinities between these four groups are uncertain and improbable, although some—including this author—posit a remote relationship between Daghestanian and Nakh and postulate a split at the Proto-language stage some 5,000-6,000 years ago. The only Caucasian language with an old literary tradition is Georgian (belonging to the South Caucasian or Kartvelian family) with its own alphabet dating back to the 5th century A.D., while the others have acquired Cyrillic-based alphabets and literature within the past century or so (Note: Armenian, an Indo-European language native to the Caucasus with its own alphabet, also has a literary tradition dating back to the 5th century A.D. alongside Georgian, coinciding with the spread of Christianity to those peoples).

Map of ethno-linguistic groups in the Caucasus region. The Caucasus (Transcaucasia and Ciscaucasia) is one of the most ethno-linguistically diverse regions in the world.

Chechen belongs to the North-Central Caucasian (Nakh) language family, along with Ingush and Bats (spoken in one small village in the Kakheti plain in Georgia). The Batsbi people, whose language is about as related to Chechen and Ingush as English is related to Dutch and German, do not follow Vainakh customs and law and consider themselves Georgians. The Chechen-speaking Kisti people of northeastern Georgia have also been Georgianized in their surnames and national consciousness and do not identify with the Batsbi or Vainakh.

A Georgian group singing an Ingush (Nakh family; close relative of Chechen) folk song in Georgian (Kartvelian family) about a Kisti maiden. The Kisti descend from Chechen tribes that migrated into eastern Georgia (Pankisi) from the highlands in the middle of the 19th century, and have retained their language. The tune is typical Caucasian ballad repertoire.

Chechen (Nokhchii muott) and Ingush (Ghalghaa muott), the two main members of the Nakh language family, are mutually unintelligible although inextricably akin to each other. They have 83-84 percent retention of strict cognates on the Swadesh 100-word list, so their date of separation is roughly twelve hundred years ago, around 800 A.D. As such, there is much passive bilingualism between their speakers, so the two languages function as a single speech community (See Table 1). Chechen and Ingush also feature many loanwords and areal features (phonetic and morphological) from surrounding languages– particularly Daghestanian languages, Russian, Arabic, Turkic languages, Georgian, Armenian and Iranian languages.

| English | Chechen | Ingush |

| “Friend” | Dottagh | Dottagh |

| “Mountain” | Lom | Loam |

| “Man” | Stag | Q’uonakh |

| “Black” | ‘ärzh | Wearzh |

| “Scary, terrifying” | Inzari | Unzari |

| “Ant” | Dzintg | Dzungt |

Table 1: Language comparison table prepared by the author illustrating relationship between Chechen and Ingush

A Late 19th century Batsbur wedding in the village of Zemo Alvani in eastern Georgia. The Batsbi speak a Nakh language about as akin to Chechen and Ingush as English is to German or Dutch.

To speakers of most modern Eurasian languages, Chechen appears to contain a number of unusual features. Phonologically, the language contains a wealth of sounds similar to Arabic and Swedish–namely 44 vowels and between 40 and 60 consonants depending on the dialect– far more than any European language. Chechen nouns belong to one of six “genders” or “classes” and can be declined using eight cases. The verb “to be” follows a particularly unique pattern: all nouns are assigned a set form: du, vu, yu, bu, (“is”) which must be memorized along with the noun and in turn colors all corresponding adjectives and verbal constructions.

Chechen: Ha byargsh haz bu

English: “Your eyes are beautiful”

Chechen: Ho sun 1elch yoghur yu

English: “You (f.) are coming to me”

Chechen: Sa dog q1andel hozun dog san dats’

English: “My heart is not like that of an old bird”

A traditional wedding in Chechnya, according to a mixture of Chechen and Muslim customs. Brides throughout Central Asia and the Caucasus follow a custom of refraining from smiling or showing joy on the wedding day, so as to keep away others’ envy of their fortunateness.

Origins and Ethnic Identity

The Chechen people call themselves Nokhchii; the ethnonyms “Chechen” and “Ingush” are Russian designations. Together the Chechen and the Ingush (self-designated Ghalghaa) compose Vainakh (literally “our people”), recognizing an overarching ethnic and linguistic kinship despite their longstanding distinct national consciousnesses and self-designations. Clan origins or ethnogenesis myths among the Vainakh all feature immigrant progenitors who traveled northward, married into a preexisting Caucasian ethnic group, and founded a new highland village among prior inhabitants. Most clans claim roots in Arabia, Syria, and Persia, and the Chechen nationality as a whole claims descendance from one such Syrian immigrant.

