Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. The goal of this article is to introduce the reader to the history, language and culture of the autochthonous Tajik Persian-speaking population of Uzbekistan.

The anterior façade of Madrasa-i Mīr-i ‘Arab (c. 1535 A.D.) from the vantage point of the portal to Masjid-i Kalon, together part of the Po-i Kalon complex; Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

اگر آن ترک شيرازى بدست آرد دل ما را، به خال هندويش بخشم سمرقند و بخارارا

“If only that Shirâzian maiden would deign to take my heart within her hand,

I’ll donate Samarkand and Bukhara, for her Hindu beauty mole”

-Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī, Ghazaliāt

Background

Northern Tajik, a dialect of Persian, is the mother tongue of the majority of people born in the Samarqand and Bukhara oases located in the modern-day Republic of Uzbekistan. Multiple experts, international commentators, as well as Tajiks within and outside of the republic suggest that there may be between nine and ten million Tajiks in Uzbekistan, constituting 30% of the republic’s 33 million population, rather than the government’s official figure of 5%. Mainstream English sources, however, are mute on this matter.

Astonishingly, until quite recently many reputed web-based sources and encyclopedias erroneously reported that Persian had functionally vanished from those oases several centuries ago–the equivalent of disseminating the idea that Catalan and its dialects have not been spoken along the eastern shoreline of the Iberian Peninsula since the reign of House of Aragón. On the contrary, Bahodir, a local 52-year-old Uzbek man from Hokimullomir who learned to speak in Tajik in Bukhara, reports:

In Bukhara you have to speak Tajik. If you want anything to be done, it is far better. Everything gets done quicker if you speak Tajik with them. Like I told you, we lived in Bukhara for many years. Back then, at home, we spoke Uzbek, but outside we spoke Tajik. ( Peter Finke, “Variations on Uzbek Identity”. Pg 82)

Another informant, manager at a popular Samarqandian restaurant in Brooklyn, NY, told this author (translated from Persian):

Samarqand and Bukhara are Tajik-speaking cities. The majority of Uzbeks in New York City hail from Samarqand and Bukhara, and have been labeled as “Uzbeks” in our nationality, but we are in fact Tajiks.

The reasons for this perplexing discrepancy are manifold. On the one hand, official census statistics released by the Uzbek government reflect the continuation of a well-documented Soviet-era effort to trivialize the Tajik population of Central Asia. Indeed, it is hard to deny that there is some truth in this, in light of the rather arbitrary territories assigned respectively to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan S.S.R.’s in the 1920s. Those assigned to the latter were primarily mountainous hinterlands; sparsely inhabited by speakers of various Eastern Iranian languages rather than Persian dialects. Fueled by fears of the more sedentary and more literate Tajik population posing potential resistance to Soviet rule, as well as the possible geopolitical linkage with Iran, in 1929 the areas of modern-day Tajikistan were split off to form the Tajik SSR, but the Uzbek SSR retained the traditionally Tajik-speaking regions of Samarkand, Bukhara, and parts of the Ferghana Valley. In order to make the borders look plausible, authorities forced the majority of Persian speakers in cities such as Bukhara and Samarkand to register as Uzbeks (Allworth 1990; Subtelny 1994). Many Tajik intellectuals continue to assert that the cities of Bukhara and Samarkand, which were (and are) predominantly Tajik-speaking, should have been assigned to Tajikistan (Atkin 1994; Foltz 1996). Of note, in 2009, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon reportedly told journalists that he had threatened Uzbek President Islam Karimov that he would “take Samarkand and Bukhara back.”

Second, and closely connected with the ideas about ethnogensis, is the fate of the concept of Uzbekness during the period of national delimitation. The process of creating the Uzbek natsional’nost’ (националъностъ “nationality”) in early Soviet times has been regarded as the most artificial in the region and as a deliberate act on the part of the authorities with little justification in pre-existing patterns of identity (although the name “Uzbek” had existed before to refer to the 16th century Qipchaq-speaking tribal confederation led by Shaybani Khan, it had been used for self-designation by only a fraction of the ancestors of the present day population, who instead used terms such as “Turki” and “Sart”, yet more commonly identified with their city rather than language).

On the other hand, in most contexts Tajik-speakers in Uzbekistan prefer not to differentiate themselves from the so-called Uzbeks, and consequently lump themselves together with them as a distinct entity from the citizens of neighboring Tajikistan who are– secondary to decades of strained relations and economic instability–the subject of negative public opinion. As nearly all Tajik-speakers in Uzbekistan are functionally bilingual in both Tajik Persian and Uzbek, identification with the titular nationality affords Tajik-speaking citizens social prestige and heightened prospects for social and economic mobility. Cases where brothers ended up with different ethnicities have been reported for Bukhara in particular (Naby 1993). Despite their decided indifference in matters of national identity, the Tajik-speakers of Uzbekistan continue to safeguard their distinct language which is often referred to colloquially as Forscha (“Persian”), Tojikcha (“Tajik”), Bukhorocha and Samarqandcha, and several informants recall the scorn of their elders imploring them as children to “not speak Turki.” As such, Northern Tajik will likely survive in Uzbekistan, however with governmental pressure its domain of use is becoming increasingly restricted to the domestic sphere. Of note there are, however, a minority of Tajiks in Uzbekistan who identify foremost as Tajiks and are active in local spheres of television broadcast, music, and other cultural activities.

Samarqand-based television program “Shomi Samarqand” is one of several regional programs that are broadcasted in the Tajik-Persian language within Uzbekistan

By law, Uzbek is Uzbekistan’s exclusive nation-wide state language. Government policy requires the use of Uzbek in all dealings with officials, in street signage, and in business and education. Russian is still spoken widely and boasts widespread prestige, however, and as in other post-Soviet states enjoys ambiguous legal status as “the language of interethnic communication.”

