Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This article surveys the Manichaean religion which was founded in Sasanian Persia in the 3rd century AD but quickly expanded into the Roman Empire and Inner Asia, with a pocket surviving in Fujian, China into modern times

The only extant statue of the Iranian prophet Māni (摩尼 Móní), carved into a cliff at the Cǎo’ān nunnery (photo 3) in 1339 A.D. by Chinese Manichaeans during the Yuan Dynasty, Jinjiang, Fujian province, China. In China, Māni assumed the configuration of “Māni, Buddha of Light,” depicted with straight hair draped over his shoulders and sporting a beard in a Chinese Manichaean icon from the 14th or 15th century A.D. (photo 2) The distinctive features of the prophet (arched eyebrows, fleshy jowls) are still apparent in the carving. By report, the statue had a mustache and sideburns, but they were removed by a 20th-century Buddhist monk trying to make the statue more like a traditional Buddha. UNESCO designated the site of the Manichean Cǎo’ān a World Heritage Site in 1991 as a unique relic of an extinct world religion.

Background

Māni (216–274 CE) was an Iranian prophet born near the Sasanian Persian capital, Ctesiphon, who reported having received two revelations, the first at the age of twelve and the second at twenty-four, from a spiritual being whom he later designated as his heavenly “Twin” (Greek: σύζυγος súzugos “yokefellow”; Aramaic: תאומא tɑʔwmɑ “twin”). Following successive revelations by Zoroaster, Buddha, and Jesus Christ—the three ‘Apostles of Light’—Māni stylized himself as the ‘final seal’ (or παράκλητος Paráklētos ‘Paraclete of Truth’) in a line of prophets whose respective religions had come to predominate in the great cultural spheres of Rome, Persia and China. This self-understanding was shaped within the religiously plural environment of Sasanian Persia, where all three traditions were already widely practiced. Moreover, Māni was in turn born into a noble Parthian family affiliated with the Jewish Christian sect of the Elkasaites in Asōristān (Sasanian Mesopotamia), a milieu whose heterodox character provided fertile ground for the synthesis and universal claims of his later teaching.

In essence, Māni’s message calls upon the faithful to liberate the divine light that is imprisoned in matter so that it may return to the realm of pure spirit (the World of Light). Salvation is thus understood to depend upon spiritual knowledge and progressive purification from material attachments, since the physical world itself is held to be intrinsically evil. The prophet himself is credited with the composition of a substantial corpus of sacred writings. Seven works were written in Syriac—a liturgical Aramaic language understood in Asōristān—while a further treatise, composed in Middle Persian for King Shapur I, set out the principles of the religion and was known as the Šābuhragān (Chinese: 二宗经 Èrzōng jīng). Māni was also a famed painter who disseminated his teachings through illuminated picture books, above all the Aržang (New Persian: ارژنگ; Coptic: ⲉⲓⲕⲱⲛ Eikōn; Parthian: dō bunɣāhīg), as well as through hymns of praise and dramatic performances, employing a range of media to convey his message.

