Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This article provides a brief history of the Zoroastrian (Mazdean) religion and the Ādur Gušnasp fire temple located at Taḵt-e Solaymān (Shīz), Iran, which served an important role in the religious and political framework of the Sasanian Persian Empire

(1-5) The ruins of Ādur Gušnasp Fire Temple are situated on an extinct volcano 2,150 meters above sea level at Shīz, Iran. The complex sits atop sediments formed from the overflowing calcinating water of a thermal spring-lake (21° C) which formed in the volcano’s extinct crater. The site transports the observer to a bygone era, in which lofty passageways illuminated by the eternal fire’s soft glow would grant access to a large domed chamber housing Ādur Gušnasp in a grand stone fire-altar

Background

Immediately before the advent of Islam, a diverse range of religious beliefs existed among Iranian peoples, who once inhabited a vast region spanning from Gelonus to Seleucia-Ctesiphon to Khotan. These included native Iranian faiths such as Zoroastrianism (incl. Zurvanism), Manichaeism, Mazdakism, varieties of Iranian polytheism and the Scythian religion, as well as Indic traditions like Buddhism (Tantric Vajrayāna) and Abrahamic religions such as Christianity (Church of the East), Judaism and Gnosticism. However, Zoroastrianism (also called Behdin “the Good Religion”, Mazdaism or Mazdayasna, lit. “wisdom-celebration”) held the sole position of official patronage within the Sasanian Persian Empire beginning with Ardeshir I (r. 226–241 A.D.), the founder of the dynasty and grandson of the eponymous Zoroastrian high-priest of Staḵr, in Pārs, named Lord Sāsān (Sāsān xʷadāy). By the reign of Shapur II (r. 309–379 A.D.), it was declared the official state religion in a move, in all probability, to curtail sympathies towards the Christian state church of its archenemy, the Roman Empire. The Zoroastrian attitude of non-proselytization, however, fostered a policy of religious tolerance—a tradition started by the Persian Achaemenids and continued by the Arsacids—which facilitated strategic inclusivity of Christians, Gnostics, Jews, Manichaeans and Buddhists as a means of sustaining social harmony. Central to Zoroastrian ethics is the concept of personal agency and individual choice as a result of free thought; thus, proselytization was discouraged, while self-initiated conversion was welcomed. By contrast in the Roman Empire, coercive conversion and persecution against non-Christians was frequently used as a tool for maintaining societal cohesion.

(1) A large relief of the investiture of the Sasanian king Ardashir II at Tāq-i-Bustān, Kermānshāh, Iran (c. 4th century A.D.). King Ardashir II and his predecessor Shapur II stand atop the fallen Roman Emperor Julianus Apostata (361-363 A.D.). The archangel (yazāta) Mithra stands atop a Lotus Flower on the left holding a “barsom”—a bundle of twigs from select medicinal plants used by Zoroastrian priests (Magi) in their role as traditional healers. (2) Gold statuettes carrying barsoms, a symbol of priesthood, discovered as part of the Achaemnid-era “Oxus Treasure” in Qobādiyān, Tajikistan.

As a result of gaining official status, concerted efforts were made in early Sasanian times (224-651 A.D.) to collate, edit and systematize the liturgy with the purpose of compiling a master copy of the scripture known by its Middle Persian name Abestāg (NP: Avestā; perhaps from Old Iranian *upa-stāvaka- “praise”). This so-called ‘Sasanian archetype’ canonized an assortment of written and oral traditions, many of which had been composed by priests in times far removed from the lifetime of Zoroaster (c. 1500-1000 B.C.?), in a manner deemed suitable for the likes of an organized state religion. A complete version of the holy scripture likely existed in the Achaemenid epoch (550–330 B.C.), “written on adorned ox hides with golden ink” and housed at the Fortress of Archives (diž ī nipišt) at Staḵr in Pārs. Lamentably, it and other copies were targeted and destroyed by Alexander of Macedon (ōy petyārag ī wad-baxt ī ahlomōγ ī druwand ī anāg-kardār aleksandar ī hrōmāyīg “that wretched, ill-omened adversary, the accursed, evil-doing heretic Alexander the Roman”), who also executed scores of the foremost “religious authorities (dastwarān), judges, hērbeds, mōbeds, religious leaders, and able and wise people of the land of Iran” according to the Sasanian-era Ardā Wirāz Nāmag.