Paradoxically, in the autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan (Qoraqalpogʻiston Respublikasi) located in ancient Khwarezm, Karakalpak (a Kipchak Turkic language closely related to Kazakh, brought by nomadic migrants to that region in the 18th century) enjoys official status alongside Uzbek, even though numerically there are estimated to be at least twelve times as many Tajiks as there are Karakalpaks within Uzbekistan.

Bukhara Oasis

In linguistic and ethnic terms, the city of Bukhara is still renowned for its Tajikness, and outside the region sometimes everyone originating from there is depicted as Tajik. Foltz believes 90 percent of the population of Bukhara city to be Tajiks (1996:213). According to Finke, the ubiquity of Tajik is obvious to the most casual observer. Even in social situations among strangers, such as on buses or talking on the phone, Tajik is spoken. Many Uzbeks report learning or improving their Tajik after moving to town. In addition, in contrast to many official reports, Tajik is also spoken in many of the rural areas, particularly in the north and west of the Bukhara oasis. It may also be worth noting that Bukharan Tajik enjoys some prestige in Bukhara province as the language of city dwellers. Not surprisingly, the oft-quoted aphorism associated with the city is a Tajik-language quote originating with the Naqshbandi Sufi order which was founded in Bukhara: “Дил ба ёр у даст ба кор” dil ba yor u dast ba kor “One should devote their heart to God and their hands to the production of crafts.”

Khorezmian-Uzbek pop artist Feruza Jumaniyozova performs a folk medley in the local Bukharian Tajik language in Bukhara. Many Uzbek national singers perform songs in Tajik Persian which they devote to their fans in Samarqand and Bukhara regions

Virtually every Bukharan Tajik speaker is bilingual in Tajik Persian and Uzbek, the heavily Persianized Turkic language with which Tajik has been in intensive contact for centuries. Within Bukhara, the Uzbek language is spoken with a decidedly Tajik character (i.e. pronunciation of man, san instead of standard men, sen for the 1st and 2nd person singular pronouns; preferences for Persian-style subordinate clauses using the Persian article ki ). Language mixing, i.e. code switching and code mixing, takes place even in households where every member is a native speaker of Bukharan Tajik. However, Tajik–Uzbek bilingualism is not limited to those who have Bukharan Tajik as their first language – native Uzbek speakers who grow up in the city of Bukhara usually acquire some command of Bukharan Tajik, which they utilize either passively or actively. Among Uzbeks, Tajik (Persian) is often idealized as shirin or “sweet”, and proficiency in Tajik language, music and literature remains, much like centuries in the past, a desirable skill.

The autochthonous people of the Bukhara oasis are Tajik-speaking, including the once sizable Jewish community that still boasts several hundred souls within the city today. Despite popularization of Bukhoric as a distinctively “Jewish language” by migrants to the West, there exist few if any tangible differences between the Tajik vernacular of the Jews and Muslims in Uzbekistan, save terminology for Jewish religious concepts and rites which are borrowed from Hebrew and Aramaic. The language of Bukharian Jews therefore does not constitute a true sociolect, and is better understood simply as Northern Tajik.

The city of Bukhara is renowned as a historic center of silk and cotton textile production (atlas and adras), a craft that has its origin in the material culture of the autochthonous Tajik population. Known in the West as “ikat”, abrabandi is the art of resist-dyed warped silk, rendering bold, abstract motifs that is often used in garments and upholstery. In abrabandi (literally “binding of clouds” in Persian, referring to the fuzzy appearance of the patterns), the master pattern of the atlas textile is determined by the nishonzan (“one who sets the marks” in Persian), and the silkworms cocoons are carefully processed in the pillakashkhona (Persian for “workshop where cocoon is pulled”). Following the charcoal marks of nishonzan, the abraband (“binder of clouds”) carefully prepares the warps for the next skillful master, the rangrēz, or “dyer.” In Bukhara, the blue and indigo rangrēz were traditionally Jews. The warps are then carefully placed on a wooden loom and hand-woven into a finished textile. Evidently, despite becoming popularized throughout the country and the world as a quintessentially “Uzbek” craft, this complex art and its technical terminology has its roots in the indigenous Tajik-speaking Muslim and Jewish urban population of Transoxiana rather than the more recent Turkic migrants.

Abrabandi, or “binding of clouds” in Persian, is a magnificent resist-dyed silk textile produced in Bukhara.

A traditional abrabandi kaftan from Bukhara, early 20th century.

“Bukharan Bureaucrat” (c. 1905) by the Russian photographer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii, who used a special color photography process to create a visual record of the Russian Empire in the early 20th century. The bureaucrat is pictured vested in a splendid abrabandi kaftan of local production.