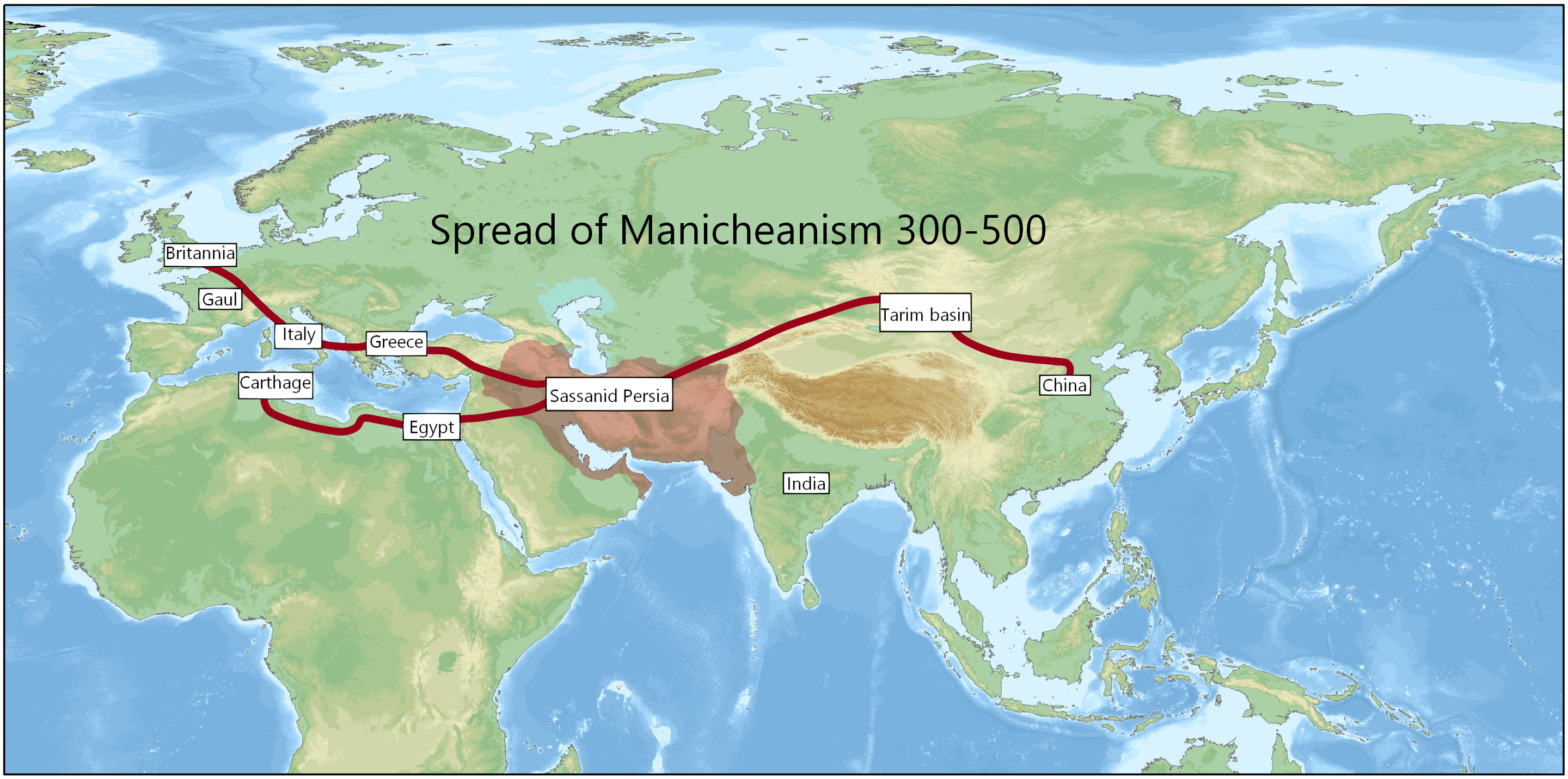

Manichaeism has aptly been described as ‘the only world religion in the true sense.’ Māni envisioned his teaching as a universal creed intended to encompass the whole of the known world, to embrace and surpass all previous religious traditions, and to explain all that exists in heaven and on earth. Owing to its zealously missionary character, within a mere two centuries this highly mythologized, universalist, dualistic, vegetarian doctrine had won adherents across a vast geographical range, extending from Hispania, Gaul, Rome, and Numidia, through Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and Transoxiana, as far as China, where it has endured in an altered form into modern times. It is evident that, as the religion spread, distinct regional expressions emerged–commonly designated as ‘Chinese’, ‘Roman’, or ‘Egyptian’ Manichaeism–yet in its early centuries these were held together by an overarching ecclesiastical structure. This was centred upon the Holy See of Babylon at Ctesiphon and governed by the office of the Archegos (ἀρχηγός), which exercised authority over the far-flung communities of the faith.

Whilst the entirety of the existing Manichaean corpus was recovered fragmentarily in Egypt and China in the 20th century, this speaks naught to the the religion’s historical distribution or popularity elsewhere. Indeed, Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD) was a Manichee prior to his conversion to Christianity, which followed a disillusioning experience with Faustus of Mileve, a fellow Numidian and a prominent Manichaean teacher active in Carthage. At the opposite chronological end of the tradition, the last recorded Archegos resident at Ctesiphon, known to the Muslims as Abū Hilāl al-Dayhūri (r. 754–775 AD), was likewise of North African extraction. Further testimony points to a substantial Manichaean presence in the Latin West. Hilary of Poitiers wrote that Manichaeism was a significant force in Roman Gaul by 354 A.D, while numerous Manichaean monasteries existed in Rome in 312 AD during the time of Pope Miltiades. In Central Asia the religion attained an even more striking degree of political recognition, when the Uyghur Khaghanate, under the influence of its Sogdian urban elites, adopted Manichaeism as its official faith between 763 and 840 CE.