The Sasanian descriptions further state that this original Avesta consisted of twenty-one Nasks or books, and must have been a sort of encyclopædia, not alone of religion, but of many matters relating to the arts, sciences, and professions, closely connected with daily life. It is speculated that among the lost materials were the descriptions of perhaps hundreds of botanical medicines, including the revered haoma (𐬵𐬀𐬊𐬨𐬀 “ephedra”[?], Zoroastrian Dari: هم hōm; a powerful stimulant). This is reflected in the Magi’s ancient renown as physicians and healers who are frequently depicted holding twig bundles (𐬠𐬀𐬭𐬆𐬯𐬨𐬀𐬥 barəsman; MP: barsom), a symbol of priesthood, which they used to prepare a wide array of plant-based extracts.

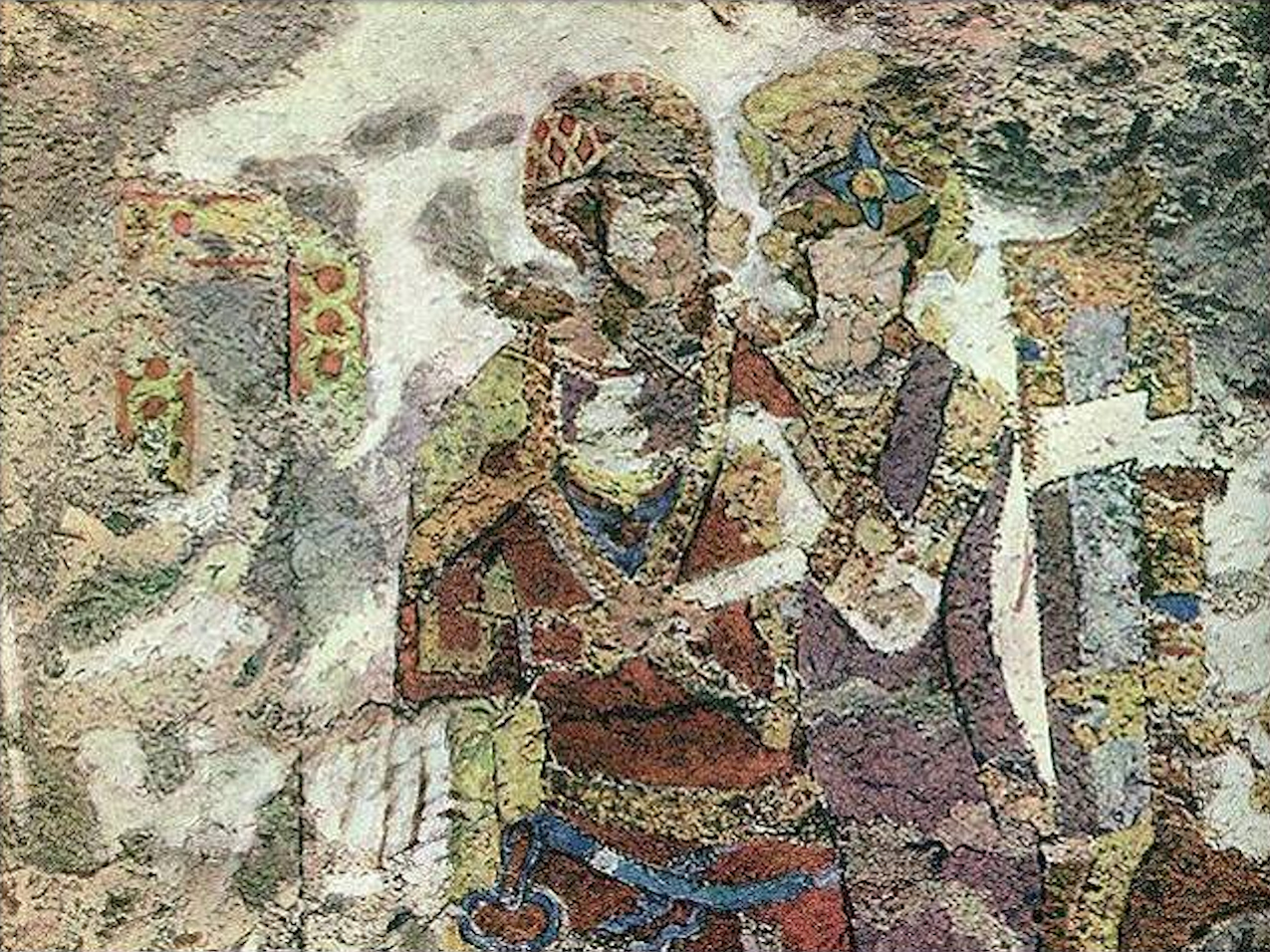

(1-2) Remnants of murals found in the fire sanctuary gallery at Kūh-e Xʷāja, Sistān, Iran. It appears in the Sasanian period, sacred Zoroastrians precincts had a wealth of luxurious decorations. Aurel Stein observed a three-headed creature and an ox-headed mace (gorz) held by a partially-obliterated seated figure in the first painting, identified as the hero Rostam with his weapon (3) The imposing south façade of the fire sanctuary bears the remnants of a stucco relief that portrayed a contest between a horseman and a lion (4-5) The Kūh-e Xʷāja complex sits on a basalt lava island in the historic Lake Hāmūn. Offerings to water, seen as nurturing the cosmic integrity and strength of the natural element, serves as the culmination of the daily Zoroastrian act of worship

Judging from the table of contents of the Nasks, it would seem that not more than a quarter, perhaps less, of the ancient monument of the Avesta could be restored even at the time of the Sasanian council. Nonetheless, reformists contend that this move on the part of the Sasanian monarchy introduced a host of stringent laws and disagreeable practices—particularly