Samarqand Oasis

The prominence of Tajik in Samarqand, located just 30 kilometers from the border of the neighboring post-Soviet Republic of Tajikistan, is not dissimilar to the situation in Bukhara. According to Richard Foltz, Tajiks account for perhaps 70 percent of the population of Samarqand. Much like in Bukhara, Northern Tajik (Persian) is the primary vernacular heard in the streets, markets, and domestic sphere, and the city is home to many renowned local Tajik-language singers such as Daler Xonzoda, Sherzod Uzoqov, Rohila Olmasova, Ruslan Raxmonov, and Baxtiyor Mavlonov, among others. Local crafts for which Samarkand is famed, such as the Samarqand style of zarduzi or golden-thread embroidery, take their technical terminology from Tajik Persian. As a famous epithet uttered by locals goes,

Tajik Persian: Самарқанд сайқали рўйи замин аст, Бухоро қуввати ислом дин аст

Persian (Iran): سمرقند صیقل روی زمین است، بخارا قوت اسلام و دین است

English: “Samarkand is the gem of the earth, Bukhara is the powerhouse of faith”

There exist a number of local radio and television broadcasts in Tajik Persian, such as the Shomi Samarqand television program which covers local festivals, arts, crafts and other civil activities. The local Tajik Persian newspaper Ovozi Samarkand (“Voice of Samarkand”) publishes twice weekly, but it appears to be absent in other parts of the country. Traditional Tajik maqom ensemble pieces abound in the local music culture, including the renowned Ushoqi Samarqand:

Tajik Persian: Биё ки зулфи каҷу, чашми сурмасо инҷост; Нигоҳи гарм у адоҳои дилрабо инҷост (biyo ki zulfi kaj u čašmi surmaso injost; nigohi garm u adohoi dilrabo injost)

English: “Come! The lover’s curly locks of hair and kohl adorned-eyes are here; her warm gaze and her enchanting coquetry is here.”

While Tajik remained the language of choice for many Samarqand residents during the Soviet era, migration and state policy are steadily changing the city’s linguistic landscape. These days, there are hardly any signs written in Tajik, and there are limited opportunities for residents to educate their children or access media in their mother tongue, local Tajiks complain. Official figures for Tajik-language education in Samarqand and the surrounding region are not available, but an overall countrywide trend shows that the number of schools in minority languages is declining: There were 282 Tajik and mixed Tajik-Uzbek schools in Uzbekistan in 2004, down from 318 in 2001, according to the Moscow-based Federal Center for Educational Legislation.

Zarduzi or gold-thread embroidery is a delicate craft passed down from masters to apprentices in guilds throughout Samarkand.

According to local lore, Masjid-i Bibi Khanym (c. 1404 A.D.) in Samarqand was commissioned by Timur’s favorite wife, Bibi Khanym, in honor of his return from a campaign in India. The two lateral sanctuaries flanking the main iwan each feature an elegant melon-shaped, longitudinally ribbed cupola whose outer shell is adorned with polychrome glazed ceramic tiles. Stalactite cornices form the articulation between each dome and a high cylindrical drum ornamented with belts of thuluth inscriptions

LANGUAGE

Today, mutual intelligibility between the Persian vernacular spoken in Uzbekistan and those in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan is limited without training. Beyond obvious differences in core lexicon and phonology which would otherwise constitute surmountable dialectical variation, easy intelligibility is hindered by pervasive Uzbekisms that are otherwise alien to Persian grammatical canons. These influences include a greater tendency towards agglutination, such as in the form of prepositional suffixes, as well as a complex system of conjunct auxiliary verbs which furnish participles with metaphorical ‘modes of action’, among others. Some of the salient features of the Samarqand and Bukhara dialects vis-à-vis Western Persian are outlined here.

*note: The future of the official orthography for the Uzbek language–that is, Cyrillic vs. Latin script–is currently the subject of heated debate. The Latin script (Lotini) will be used in this article. In contrast, the Standard Tajik language is written in a modified Cyrillic script, and official Tajik-language newspapers published in Uzbekistan also use this orthography.

GRAMMAR AND MORPHOLOGY

The Persian directional preposition به /be/ “to, towards” is a suffix in Samarkand Tajik (-ба /ba/), and its function is more versatile, occupying a variety of semantic fields corresponding to the diversified Uzbek use of -da, -ga. This constitutes a departure from both Standard Tajik and Western Persian vernaculars–wherein prepositional suffixes are absent–and a convergence with Uzbek Turkic agglutinative structure:

| Uzbek | Samarkand Tajik | Western Persian | English |

| Qozonda tuz tushdilar | Дегба намак рехтан Degba namak reḵtan | نمک توى ديگ ريختن Namak tūye dīg riḵtan | They poured salt into the pot |

| Bizlarga non beringlar | Моҳонба нон детон Mohonba non deton | به ما نان بديد Be mâ nân bedid | Give us bread (“to us”) |

| Bolalar uchun yangi maktab ochdilar | Бачаҳонба мактаби нав гушодан Bačahonba maktabi nav gušodan | مدرسه جديدى براى بچهها باز كردن Madreseye jadidi barâye baččehâ bâz kardan | They opened a new school for the children |

| Shunga | ҳаминба Haminba | به خاطر همين Be ḵâtere hamin | For this reason |

| Toshkentga kelganimda | Тошкентба омадамба Toškentba omadamba… | وقتى كه به تاشكند آمدم Vaghti ke be Tâškand âmadam… | When I came to Tashkent… |

| Onam bu mavzu haqida gapirib qoldi | Модарам ин мавзуба суҳбат карда монд Modaram in mavzuba suhbat karda mond | مادرم شروع كرد راجع به اين موضوع صحبت كردن Mâdaram shoru’ kard râje’ be in mowzu’ sohbat kardan | My mother suddenly began to talk about this subject |

| Tepada turgan | Таппаба истода Tappaba istoda | روى تپه ايستاده Rūye tappe istâde | Standing on top of the hill |

As such, the prepositional suffix -ба /-ba/ is very powerful indeed in that it is encountered in a remarkable number of semantic fields corresponding to Western Persian توى tūye “in, into”, به be “to”, براى barâye “for”, به خاطر be ḵâtere “for [a reason], وقتى كه vaghti ke “when”, راجع به râje’ be “about”, بر روى bar, rūye “on, atop.” In formal speech, the more specified prepositions are used. Finally in the ablative and locative constructions, /-ba/ may occur in fields in which it would be considered redundant in Western Persian: haminjaba “right here” (literally “in right here”), a feature which is shared with dialects in northern Afghanistan (da inja).