Yet despite this remarkable geographical spread and occasional institutional support, Manichaeism stands almost alone among the major organized religions of the pre-modern world in having suffered a near-total extinction. Subjected over the centuries to sustained and often severe persecution across the regions in which it had once flourished, it ultimately survived only in scattered remnants, preserved by chance and circumstance rather than by continuous tradition.

(1) Phases of Manichaean history (3rd-17th centuries A.D.) (2) The spread of Manichaeism (~300-500 A.D.)

Manichaean Cosmogony, Social Organization and Ethics

Māni’s teaching, which is essentially Gnostic in character, sets forth a fantastically detailed system of divine and demonic forces. Setting aside the syncretic elements of his religion and considering notions unique to Manichaeism, the following may be enumerated. The Manichaean narrative begins with a primordial cosmological battle between two independent and eternal ‘realms’ or ‘natures’, existing beyond the bounds of the physical universe: the World of Light and the World of Darkness. The conflict between these two intangible realms composed of the substances Light (Spirit) and Darkness (Matter), respectively, continues to define all of reality.

The drama unfolds when the demonic powers of Darkness, driven by greed, launched an assault upon the World of Light, whereupon God, the Father of Greatness, summons forth divine emanations of himself to defend his realm. However, in the course of the ensuing combat, the two substances became disastrously intermixed at the hands of merciless demons. Then, a second set of Light divinities were summoned, who created the world, sun, moon and stars as an intricate mechanism designed to effect the separation of the two substances. But demons retaliated to this tactic by further dividing the imprisoned Light still more finely and dispersing it throughout the material constituents of Earth. Thus human beings, animals, plants, water, soil and other features of the visible world are understood to be sparks of Light trapped in the illusion of matter, causing the Light particles to become defiled by the Darkness encapsulating them. Therefore, the Manichaean view explained the existence of evil by positing a flawed creation in the formation of which God took no part, and which constituted rather the product of an attack by evil beings against God. The appearance of the Prophet Māni is accordingly interpreted as a further intervention by the World of Light to reveal to mankind the true source of the spiritual Light imprisoned within their material bodies.

Perhaps owing to their ‘inferior’ intellect (since mental activity was understood as a manifestation of Light), animals other than humans were viewed as the abortions of she-demons and therefore were particularly rich in Dark substance. Plants, by contrast, and in particular melons, cucumbers, grapes, and other vegetables and fruits distinguished by a marked luminescence, were believed to contain high concentrations of Light particles, which might be liberated through the digestive processes of the Elect, as will be described below.

Thus, man’s charge was conceived as twofold in its support of the World of Light and its struggling, non-omnipotent God. First, adherence was required to the rules and observances of the Manichaean Church, including the embodiment of the virtues of Light (Spirit), among them patience, honesty, non-injury, joy, kindly speech, temperance, wisdom, vegetarianism, and charity. It is noteworthy that within this ethical framework no specific commandments are articulated concerning gender roles or sexual orientation, either for lay-followers or for the priesthood—a silence which permits an interpretation of Māni’s teaching that recalls, in this respect, the ethical universality characteristic of Zoroaster’s own utterances in the Gāthās. Secondly, the ascetic elite, designated the “Elect”, were entrusted with the task of liberating dispersed Light from its entrapment in demonic matter, most notably in vegetables, fruits, and grains, thereby assisting its return to the World of Light. This ascent was believed to proceed by way of the two heavenly “ships” or “storehouses”, the sun and the moon, whose waxing and waning marked the movement of Light prior to its passage onward through the Milky Way. In this way, Manichaeism articulated a vision of the cosmos in which Light was believed to be trapped within the world, and its adherents were expected to live as though that belief were literally true.