in the form of the Vīdēvdād (lit. “Given against Demons”) ecclesiastical code—that reflect contemporary attitudes among the clerics and communities who conceived of them rather than the abstract, progressive and morally profound tenets set forth by Zoroaster in the Gāthās over a thousand years prior. Indeed, the spirit of the Gāthās is largely non-prescriptive in that it promotes self-dependent righteousness as a result of freethinking and free will, as well as ecological stewardship in nurturing the cosmic integrity of water, earth, the animal and plant kingdoms, air and fire. The immortal personal spirit (Av. 𐬟𐬭𐬀𐬎𐬎𐬀𐬴𐬌 fravaṣ̌i; OP *fravarti- –> MP frawahr –> NP فروهر farvahar, forūhar) of each individual, residing somewhere in the intangible universe (Av. 𐬨𐬀𐬌𐬥𐬌𐬌𐬎 mainiiu “spirit [realm]”; MP 𐫖𐫏𐫗𐫇𐫃 mēnōg –> NP مينو mīnū), sends out the urvan (𐬎𐬭𐬬𐬀𐬥 ‘soul’; NP روان ravān) to take transient bodily form (𐬙𐬀𐬥𐬎 tanu; NP تن tan) in the material world (Earth; MP 𐫃𐫏𐫤𐫏𐫃 gētīg –> NP گيتى gītī)) which serves as the final battlefield in the eternal struggle between the forces of light, truth and intelligence and those of darkness, falsehood, and ignorance. On Earth, the individual possesses free will to act as a co-worker—rather than a slave—of Ahura Mazda and the forces of light or of his demonic adversary, Angra Mainyu (𐬀𐬢𐬭𐬀⸱𐬨𐬀𐬌𐬥𐬌𐬌𐬎; NP: اهريمن Ahrīman), without dooming repercussions, given the predicted final victory of good over evil and the universal salvation of souls. The Gāthās speak naught to matters such as disposal of corpses, bodily defilement and ritual purification, sodomy, and gender roles as outlined in the Vīdēvdād, whose authors were Magi writing in an unknown geographic location at a time far removed from that of their prophet, when Avestan had already ceased to be spoken, in a deliberately imitative but degenerate form of the Gathic language (Artificial Younger Avestan).