Note: The dialect of Bukhara uses a unique ablative case suffix -бан /-ban/ “from”: Наманганбан Фаргонаба рафтем Namanganban Farġonaba raftēm “We went from Namangan to Ferghana.”

Northern Tajik has developed numerous prepositional suffixes such as кати -kati or truncated ки –ki “with” (also found in Afghan dialects, as a prepositional prefix قت qat-e), барин -barīn “like”, and баъд /-ba’d/, пас /-pas/, апушта a’ pušta “after”. For example, dadem-kati Khuqandba raftēm (Uzbek: otam bilan Qo’qonga ketdik) “I went to Kokand together with my father”; man ham kalon šavam bobom-barīn tariḵčī šudanī (Uzbek: men ham katta bo’lganimda, otam kabi tarikhchi bo’laylik) “When I grow up, I want to become a historian like my father”; in suruda navistan-ba’d (Uzbek: bu qo’shiqni yozishidan keyin) “after writing this song…”, whereas enclitics are absent in Western Persian: ba’d az neveštan-e in âhang. These examples are represented in table form below:

| Uzbek | Samarkand Tajik | English |

| otam bilan Qo’qonga ketdik | дадем кати Хуқандба рафтем dadem-kati Khuqandba raftēm | I went to Kokand together with my father |

| men ham katta bo’lganimda, otam kabi tarikhchi bo’laylik | ман ҳам калон шавам бобом барин тарихчӣ шуданӣ man ham kalon šavam bobom-barīn tariḵčī šudanī | When I grow up, I want to become a historian like my father |

| bu qo’shiqni yozishidan keyin | ин суруда навистан баъд in suruda navistan-ba’d | After writing this song |

The superlative construction uses an Uzbek loan eng in place of Standard Persian ترين –tarīn: eng baland “the tallest” (Western Persian: بلندترين boland-tarīn).

In addition, a number of native Persian constructions have evolved to mirror Uzbek. These include:

1) –anī construction, parallel to Uzbek –moqchi signifying will or intent (discussed below), and all of its derived uses with + bo’lmoq“to be, become”

2) –onda construction, parallel to Uzbek -yotgan signifying a continuous action

| Uzbek | Samarkand Tajik | Western Persian | English |

| Agar dasturda qatnashmoqchi bo’lsangiz… | Агар барномаба ширкат карданӣ бошетон… Agar barnomaba širkat kardanī bošeton… | اگر بخواهيد در برنامه شركت كنيد… Agar beḵwâhid dar barnâme šerkat konid… | “If you would like to participate in the program…” |

| Olov uyni yondirmoqchi bo’lardi, lekigin ko’klamgi yomg’ir uni bartaraf etgan | Алов хоная сухтанӣ мушуд, аммо борони баҳорӣ вая хомуш кард Alov xonaya suxtanī mušud, ammo boroni bahori vaya xomuš kard | آتش ميخواست خانه را بسوزد، ولى باران بهارى آتش را خاموش كرد Ataš miḵwâst ḵâna râ besuzad, vali bârâne bahâri âtaš râ ḵâmuš kard | “The fire was about to burn the house, but the spring rains extinguished it” |

Communal commands follow the Uzbek pattern using the past tense of the 1st person pl.: рафтем raftēm “let’s go” (literally: “we went”, often preceded by набошад nabošad; compare Uzbek ketdik bo’lmasa) as opposed to Western Persian which uses the subjunctive prefix /be-/: برويم beravīm. The second person plural enclitic is -етон -eton (Western Persian: يد- –īd):

|

Northern Tajik |

Western Persian |

English |

|

дастатонба гиретон |

تو دستتان بگيريد |

“Hold [it] in your hands” |

|

гуетон |

بگويد |

“Say!” (pl., command) |

Masjid-i Bolo Hauz (c. 1712 A.D.) Bukhara, Uzbekistan. The most striking feature of this mosque are the twenty slender wooden columns, each comprised of two trunks bound together by metal rings, and crowned with painted stalactite capitals. The mosque takes inspiration from Safavid pavilion forms, such as the Chehel Sotun Palace in Isfahan, Persia.

The Uzbek emphatic/intensifying modal particle -ku or a Tajik equivalent -da is used when there is doubt whether the interlocutor is aware/sure about the information, or in order to intensify the sentiment: xама ҷоиба ҳамту-ку! hama joyba hamtu-ku! “It’s like this everywhere!” (cf. Uzbek hamma joyda shunday-ku!); мушудаст-ку mušudast-da! “Bravo!” (calqued from Uzbek bo’lardi-ku; note alternative expressions are also used: Standard Tajik офарин ofarin and Russian молодец/молодцы molodets’/molodts’y.)

Another peculiarity of Northern Tajik is the present continuous tense of the verb. In contrast to Western Persian, the formal register of the language employs a construction consisting of the past participle followed by a conjugated form of the desemanticized verb истодан istodan (originally meaning “to stand”) in lieu of Western Persian داشتن dâštan (“to have”). This feature is shared with Standard Tajik. However, the informal register of the language employs a contracted reflex of this past participle + istodan form, resembling the Uzbek focal present form –yap-, whereby -[i]s- in Samarkand and -ašt- in Bukhara:

| Samarqand Tajik (colloquial) | Standard Tajik | Western Persian (colloquial) | English |

| mehnat kaisem | меҳнат карда истодам mehnat karda istodam | دارم زحمت مى كشم dâram zahmat mikešam | I am working hard [currently] |

| davom daisem | давом дода истодам davom doda istodam | دارم ادامه ميدم dâram edâme midam | I am continuing |

| omaisas | омада истода omada istoda | داره مياد dâre miyâd | S/he/it is coming |

| varaq zaisem | варақ зада истодам varaq zada istodam | دارم ورق ميزنم dâram varaġ mizanam | I am turning the page |

| kalon šusen | калон шуда истодан kalon šuda istodan | دارن بزرگ ميشن dâran bozorg mišan | They are getting bigger |

| chi puxseton? | чӣ пухта истодаед? chi puḵta istodaed? | چي داريد ميپزيد؟ chi dârid mipazid? | What are you(pl.) cooking? |

An alternate use of desemanticized гаштан gaštan (originally meaning “to roam, wander”) for the auxiliary usually gives a perfect progressive sense: kor karda gašta-ast “he has been working.”