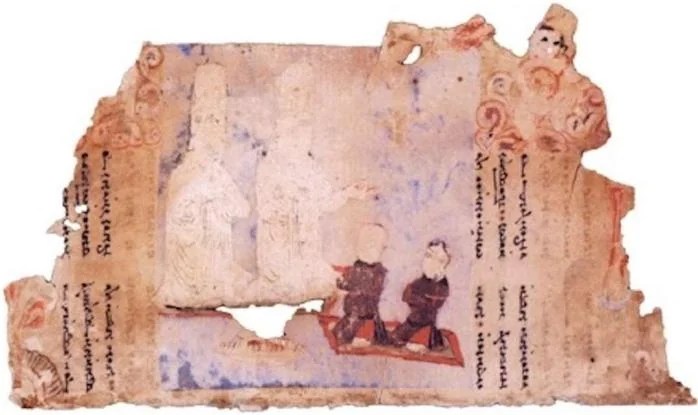

An artistic restoration of ‘The Work of the Religion Scene’ (MIK III 4794 recto, detail), from an illuminated manuscript of the Aržang, or Māni’s ‘Book of Pictures, recovered near Turfan, China. The composition functions as a didactic diagram illustrating the central aim of Manichaean practice: the liberation of Light from its captivity in Darkness. Lay-followers are shown offering vegetarian food , believed to contain a high concentration of Light particles, to the Elect, whose consumption of this nourishment effects the release of the imprisoned Light. Through the chanting of hymns, the freed light is depicted as departing from the bodies of the Elect and ascending toward the World of Light. The moon and the sun function as vessels of Light, conveying the freed particles back to God, while above the scene the Father of Greatness, symbolized by his right hand, reaches down to receive the shipment

Manichaean social organization divided the faithful into two classes: the “Elect”, an elite body of monks committed to itinerant missionary activity and a life of monastic asceticism, and the “Hearers”, lay-followers who continued to lead relatively ordinary lives. The relationship between the two was conceived as reciprocal, for the Elect were sustained by the material support of the Hearers, while the latter assumed responsibility for actions—such as procreation and the cultivation of crops—which were believed to propagate matter and so to further the dispersal of Light. The Hearers, in turn, depended upon the spiritual salvation effected by the chaste, vegetarian, and indigent manner of life of the Elect, who were required to observe scrupulously twelve ethical commandments in order to purify their bodies as instruments for the liberation of Light. The Elect, “sealed” with the three seals of mouth, hands, and breast—by which purity of speech, action, and feeling was ensured—lived in monasteries, yet also went forth on foot to spread and strengthen the faith, observing a discipline by which they took a vegetarian meal only once daily, after nightfall.

Since neither community was regarded as wholly capable of fulfilling all its respective religious obligations, regular rites of atonement were observed, in the form of confession (xwāstwānīft in Parthian), which were performed on Sundays for the Hearers and on Mondays for the Elect. Hearers who lived righteously were believed capable of reincarnation as Elect, or perhaps as fruit, which could be redeemed through consumption by the Elect, while the souls of the Elect themselves, disentangled from the darkness that had encased them, were held to return, at death, to the World of Light. Jesus Christ, regarded as Māni’s forerunner and as the apostle whose mission he continued, was held to serve as the “guiding deity” who received the light-bodies of the righteous upon their deliverance.

Icon of the King Jesus; a digital reconstruction of the enthroned Jesus (光明夷數 Guāngmíng yí shù ‘Jesus of Light’) image on a Manichaean temple banner from ca. 10th-century Gāochāng, China. It is the oldest known Manichean Jesus portrait.

Moreover, the Hearers were expected to provide alms of vegetarian food to the Elect, for it was believed that within melons, gourds, grapes, fruit-juices, and similar substances Light particles lay imprisoned, to be liberated through the miraculous purifying instrument of the Elect’s digestive tracts. During the daily meal ceremony, the digestive processes of the Elect served as ‘altars’ upon which food was offered and ‘burned’, followed by sequences of prayers and songs of praise for the ascension of freed Light back to the World of Light. The alimentation rituals were elaborated during the ‘Throne festival’ (Greekbēma; Mid. Pers. and Parthian: gāhrōšn “Throne of Light”)—held on the final day of the Manichaean fasting month—when a large portrait of Māni himself (Greek eikṓn, Mid. Pers. pahikirb) would be positioned on a splendidly adorned ‘throne’ at the head of the meal ceremony.

(1) Sacrificial ceremony for the 1013 birthday of Lín Dèng (林瞪; 1003-1059 A.D.), an important Chinese Manichaean leader who lived during the Northern Song Dynasty in Băiyáng township, Xiápǔ county, Fujian province, China. Today in Băiyáng Township, the “Xiápǔ Manichaean manuscripts” are used for rituals conducted for Lín Dèng in the three villages of Băiyáng 柏洋村, Shàngwàn 上万村, and Tǎhòu 塔后村 (2) Master Chen Peisheng officiates prayer scene at Puxi Fushou Palace (福寿宫), Fuzhou, China. (3) A Yuan-era black glazed bowl found at the Cǎo’ān Temple excavation with the engraving on the bottom “Church of Light” (明教會 Míng Jiàohuì), a name for the Manichaean faith known in China as 明教 Míngjiào “Religion of Light”