(1) A Zoroastrian priestess directs worship towards God (𐬀𐬵𐬎𐬭𐬋 𐬨𐬀𐬰𐬛𐬃 Ahurō Mazdā̊, lit. “Lord of Wisdom/Intelligence”) before the soft glow of an eternal fire during the ‘Sadeh’ festival, Tehran, Iran (c. 2020) (2) A priestess carries a vase of coals in order to set firewood ablaze for the expansion of an eternal fire for ‘Sadeh’ (3) Sadeh (lit. “one hundred”) is celebrated one hundred days and nights past the end of the summer. A massive bonfire is ignited using embers from a sacred temple fire to symbolize the ultimate triumph of light and positivity over darkness, cold and frost.

Since the establishment of the temple cult of fire likely in the late Achaemenid period (detailed below), Zoroastrians have frequently been known among followers of other faiths as “fire-worshippers”. However, Zoroastrians themselves have consistently rejected this title, asserting that fire instead serves as an icon, directing their thoughts towards God (Ahura Mazda), positivity and truth (𐬀𐬴𐬀 aṣ̌a) as described by their prophet. Indeed, perhaps the warm, animated and seemingly sentient nature of fire inspires veneration with greater immediacy than the static icons found in other traditions. Fire serves as a tangible embodiment of both the illuminated mind and the divine presence, symbolizing the ‘cosmic fire’ or life force in all animate things, plants, animals and men. Zoroastrian ‘eternal fires’—burning uninterruptedly since creation and consecration, sometimes for centuries or even millennia—are invested with an immense aura of sanctity among the faithful. It can be further stated that Zoroastrian liturgy places as much importance in sustaining the purity and integrity of water and the animal and plant kingdoms as it does fire. Special reverence for nature has undeniably bestowed a distinctive quality upon Zoroastrian worship, enriching its spiritual tapestry.

Zoroastrians in Shirāz observe the ancient festival of ‘Sadeh’. In ancient times, the fire was kept burning all night. The following morning, women would take a small portion of the blessed fire back into their homes to make new household fires. At the end of the year (Nowruz), remnants of the fire were returned to the eternal temple fire (c. 2020)

During the Sasanian period (226-651 A.D.), apparently three preeminent fires known as Ātaš Bahrāms (lit. “Flames of Victory”), existing since creation presumably in late Achaemenid or Parthian times, were assigned the highest grade of sanctity in the Zoroastrian religion. According to tradition, an Ātaš Bahrām is consecrated by purified embers from sixteen different sources, including the fire created by a lightning bolt. They therefore symbolized the utmost sanctity and purity, eclipsing other ritual fires (NP آتش ātaš > Avestan 𐬁𐬙𐬀𐬭𐬱 ātarš; regular MP 𐭭𐭥𐭥𐭠 ādur, whence NPآذر āḏar) in the realm, and each was in turn associated with a specific region and class of individuals. Each quarter of Iran thus had its own great fire, namely: Ādur Gušnasp in Media dedicated to warriors and nobility, Ādur Farnbāg in Pārs dedicated to the priest class, Ādur Burzēn-Mihr in Parthia dedicated to farmers, and a fourth much venerated great fire was that of Karkūy in Sistān.

After the 5th century A.D., it became customary for each Sasanian king to make a pilgrimage on foot to Ādur Gušnasp temple after his coronation at Seleucia-Ctesiphon. There, the kings lavished the temple with royal gifts, sought counsel from the priests, and received blessings from Ohrmazd through Ādur Gušnasp‘s gentle radiance. Lamentably, following the Arab-Islamic conquest of Persia, Muslims gradually extinguished sacred fires and either demolished fire temples or converted them into mosques (such as the Magok-i ʿAṭṭār Mosque in Bukhara). However, it is likely that an Ātaš Bahrām established in the Yazdi plain around the 13th century A.D. and which is now housed in the Zoroastrian Fire Temple of Yazd represents the union of two preeminent fires from Sasanian times, namely Ādur-Anāhīd from Staḵr and Ādur Farnbāg, whose embers were secretly removed from their original sanctuaries and safeguarded by priests in hiding for centuries.