Characteristic of Northern Tajik spoken in Uzbekistan are conjunct (or serial) verbs, of which the progressive tenses (see above) are grammaticalized instances. There are some eighteen lexically established conjunct auxiliaries corresponding to models in Uzbek, which in regularly conjugated tenses furnish adverbial ‘modes of action’ for the non-finite participle—which is, semantically speaking, the main verb. Some are fairly literal in sense: kitob-mitob ḵarida mebarad “he buys (up) books and stationery (and takes them away with him),” to highly metaphorical: in adrasa pūšida bin “try on this resist-dyed tunic” (дидан/бин didan/bin- ‘to see,’ tentative mode; cf. Eng. “see if it fits”). Other typical conjunct auxiliaries are гирифтан giriftan ‘to take’ (self-benefactive): dars-i nav-ro navišta giriftem “we copied down the new lesson”; додан dodan “to give” (other-benefactive): nom-i ḵud-ro navišta mēdiham “I shall jot down my name (for you)”; партофтан partoftan “to throw (away)” (complete or thorough action): berunho-ya toza karda rūfta parto! “sweep all the outside nice and clean!” This last illustrates a double conjunct construction, the auxiliary governing both of the non-finite forms of руфтан rūftan “to sweep” and тоза кардан toza kardan “to clean” (a typical Persian-type composite verb).

Colloquially, the copula is omitted: вай номашон Дилбар vay nomashon Dilbar “Her name [is] Dilbar.” Non-finite verb forms are used much like in Uzbek: шумо озмойш карданӣми? šumo ozmoiš kardani-mi? “Are you going to give it a try?”; ин маҳаллаба моҳон чил у панҷ сол яша кадагӣ; In mahallaba mohon chil u panj sol yaša kadagi “We have lived in this neighborhood for forty-five years”; ман дар бораи чашмаҳо китоб навистагӣ man dar borayi čašmaho kitob navistagi “I have written a book about fresh water springs”.

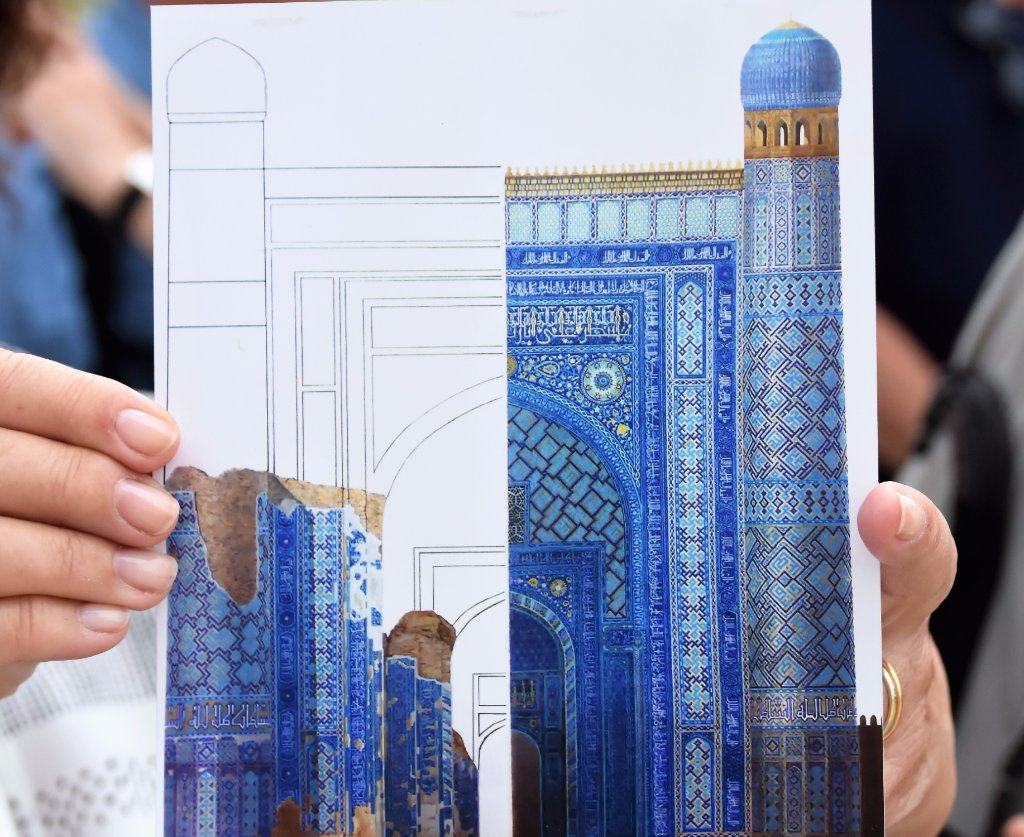

Remains of the entrance portal to Timur’s royal palace “Oq Saroy” at Shahrisabz, Uzbekistan. The Spanish ambassador, Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, who passed through Shahrisabz in 1404, was astounded by the structure’s enormous scale and elaborate ornamentation using dark blue- and turquoise-colored glazed ceramic tiles. Brick mosaic work, forming large geometrical and epigraphic designs on a background of polished building brick, affords the portal a special softness of color and an air of grand mystery. Calculation of the proportions of the surviving elements of the site makes it fairly certain that the height of the main portal reached 70 m (230 ft). It was topped by arched pinnacles (ko’ngra), while corner towers on a multifaceted pedestal were at least 80 m high. Today, only the lower segment of the pillars and part of the arch remain.

