Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. Part of this narrative stems from the author’s visits to Armenia and the Tehrani Armenian community between 2014-5. The goal of this article is to familiarize the reader with the Christian Armenian community of the Islamic Republic of Iran, with a focus on its culture and language in a historical and modern setting.

Christmas festivities in an Armenian kindergarten, Isfahan, Iran (1989) | Ձմեռ Պապ, Մանկապարտեզի հանդես, Նոր Ջուղա (1989)

INTRODUCTION

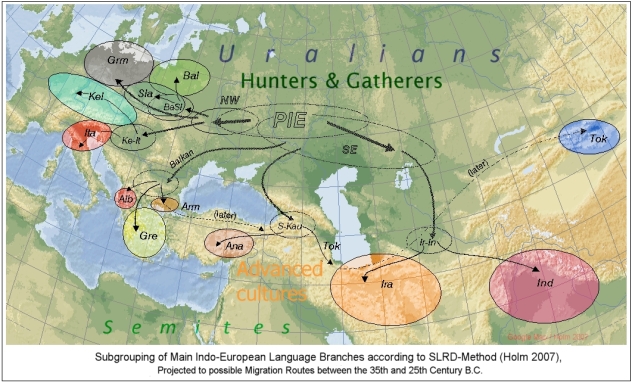

Armenian (self-designated Հայերեն Hayeren) is an eccentric, satem member of Indo-European and occupies its own clade within that family. Of note, it does not belong to Indo-Iranian or Balto-Slavic. Without any immediate sisters, Armenian is joined by Greek and Albanian as an extant isolate within the Indo-European family.

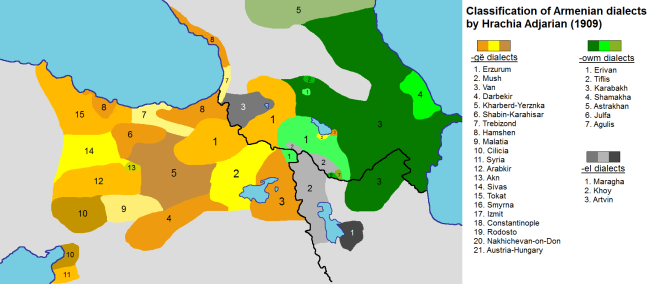

Modern Armenian constitutes a pluricentric language with two standardized forms. The main typological split is between Eastern Armenian (Արևելահայերեն Arevelahayeren)—derived from the language of the 18th century Russified Armenian intelligentsia (Հայ մտավորականություն Hay mtavorakanut’yun) centered in Tiflis—and Western Armenian (Արևմտահայերեն Arevmtahayeren), the contemporaneous language of the Ottoman Armenian elite centered in Constantinople. These two standardized forms represent poles in a spectrum comprised of various intergrading dialects that once spanned a putative homeland from Sivas to Baku, disregarding the historical Armenian diaspora (Սփյուռք Sp’yurrk’) which at its height reached as far as London and Java. Until the 19th century, Armenian constituted a diglossia whereby literature was composed in the archaic, otherwise unintelligible Classical Armenian language (Գրաբար Grabar)—now limited to liturgy—while the spoken vernaculars (Աշխարհաբար Ashkharhabar) belonged to the Eastern and Western varieties detailed above. The two spoken varieties are only moderately mutually intelligible without training.

Distribution of Western (orange hue) and Eastern (green hue) Armenian varieties, prior to the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Today Eastern Armenian is the official language of post-Soviet Armenia (green, #1); Western Armenian holds no official status and is classified as a “definitely endangered language.”

The Armenian varieties encountered in Iran belong to the Eastern subgroup, as do the dialects of Georgia, Nagorno-Karabagh, and Russia. However Parskahayeren is unique within the Eastern group in that it rejected the reformed Abeghian orthographical conventions of Soviet Armenia in 1922, and is thus confederate with its distant Western Armenian cousin in retention of the ancient Mashtotsian orthography originally used to write Classical Armenian (Grabar). Following the Armenian Genocide of 1915, the Western subgroup is now centered in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, and abroad, but was once native to the highlands dotting modern-day Turkey.

| English | Mashtotsian Orthography (Iran) | Abeghian Orthography (Armenia, Russia, Georgia, since 1922) | Eastern Armenian Pronunciation (Iran & former U.S.S.R.) |

| “Resurrection” | յարութիւն yarowt’iwn |

հարություն harout’youn |

harut’yun |

| “Hope” | յոյս yoys |

հույս houys |

huys |

| “Europe” | Եւրոպայ ‘Ewropay |

Եվրոպա ‘Evropa |

Yevropa |

| “In the morning” | առաւօտեան arrawōtean |

առավոտյան arravotyan |

arravotyan |

In 1749-1769 the two volumes of the Barrgirk‘ Haykazian Lezvi, a dictionary of the Armenian language, were published by Mkhit’ar Sebastats’i and his Armenian Catholic congregation in Venice, Italy—making Armenian the sixth world language to have such a complete dictionary (after Latin, Greek, French, Italian, and Spanish; the first English dictionary appeared in 1755.)