History of the Role of Fire in Zoroastrianism

The religion of the prophet Zoroaster (as attested in the Gāthās 𐬔𐬁𐬚𐬁 lit. “hymns”; the oldest portion of the Avesta attributed to Zoroaster himself) was the world’s first monotheistic religion, although there remains no historical evidence pointing to the Zoroastrians’ awareness of this point. Even a hypothetical sect of the religion, Zurvanism, declared the existence of a single transcendental, neutral and passionless deity of infinite time and space that made no distinction between good and evil (Zurvān; from Avestan 𐬰𐬭𐬬𐬀𐬢 zruvan-, lit. ”time”). Zoroastrianism is thus characterized by a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic ontology and an eschatology which predicts the ultimate conquest of evil by good. Throughout history, the distinctive characteristics of Zoroastrianism, including its monotheistic nature, messianism, emphasis on free will and the notion of posthumous judgment, the concepts of heaven, hell, angels, and demons, among others, have deeply influenced Christianity, Judaism, Gnosticism, Northern Buddhism, and even Greek philosophy.

The veneration of fire within the Zoroastrian tradition can be traced to the Indo-Iranian cult of the hearth fire in Central Asia, in all probability having its origins in Indo-European times in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe (compare the analogous sacred eternal flame of Vesta in Rome, tended to by the Vestal virgins). The hearth fire, serving as a source of warmth, illumination, and solace, held profound significance for the ancient Iranians, who perceived it as a visible embodiment of the divine entity known as Ātar (Avestan 𐬁𐬙𐬀𐬭; of unknown origin). Celestial fires, present in the forms of the sun and moon, were also venerated by facing them and directing worship towards them in open-air, especially if a terrestrial fire was out of reach. This perception positioned Ātar as both the devout servant and the commanding master of humanity, reflecting an enduring reciprocal relationship. As an expression of gratitude for Ātar’s assistance, regular offerings of incense or fragrant woods and sacrificial animal fat (causing the flames to leap up) were presented through a ritual referred to as ātaš-zōhr (from Avestan 𐬁𐬙𐬀𐬭𐬱 𐬰𐬀𐬊𐬚𐬭𐬀 *ātarš-zaoθra “offering to fire”). Moreover, natural elements such as fire and water assumed a pivotal role in various religious ceremonies. The ancient Yasna Haptaŋhāiti ritual (Yasna 35–41) is believed to trace its lineage to a pre-Zoroastrian liturgical practice involving priestly acts of devotion directed towards fire and water.

Zoroaster further elevated this Indo-European cultural inheritance by associating fire to the creation of Aṣ̌a Vahišta (𐬀𐬴𐬀 𐬬𐬀𐬵𐬌𐬱𐬙𐬀 “Best Truth”; NP: ارديبهشت Ordibehešt > MP 𐭠𐭥𐭲𐭥𐭧𐭱𐭲𐭩 Ardwahišt) and recognizing it as the instrument through which God’s judgment would be executed on the Last Day. According to his teachings, a cataclysmic event, symbolized by a fiery flood of molten metal, would engulf the earth, subjecting humanity to a final judgment (referred to as Frašō-kərəti 𐬟𐬭𐬀𐬱𐬋⸱𐬐𐬆𐬭𐬆𐬙𐬌; MP: 𐭯𐭫𐭱𐭠𐭪𐭥𐭲 Frašagird ) before evil is destroyed once and for all, and the universe will be in perfect unity with Ahura Mazda. For Zoroaster, the cult of fire thus held profound moral and spiritual significance. As expressed in Yasna 43.9, he proclaimed, “I shall diligently contemplate truth (aṣ̌a) during the offering made with reverence to fire,” and he instructed his followers to always pray in high places and in the presence of fire—whether earthly fire or the celestial bodies of the sun and moon (as indicated in Mēnōg-ī xrad, chapter 53.3-5). At this early stage, it is thought that the cult of fire coexisted with other cults, particularly that of water (representing the yazāta Arədvī Sūrā Anāhitā).

The cult of terrestrial fire comprised both hearth fires and ritual fires, each serving distinct purposes. In the traditional setting, individuals would establish their own hearth fire upon founding a household, ensuring its continuous burning throughout their lifetime. This domestic fire, symbolizing perpetual warmth and vitality, held great significance for Iranian families. Notably, the Greeks also revered the hearth fire, and while Herodotus acknowledged the Persians’ deep reverence for it, he did not singularly label them as “fire-worshippers” and he made no mention of temples among them. However, in all probability during the later Achaemenid period, a Zoroastrian temple cult dedicated to fire emerged. This development, possibly instigated by the orthodox faction, served as a response to the introduction of temple cults with statues of Anāhīta.