Occasionally the contracted enclitic form of the 1st person copula is substituted wholesale from Uzbek. This occurs particularly at the end of the -anī construction, which is based on Uzbek –moqchi signifying will or intent, whereby -man instead of Persian -[hast]am: Man bukhorocha usluba yod giftaniman “I intend to learn the Bukharian style [of embroidery]”; man unjaba raftaniman “I want to/will go there” (Uzbek: men uyerga ketmoqchiman).

*Note: in the first example above, the Uzbek construction bukhorocha uslub is used instead of Persian uslūbi bukhoroi, which is considered canonical.

Representing another radical departure from Persian syntax and morphology, colloquial Northern Tajik displays synthetic relative constructions in lieu of post-nominal subordinate or relative clauses (e.g. constructs using Persian ke که “that”; although, these do exist in the formal register and Uzbek through Tajik influence). It instead mimics Turkic nominalized clauses:

| Uzbek | Samarkand Tajik | Western Persian | English |

| U aslida menga do’st emasligini tushundim | Vay aslašba manba do’st nabudageša famidam | Fahmidam ke u dar haqiqat dust-e man nist | I realized that he/she is not really my friend |

| Sizlarga ham kattakon raxmat o’yinimizda qatnashganingiz uchun | Šumohonbayam raxmati kalon bozemonba qati šudagetonba | Az shomâ ham kheyli mamnun ke dar bâzi–ye mâ sherkat kardid | Thank you very much too for partaking in our game |

| Chunki u hayotda baxt nimaligini bilmagan odam, shuning uchun sevgiga ishonmaydi | Chunki u xayotba baxt chi budageša namedonistagi odam, azbaroi hamin naġz didanba bovar namukunad | Chon u âdami ast ke tâ hâlâ nadâneste khoshbakhti dar zendegi chist, be hamin dalil be eshgh bâvar nadârad | Because he is a person who has not known what happiness is in life, that’s why he doesn’t believe in love |

Northern Tajik makes extensive use of the verbs баромадан baromadan (coll. buromdan) “to come out” and баровардан barovardan (coll. burovardan) “to bring out”, which are parallel to the versatile Uzbek verbs chiqmoq and chiqarmoq, respectively. For example: Зўр буромадаст zōr buromdast “It came out great/wonderfully” (cf. Uzbek zo’r chiqibdi). Notably, these verbs are conjugated with the affix bar- treated as part of the verb stem. Баровардан barovardan is sometimes used in lieu of the Western Persian verbs بردن، آوردن bordan, âvardan “to take”, “to bring.” For example: писар хиёнат кунад агар, духтар кечири мукунад лекин ҳеч вақт а есаш намубурорад pisar ḵiyonat kunad agar, duḵtar kečiri mukunad lekin heč vaġt a’ esaš namuburorad “If a guy cheats, the girl will forgive him but she will never forget it” (cf. Western Persian: از یادش نمى برد az yâdaš nemibarad; cf. Uzbek: yigit xiyonat qilsa agar, qiz kechiradi lekin hech qachon esidan chiqarmaydi.)

The Turkic interrogative particle -ми –mi is used in final position, or as an enclitic on the component questioned. In Western Persian, a construction using آيا âyâ is optionally used:

| Uzbek | Bukhara/Samarkand Tajik | Western Persian | English |

| Siz Buxoro shahrini yaxshi ko’rasizmi? | Шумо шаҳри Бухороя нағз мебинедми? Šumo šahri Buḵoroya naġz mebined-mi? | آيا شما شهر بخارا را دوست داريد؟ Âyâ šomâ šahre boḵârâ râ dust dârid? | Do you like the city of Bukhara? |

| Otasi bilan tanishdingmi? | Падараш кати шинос шудими? Padaraš-kati šinos šudi-mi? | با پدرش آشنا شدى؟ Bâ pedaraš âšenâ šodi? | Did you meet his father? |

Occasionally, a construction signifying ownership is calqued from the Uzbek nominal predicate bor, whereby: pronominal enclitic + ҳact hast (“to exist”) instead of the Persian verb داشتن dâštan (“to have”): Tuya eng naġz mididagi aktriset hast-mi? Ha, hast (Uzbek: Senda eng yaxshi ko’radigan aktrising bormi? Ha, bor.) “Do you have a favorite actress? Yes, I do.” The corresponding optional construction for “to not have” is based on Uzbek yo’q, whereby: pronominal enclitic + нест nēst (“to not exist”) instead of the Persian verb نداشتن nadâštan (“to not have”): хабаромо нест ḵabaromo nēst (Uzbek: xabarimiz yo’q) “I don’t have knowledge [of that].”