Syncretism in the Cases of Egypt and China

The remarkable degree of syncretism present in Māni’s teachings allowed local beliefs to be seamlessly woven into the fabric of his own unique notions. By a process loosely analogous to molecular mimicry in venereology, contrived similarities between Manichaean teachings and native beliefs occasioned the rapid comprehension and adoption of his religion by converts. Names for Māni’s religious concepts and mythological actors were often substituted for names drawn from the local religion, while prayers, hymns, and other forms of worship were in many cases adopted wholesale with little variation. Thus Abbā dəRabbūṯā (“Father of Greatness”, the highest Manichaean deity of Light), in Middle Persian texts might either be translated literally as pīd ī wuzurgīh, or substituted with the name of the deity Zurwān, from the Zurvanist branch of Zoroastrianism. The names Māni had assigned to the gods of his religion show identification with those of the Zoroastrian pantheon, even though some divine beings he incorporates are non-Iranian. For example, Jesus, Adam or Eve were, respectively, given the names Xradesahr, Gehmurd or Murdiyānag. Similarly, the Manichaean primal figure Nāšā Qaḏmāyā “The Original Man” was rendered Ohrmazd Bay, after the Zoroastrian god Ohrmazd. Because of these familiar names, Manichaeism did not feel completely foreign to the Zoroastrians in Mesopotamia, Persia and Transoxiana.

This process continued in Manichaeism’s meeting with Chinese Buddhism, where, for example, the original Aramaic קריא qaryā (the “call” from the World of Light to those seeking rescue from the World of Darkness), becomes identified in the Chinese scriptures with Guanyin 觀音 (Avalokiteśvara; lit. “watching/perceiving sounds [of the world]), the bodhisattva of Compassion. During and after the 14th century, some Chinese Manichaeans involved themselves with the Pure Land school of Mahayana Buddhism in southern China. Those Manichaeans practiced their rituals so closely alongside the Mahayana Buddhists that over the years the two sects became indistinguishable. The Cǎo’ān temple in Fujian stands as an example this synthesis, as a statue of the “Buddha of Light” is thought to be a representation of the prophet Māni.

(1) 10th-century Manichaean Electae (women), discovered at the capital of the Uyghur Khaghanate, Gāochāng 高昌 (قۇچۇ Qocho; قاراغوجا Qara-Khoja), Turfan oasis, China (photos 2-3) The ruins of Gāochāng, designated the capital of the Uyghur Khaghanate in 850 A.D., Turfan, China

According to Chinese adherents of Manichaeism during the Ming dynasty, their religious tradition made its way into China via Mōzak during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of Tang (650–683 AD). Bishop Mihr-Ohrmazd, a disciple of Mōzak, followed his mentor into China and was granted an audience with Wu Zetian, who wielded significant power during the Tang dynasty from 684 to 690 AD and ruled as the emperor of the Wu Zhou dynasty from 690 to 705 AD. According to later Buddhist sources, during this audience, he presented the Šābuhragān (Chinese: 二宗经 Èrzōng jīng), which apparently became the most popular text among Chinese Manichaeans. In 731 AD, Emperor Xuanzong sought a summary of their foreign religious beliefs from a Manichaean, resulting in the creation of a text known as the “Compendium of the Teachings of Māni, the Awakened One of Light.” This text interprets the prophet Māni as an incarnation of Laozi.

Egypt was evangelized in Māni’s lifetime by his early disciple Adda who arrived in Alexandria, according to Manichaean narratives recovered at Turfan in China. Lower Egypt served as an early transit for the faith into the Roman Empire, from which it spread to Carthage and Western Europe. However, Upper Egypt in particular has been seen as a Manichaean stronghold. In the remote Kellis Oasis in Upper Egypt, Manichean psalms to Jesus were discovered that bear almost the exact formula of a Christian psalm, praising Jesus in every stanza, until the very final words: ‘Glory and victory to our Lord, our Light, Mani and his holy Elect’ (Psalmbook 52). This inherent flexibility likely facilitated its widespread acceptance across various milieus by permitting the harmonization of its teachings with pre-existing religious beliefs. On many occasions, Manichaeans were confused for by the remarkable ability to camouflage at a moment’s notice. Paradoxically, however, this malleability may have contributed to the eventual evaporation of Manichaeism, akin to sand slipping through fingers, as adherents may have found it effortless to revert to the majority religion when the need for spiritual conformity arose. In times of persecution, layers of Manichaean-specific doctrines could be relinquished without the necessity of renouncing the majority faith in its entirety.

The ruins of Kellis, Egypt. The oases of Upper Egypt once served as a stronghold of Manichaeism, with much of the the current Manichaean corpus being recovered from 20th-century expeditions there

Pingback: An Etymology of the Sogdian Title “Afšīn” – borderlessblogger