The temple cult of fire, an extension of the domestic fire cult, involved a sacred fire enthroned on an altar-like stand (ātašdān; these were traditionally hewn of stone until the 19th century, when the Parsi community took to putting their sacred fires in big metal vases made of brass or German silver, which they then introduced to their coreligionists in Iran). It retained the traditional wood fire and continued to receive prescribed offerings five times a day, meticulously administered by a priest who safeguarded its purity. Details about the classification and constitution of sacred fires during the Achaemenid period are scant. Nevertheless, it is plausible that the temple cult was instituted with utmost grandeur and dignity, aiming to rival the majestic image-cult of Anāhīta. Consequently, the most revered type of sacred fire (Ātaš Bahrām) likely traces its origins to the earliest periods. According to a post-Sasanian tradition, this fire is created by combining purified embers from numerous fires, including lightning fire, in an elaborate consecration ritual. Once consecrated, the sacred fire is ceremoniously carried in procession to its sanctuary, a triumphant act known as pad wahrāmīh “towards victory”. Accompanying priests brandish swords and maces, and upon completion of the ceremony, some of these weapons are hung on the sanctuary walls, symbolizing the fiery entity’s warrior nature and its unwavering battle against all forces opposed to truth (aṣ̌a).

The temple site offers a view of what was called Zendān-e Solaymān since Mongol times; it is a cone-shaped hollow mountain built up of limestone during millions of years by a hot spring underneath. The mountain is 97 to 107 meters tall while its crater is 65 meters wide and around 80 meters deep. The crater was at one time full of water, fed by floor springs, but it dried centuries ago. Shīz, Iran

Ādur Gušnasp Fire Temple

The historical knowledge of Ādur Gušnasp surpasses that of the other two prominent fires, namely Ādur Farnbāg and Ādur Burzēn-Mihr, due to two key factors. Firstly, its temple in Azerbaijan was located near the western border of Iran, attracting the attention of numerous foreign visitors. Secondly, the Sasanian kings showed favor towards it starting from the early 5th century. As a result, it received frequent mentions in the later part of the royal chronicle, known as the Xwadāy-nāmag, and in the Šāh-nāma, where it was also referred to as Āḏar-Ābādagān (>”Azerbaijan”). Although the exact original location of Ādur Gušnasp remains uncertain, it appears that it was relocated to a remarkably beautiful site in Azerbaijan, known as Taḵt-e Solaymān during Islamic times, but likely called Mount Asnāvand by the Median magi. This site features a hill of mineral deposits formed by a spring within it, creating a picturesque lake atop the hill that is elevated above the surrounding landscape. A new temple was constructed for Ādur Gušnasp at this location, and its association with the Sasanian royalty was emphasized to the extent that it became customary for each king, following their coronation, to embark on a pilgrimage to the temple on foot (although accounts in the Šāh-nāma suggest that the monarch only walked from the base of the hill as a gesture of deep reverence). The shrine received generous offerings from the kings, and a legend developed claiming that the first monarch to enrich it was Kay Ḵosrow himself, who sought divine assistance against Afrāsīāb while praying at the temple alongside his grandfather Kāvūs.

(1) A recently restored fire temple (ātaškada) known as Qal’a-i Mugh, with a symbolic fire established on the fire-altar, near Istaravshan in the Sughd region, Tajikistan (2019). The structure features characteristic Zoroastrian architectural vocabulary and exterior decorations from Sasanian times, including a domed sanctuary (gombad) with intricate brickwork surrounded by a courtyard (2) The baked brick fire-altar (ātašdān) has a traditional three-step pedestal and long shaft decorated with recessed panels. Ātašdāns holding preeminent fires were historically hewn of solid blocks of stone, with lower-grade fires frequently held in mud-brick altars. However, they were replaced by metal vases per a Parsi trend in the 19th century