The Western Persian deontic modality using بايد bâyad is not encountered colloquially, but is used infrequently in the literary register. Instead, the auxiliary даркор darkor is placed following the clause. This construction mirrors the Uzbek form using kerak:

| Uzbek | Samarqand Tajik | Western Persian | English |

| Kelajakda shundan ham ko’proq harakat qilishimiz kerak | Ояндаба аз ин ҳам зиёда ҳаракат кардагомон даркор Oyandaba az in ham ziyoda harakat kadagomon darkor | در آينده بايد از اين هم بيشتر تلاش كنيم Dar âyande bâyad az in ham bištar talâš konim | In the future, we have to try even harder than this |

In contrast to Western Persian, the reporting of speech centers on гуфта gufta (occasionally гуйон gūyon), a non-finite form of гуфтан guftan “to say” with the speech string preceding, forming a sort of idealized quotation to explain the cause or purpose of the action in the main clause. It also the proceeds the statement of an opinion. This form has evolved on the analogy of a typically Turkic construction, using deb/degan “saying” in Uzbek:

| Uzbek | Bukhara/Samarkand Tajik | English |

| Onamiz doimo yaxshi xizmat qilinglar, hech qachon boshqa odamlarga yomon gaplar aytmanglar deb bizlarga o’rgatib kelgan | Očamon hameša naġz xizmat kuneton, hečvaght hečkasba gapi ganda nazaneton gufta mohonba yod doda omadagi | Our mother has always taught us to work hard, and to never speak disrespectfully to others. |

| Agar ota-onam topgan bol’salar demak yaxshi bola deb o’ylayman | Agar xonangom yoftagi boshan demak naġz bachcha gufta o’yla mukunam | If my parents found him, then I think he is a good guy |

Madrasa-i Sherdor (c. 1636 A.D.) in Registan square, Samarkand, Uzbekistan. “Sherdor” translates to “baring lions” in Persian.

LEXICON

Northern Tajik features numerous archaisms, as well as neologisms and loanwords from Uzbek and Russian. In some instances, alternative native forms vis-à-vis Western Persian have developed or been differentially favored over time: such as the suffix –kati or simply -ki for Western Persian bâ “with” (also found in Afghan dialects as a preposition qat-e); ganda for Western Persian bad “bad”; kalon for bozorg “big”; xursand for xošhâl “happy”; pagah for fardâ “tomorrow”; mayda, xurd for kučak “small, little, young”; šifokor for pezešk “doctor”; san’atkor for honarmand “artist; singer”; tayyor for âmâde, hâzer “ready”; anakun, akun for al’ân, aknun “now”; iflos for kasīf “dirty”; pēš, soni for qabl, ba’d “before, after”; –barin for mesle “like”; o’īd ba for râje’ be “about, concerning”; pazandagi for âšpazi “cooking”; harakat kardan for sayy’ kardan, talâš kardan “to try”; sar šudan for šoru’ šodan “to start”; daromadan for vâred šodan “to enter”; bevaqt for dir “late”; monda, halok for xaste “tired”; šištan for nešastan “to sit”; partoftan for raftan “to leave”; xezedan for pâ šodan “to rise, get up”; mondan for gozâštan “to place, to lie (object onto a surface)”; fursondan for ferestâdan “to send”; foridan, whence foram “pleasing”, for ḵoš âmadan “to please”; allondan for farib dâdan “to cheat, delude”; koftan/kobedan for jostojū kardan “to look for, search”; mazmun for ma’ni “meaning”; jindi for divâne “crazy”; mehnat for zahmat “exertion; duty to another according to prevalent Iranian social ideals”; yoftan for peydâ kardan “to find”; dastgiri for komak “help”; chuva for cherâ “why”; yakjoya for bâ hamdigar “together”; sonitar for ba’dan “then, after”; apušti for donbâl-e “follow, pursuit”; azbaroi or postposition baroš for barâye, vâse “for; for the purpose of”; darkor for lâzem, bâyad “need”; minnatdor for mamnūn “thankful”; xunuk for zešt “ugly”; naġz (Samarkand) and sara (Bukhara) for Western Persian ḵūb “good“; nēk for qašang “beautiful, nice”; ḵušrő and dősrő for zibâ “beautiful”, among others.

There are a few verbs which function differently from Western Persian, such as буровардан burovardan for درست كردن dorost kardan “to make, to produce”. In this case, the adjunct bar- is treated as part of the radical: hence, present tense mebarorand instead of bar meyorand “they produce.” Additionally, the verb омадан omadan “to come” in the present tense uses the stem biyo- instead of â-: mebiyod instead of miâyad.

Common loanwords from Uzbek include qiziq for jâleb “interesting”; qiyin for saxt, moškel “difficult”; ovqat for ġazâ “food”; omad for xošbaxti ‘”good fortune, luck”; yigit for mard “boy, young man”; yordam for komak “help”; juda for xeyli “very”; yaša kardan for zendegi kardan “to live”; őyla kardan for fekr kardan “to think”; qišloq for deh “village”; turmuš, tōy for ezdevâj, arusi “wedding”; kelin for arus “bride; yošagi for bačegi “childhood”; qiziqi kardan for alâghe dâštan “to take interest in”; es for yâd “memory”; butun for kâmelan “completely”; rivojlani for pišraft “development, progress”. As discussed above, the majority of Persian speakers in Uzbekistan are bilingual in both Persian and Uzbek.

In some cases, phraseology has been calqued from Uzbek, such as Tajik naġz didan for Uzbek yaxshi ko’rmoq “to like; love” (but literally “to see as good”).

Russian loans dating to the Soviet period are more numerous than those found in Standard Tajik, which has replaced most Soviet-era loans with native forms. The lexemes are usually technical terminology pertaining to science, transport, technology and government administration: вокзал vokzal “train station”, аеропорт aeroport “airport”, операция operatsiya “operation”, композитор kompozitor “musical composer”, реконструкция rekonstruktsiya “reconstruction”, ассоциация assotsiatsiya “association”, рестоврация restovratsiya “restoration”. Some Russian loanwords have been assimilated to the native phonology, such as корейс Koreiis “A member of the Soviet Korean community in Uzbekistan” (Russian has корейц Koreiits’).