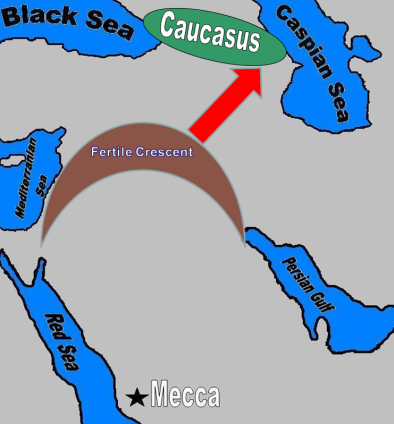

From a strictly evidential standpoint, the question of when and wherefrom the Nakh people (Chechens, Ingush, Batsbi and Kisti) arrived in the Northeast Caucasus remains shrouded in what seems to be impenetrable uncertainty for linguists and anthropologists. Aside from a few moderately-convincing attempts to pin a remote link with Daghestanian languages at the Proto-language stage, Nakh appears to be unrelated to any other attested primary language family on the Eurasian landmass, even at the magnitude of ~15,000 years. It is nonetheless widely held by some authors such as Amjad Jaimoukha, Johanna Nichols and Bernice Wuethrich that the Nakh peoples represent a periphery group that migrated (or perhaps, returned) out of the Hurro-Urartian-dominated Fertile Crescent and into the Caucasus some time after 10,000 B.C., perhaps displaced there by push factors such as the overuse of land and subsequent creation of vast deserts in Mesopotamia. This in turn places the ancestors of the Nakh peoples before the Sumerians and archaic Semitic-speaking peoples of Akkad and Babylon as the proprietors of Mesopotamia by several thousand years, and corroborates Igor Diakonoff’s suggestion of remote ties between Hurro-Urartian languages and Northeast Caucasian.

Mounting linguistic evidence suggests that the Proto-Nakh peoples who would later differentiate into the modern Chechens, Ingush, Batsbi and Kisti may have migrated to the slopes of the Caucasus from the Fertile Crescent some time between 10,000 B.C.-8,000 B.C., although the issue of their origins still remains shrouded in mystery.

Following a supposed trajectory of Nakh transhumance into the Caucasus mountain system after 10,000 B.C., the empirical evidence we have indicates that the historical region inhabited by Nakh tribes was much larger and included areas now dominated by Ossetians (Iranian branch, Indo-European family) and Georgians (Kartvelian family). An isogloss map reveals that the original Nakh-Daghestanian center of gravity probably lies in modern day Georgia, south of the Great Caucasus range, but these peoples were gradually displaced to the highlands by Kartvelian transhumance prior to the late Middle Ages. Historically then, modern Chechen-Ingush descend from nonfrontier languages that show no evidence of contact with exotic languages throughout their prehistory, indicating that they were once surrounded by now-extinct sister languages also belonging to the Nakh-Daghestanian language family (of which Bats in Georgia is the only survivor). Indeed, Nakh language-speaking clans were historically far larger in spread and influence south of the Caucasian piedmont.

Tusheti and Khevsureti, the proposed homeland of Nakh-Daghestanian peoples (including Chechens and Ingush), lies south of the Great Caucasus range in modern-day Georgia.

Religion and Social Organization

The Chechens are divided into clans, or taips (from Arabic طائفة Tā’ifa) which then belong collectively to a grand alliance of familial clans called tukhkhums (from Armenian տոհմ tōhm, itself a Middle Persian borrowing). At the moment, the Chechens are united in 9 tukhkhums, comprising more than 100 taips.

Chechens are predominantly Sunni Muslim following their recent conversion to Islam between the 16th and 19th centuries, and belong primarily to the Shafi’i school of jurisprudence (fiqh). Of note, Sufism is popular among Chechens, and many Chechens belong to the Qadiri and Naqshbandi orders. Most of the conversion took place in the 19th century during the Russian imperial invasion of the then Persian-controlled Caucasus, with the intent of bringing groups together in anti-colonial resistance movements, in turn giving them state-like forms of organization. In the 19th century, the tribes to the west and east Caucasus became Muslim (Chechens, Ingush, Circassians, Avars, Lezgins, Dargins, etc.), while the millennium-old Eastern Orthodox Christian communities in the central section (Ossetians, Georgians, Abkhazians, Armenians) remained Christian in their majority through the present. The Jewish Lak people of Daghestan and the Judeo-Tats of Azerbaijan retained their religion from prior to the mass conversions.