There are several references in the epic mentioning visits by Bahrām V (421-39 A.D.) to the fire temple. It is said that he spent the Nowrūz and Sadeh festivals there and, on another occasion, entrusted an Indian princess, his bride, to the high priest of the temple for conversion to the Zoroastrian faith. According to Ṯaʿālebī, upon Bahrām’s return from his campaign against the Turks, he offered the ḵāqān’s crown to the shrine and dedicated his wife and her slaves as servitors. Ḵosrow Anōšīravān is also said to have visited Ādur Gušnasp before embarking on a military campaign. Later, he bestowed a substantial amount of treasure from tribute received from Byzantium on the fire temple. Ḵosrow Parvēz prayed at Ādur Gušnasp for victory in battle and subsequently offered a generous portion of the spoils to the sanctuary. It was not only the kings who made petitions and offerings at the temple, as evidenced by a prescription in the Bundahišn, which states that those praying for the restoration of eyesight should vow to send a golden eye to Ādur Gušnasp, or those seeking an intelligent and wise child should send a gift to the temple.

The grandeur of the ruins of Ādur Gušnasp aligns with the accounts found in literary records and exceeds that of any surviving Zoroastrian place of worship. To safeguard the sanctuary, the hilltop was enclosed by an immensely thick mud-brick wall. Later, during the Sasanian period, a stone wall measuring 50 feet in height and 10 feet in thickness was erected along the rim of the hill, featuring thirty-eight towers at regular intervals. The temple precinct itself was surrounded on three sides by an additional wall, while the south side remained open to the lake. Extensive excavations have unveiled the layout of this grand complex. Approaching from the north, one would enter a spacious courtyard suitable for accommodating numerous pilgrims. From there, a processional path led towards the lake, featuring a square, domed room that faced north and south. This lavishly adorned room possibly served as a space for prayer and ceremonial ablutions, culminating in a large open portico that offered a lovely view of the waters. A covered pathway extended along the front of the building, leading to a remarkable sequence of pillared halls and antechambers that stretched from south to north on the western side of the processional way. It is believed that the sanctuary of Ādur Gušnasp itself occupied the northernmost end of these halls. Initially, the sanctuary took the form of a flat-roofed, pillared structure made of mud-brick, but it was later replaced by a stone construction with a domed roof. The walls of this sanctuary were adorned with a prominent stucco frieze in high relief, and judging by the elaborate Sasanian-era decorations found at the fire temple at Kūh-e Xwāja in Sistān, may have once featured an intricate scheme of paintings and bas reliefs. Beneath the dome, archaeologists discovered a three-stepped pedestal for a grand fire-altar (ātašdān) made of stone and the base of its cylindrical shaft. Fragments of smaller altars and ritual vessels have been unearthed within and near the pillared halls that led to the sanctuary, indicating the ongoing devotional activities, including offerings, prayers, and religious ceremonies.

The vast temple complex included numerous additional rooms, such as smaller shrines and the temple treasury, which likely held valuable and priceless offerings. Objects that can be precisely dated have not been found in the ruins prior to the reign of Pērōz (A.D. 457-84). However, a room near the main entrance yielded a collection of over 200 clay sealings, including eighteen inscribed with the title “high-priest of the house of the fire of Gušnasp” (mowbed ī xānag ī Ādur ī Gušnasp). In A.D. 623, during his campaigns against Ḵosrow Parvēz, the Byzantine emperor Heraclius sacked the temple of Ādur Gušnasp, destroying its altars, setting fire to the entire structure, and mercilessly killing all living beings present. Nevertheless, the great fire itself was evidently rescued and later reinstated. The destruction of Ādur Gušnasp‘s shrine may be alluded to in a pseudo-prophecy found in the Persian Zand ī Vahman Yašt, which predicts the removal of Ādur Gušnasp from its original location due to the devastation caused by the invading armies, implying its relocation to Padašxwārgar. After being reinstated in its temple on the hill, Ādur Gušnasp continued to burn for many generations following the arrival of Islam. However, the temple faced increasing persecution, and the great fire was likely extinguished by the end of the 10th century or, at the latest, the early 11th century A.D. The ruins of the temple were subsequently utilized as a quarry for constructing a palace on the hilltop for a local Mongol ruler.