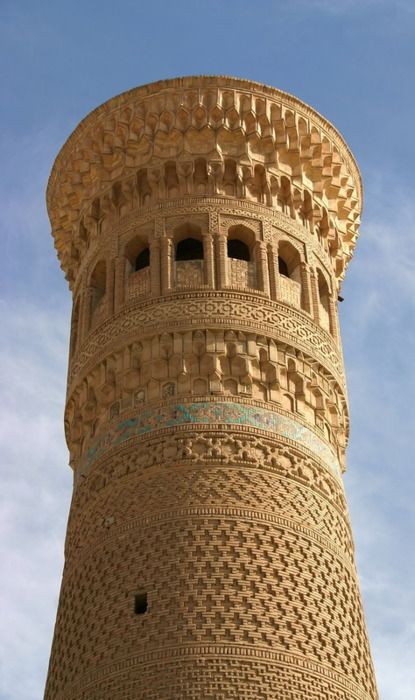

The Kalon Minaret (Минораи Калон “Great minaret”), designed by “Bako” according to the frieze, was commissioned by the Qarakhanid ruler Mohammad Arslan Khan in 1127 A.D. and stands at 48 m (157 ft). Proving the versatility of sun-baked brick, each band is composed of either circular, square or rectangular bricks arranged in differing patterns to give an extraordinary texture. The body of the minaret is topped by a rotunda with 16 arched fenestrations forming a gallery, which is in turn is crowned by a magnificent cornice adorned with muqarnas (stalactites) and a pointed conical stump.

The pronouns are similar to those in Southern Tajik, including вай vay and вайхо vayho for the 3rd person singular and plural. This has been elaborated colloquially to mean “he”, “she”, “it”, and “that”. In Western Persian, its equivalent وى vey is only encountered in the meaning of “he, she” and its use is restricted to the literary register, particularly in media and news broadcast, while it is never encountered colloquially.

The Persian 1st person pl. pronoun ما mâ “we” is used with a plural suffix forming an ‘explicit plural’, which may also refer deprecatingly or deferentially to a singular person: моҳон mo-hon “I/We” (often heard as мон mon); while mo without a plural suffix is heard in compounds: mo-yam gɵsh metemda “we are listening [right now] too“, otherwise its use is restricted to the literary register. Similarly, šumo ‘you’ (sg. or pl.) becomes šumo-yon, šumo-ho ‘you (pl.)’.

The deferential pronoun ešon for 3rd person plural (“he, she,” lit. “they;” cf. Pers. ايشان išān) evolved into an honorific title for religious notables, and has been replaced in Northern Tajik by ин кас in kas or ун кас un kas (lit. “this person”, “that person”).

Tajik-Uzbek artist Munira Mukhammedova (right) at Navruz (Persian New Year) celebration in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Tajik Persian: Чи кардам, ин ки ту дил канди аз мано; Зи роҳи ваъдаи худ рафта берун (či kardam inki tu dil kandi az mano, zi rohi va’dai ḵud rafta berun)

English: What did I do, that you have torn your heart away from me? That you have transgressed from the path of your own promises?

PHONOLOGY

Bukharan Tajik and the dialect of Samarkand belong to the Northern dialects, which share basically the same phoneme inventory.

There are differences in pronunciation between Northern Tajik spoken in Uzbekistan and the dialects of Tajikistan. Colloquially, certain words are transformed rather radically, following a pattern whereby medial consonant clusters are truncated or omitted entirely, such as giftan or gitan for гирифтан giriftan “to take; to get”; kadan for кардан kardan “to do” (the latter also found in Afghan dialects).

Additionally, Northern Tajik–as opposed to Standard Tajik–has the phoneme /ő/, but the close-mid central vowel is pronounced /ū/ in Standard Tajik:

| Samarkand Tajik | Standard Tajik | English |

| mőgőt, mőgőftan | mēga, mēguftan | S/he says, they were saying |

| mukunat | mēkuna | S/he does |

| namőšőd | namēšud | It couldn’t happen |

| dősti | dūsti | Friendship |

| gőšt | gūšt | Meat |

| őzbeg | ūzbak | Uzbek |

There are slight variations in pronunciation between the Tajik varieties in Bukhara and Samarkand cities:

| Bukharan Tajik | Samarkand Tajik | English |

| mēgőm | mőgőm | I say |

| dilom dard mēkunat | dilam dard mukunat | It pains me (lit. “my heart hurts”) |

| Da bozor namērőm | Bozorba namőrőm | I won’t go to the bazaar |

| Uno kadašten | Vayon kaisen | They are doing it |

Tajik direct object marker -ra becomes -a after consonants and -ya following vowels

| Northern Tajik | Standard Tajik | English |

| man tuya naġz mebinam | man turo dūst medoram | I love you |

Sources:

Bhatia, Tej K. “Societal Bilingualism/Multilingualism and Its Effects.” The Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism, 2012, pp. 439–442., doi:10.1002/9781118332382.part3.

Encyclopaedia Iranica

Finke, Peter. Variations on Uzbek Identity: Strategic Choices, Cognitive Schemas and Political Constraints in Identification Processes. 1st ed., Berghahn Books, 2014. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qck24.

Foltz, Richard. “The Tajiks of Uzbekistan.” Central Asian Survey, vol. 15, no. 2, 1996, pp. 213–216., doi:10.1080/02634939608400946.

Ido, Shinji. “Bukharan Tajik.” Journal of the International Phonetic Association, vol. 44, no. 1, 2014, pp. 87–102., doi:10.1017/s002510031300011x.