Prior to their conversion to Islam just two centuries ago, the majority of Chechens and Ingush followed their own polytheistic tree-worshipping religion or were affiliated with Eastern Orthodox churches. At the center of the indigenous Vainakh religion was the pear tree, and adherents belonged to a mixture of different cults, including animism and polytheism, familial-ancestral and agrarian and funeral cults. Interestingly, in modern Chechen the name of the supreme pagan god, Dela, is still in use alongside Allah as a word to denote the Abrahamic God, not dissimilar to the Turkic and Mongol usage of tenri/tengri.

The Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque in Grozny, capital of the Chechen Republic, Russia. Modeled off of the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, it is the biggest mosque in Russia.

The Nart Saga

The Nart saga is a series of tales about a mythical race of giants shared among the peoples of the North Caucasus. The term Nart is most likely Iranian (Ossetian) in origin, although some posit a Mongolian etymology. Nonetheless, it is generally known that all the Nart corpora have an Iranian core, inherited from the Scythians, Sarmatians and Alans (ancestor of modern Ossetians)– all of whom were Iranian peoples that once dominated the Eurasian Steppe in modern day Russia, Central Asia and and Eastern Europe. These tales played a vital role in the indigenous religions and cults of the peoples of the North Caucasus, including Circassians, Abkhazians, Ossetians, Chechens, Ingush, Daghestanians, and others, and continue to occupy an important position in the folk traditions of those peoples.

A Kabardian (Circassian; Northwest Caucasian) dance group performing a tale from the Nart Saga. The Nart saga is shared among the folklore of the Adygheans, Cherkess, Kabardians, Abkhaz, Abaza, Chechens, Ingush, and Ossetians in the North Caucasus.

Chechen Diaspora in the Middle East

Within subdivisions of Russia outside of the Chechen Republic, Chechens mainly descend from refugees who were forced to leave Chechnya the 19th century Caucasian War, the annexation of Chechnya by the Russian Empire, and the 1944 Stalinist deportation to Soviet Siberia and Central Asia (discussed above). These peoples are centered in neighboring Daghestan, Moscow Oblast, Ossetia, Kazakhstan, Georgia (excluding the Kisti and Batsbi people), Sweden and the United States.

However, there is a fascinating narrative surrounding Chechen diasporas now located in the Middle East. In the middle of the 19th century, approximately 1 million 400 thousand North Caucasians Muslims–Chechens, Circassians and Daghestanis–were forced to migrate out of the Orthodox Christian Russian territories and settle with their coreligionists in the Ottoman Empire. Only the Chechens of Jordan, particularly a community of 450 souls in al-Suknah, have retained their language, as well as clothing and marriage customs. This is in great part due to royal favoritism on the part of the Hashemite family of Jordan. Chechens in Turkey, Syria, Egypt and Iraq have been assimilated linguistically, but continue to practice a few customs and identify as Chechens. In the 16th-17th centuries, Caucasians (particularly Georgians, Armenians and Circassians) were also forcibly uprooted, oftentimes converted, and resettled throughout Persia and the Ottoman Empire. But any Nakh deportees from that period have completely assimilated, and no traces remain of their language or culture.

Documentary on the tight-knit Chechen community of Jordan (in Russian and Chechen)

Sources

Jaimoukha, Amjad. “The Chechens: A Handbook.” Caucasus World: Peoples of the Caucasus. Taylor & Francis, 2004.

Kailani, Wasfi. “Chechens in the Middle East: Between Original and Host Cultures.” Caspian Studies Program.

Nicols, Johanna. The Origins of the Chechen and Ingush: a Study in Alpine Linguistic and Ethnic Geography. Anthropological Linguistics. Vol. 46, No. 2 (Summer, 2004), pp. 129-33

Vol. 288 no. 5469 p. 1158

Thank you so mich for this article. There is not much knowledge about the chechen history because russians destroide it under the war. The little we get to know is gold worth.