Armenians refer to themselves as Հայ Hay, and to Iran as Պարսկաստան Parskastan “Persia”, from Պարսիկ Parsik “a Persian”, and hence the root of the terms Պարսկական Parskakan “Persian (non-human adjective)”, Պարսկահայություն Parskahayut’yun “Iranian Armenian community”, Պարսկերեն Parskeren “Persian language”, and Պարսկահայերեն Parskahayeren “Language of the Iranian Armenians”.

Monastery of St. Stephen the Protomartyr (Սուրբ Ստեփանոս վանք, Մաղարդավանք Surb Step’anos vank’, Maghardavank’; كليساى استفانوس مقدس Kelisā-ye Estefānūs-e Moghaddas) East Azerbaijan province, Iran (1330 A.D.)

ARMENIAN HISTORY IN IRAN

The link between Armenia and Persia is about as old as the foundation of the Persian Empire in the 6th century B.C., but the modern Armenian-Iranian nucleus has its genesis in the late medieval period. It should be noted that no pre-genocide Armenian colony (Գաղութ Gaghut’) has enjoyed the extent of affluence, relevance, and repute in its host society as the Armenian diaspora of Persia. Iran has served as a stage for momentous developments in Armenian matters, in certain contexts even eclipsing the territories considered to be at the core of Historical Armenia (Մեծ Հայք Medz Hayk’) in power and consequence.

Khoja Petros Velijaniants’ (left) financed the St. Bethlehem Church (Սուրբ Բետղեմ Surb Betghem; كليساى بيت اللحم Kelisā-ye Bayt ol-Lahm) in Isfahan, Iran in 1628. His family opposed the rule of the Shafraz family in New Julfa, but they lost and left for Surat, India in 1638.

In a strategic move against the Ottomans that was meant to evacuate Nakhchivan, in 1604-5 Shah ʿAbbās I transplanted over 60,000 Armenian families (Բռնագաղթ Brrnagaght’), many of whom perished during a difficult winter in Tabriz, into the inner regions of Iran. But the Shah had a unique vision for a cohort of exceptionally skilled businessmen from the prosperous Armenian town of Julfa (Ջուղա Jugha; جلفا Jolfā) on the river Araks. Indeed among his most rewarding schemes in statecraft was the establishment of a world-class commercial district headed by a semi-autonomous Armenian merchant oligarchy of Julfan extraction in his new capital city, Isfahan, wherefrom Iranian silk was traded for European silver. In this exclusive, custom-built trading colony named New Julfa, the Armenians lived in symbiosis with the Safavid state insofar as they were sanctioned by royal decree (فرمان farmān) to preserve their distinct cultural, linguistic and religious identity (Հայկականություն Haykakanut’yun “Armenianness”), while melding harmoniously with the sovereign Persislamic socio-political infrastructure.

Under the patronage of Shah ʿAbbās I and his successors, who appreciated the Armenians’ talents and expertise, New Julfa soon transformed into a thriving center of craftsmanship and international trade replete with 24 churches. Contemporary French traveler Jean Chardin wrote that, in 1673– just two generations after the Julfan Armenians’ exodus from the Caucasus to Iran– Agha Piri, the head of the Armenian Community of Isfahan and one of its richest merchants, owned a fortune greater than 2,000,000 livres tournois (the equivalent of 1,500 kg of gold). Contrast with the textile merchants Beauvais and Amiens (the wealthiest merchants in France in the same period), the wealth of these two inventoried at their deaths amounted to 60,000 and 163,000 livres tournois respectively—a figure then considered astronomical. Yet these two figures combined amounted to barely a tenth of Agha Piri’s fortune.

For more on the history of New Julfan Armenians by the same author, click here (Part I) and here (Part II)

(Top) Interior of Vank Cathedral (Սուրբ Ամենափրկիչ վանք Surb Amenap’rkich’ Vank’; کلیسای وانک Kelisā-ye Vānk) completed 1664 A.D., New Julfa, Isfahan, Iran; (Bottom) New Julfa Armenian district, clocktower and museum (17th century), Isfahan, Iran.

Throughout the Safavid and Qajar periods, Armenian-Iranians served as brokers on behalf of Persia in both commercial and political contexts due to their common faith with Christian Europe and their familiarity with the languages and traditions of both East and West. The provost of New Julfa (Persian: كلانتر Kalāntar “Provost”; Armenian: Հայոց Թագավոր Hayots’ T’ak’avor, literally “King of the Armenians”) was chosen to hold official receptions for foreign embassies to Isfahan on the Allahverdi Khan bridge (later renamed Si-o-Se Pol), and the Armenians acted as a welcoming committee often introducing foreign visitors to the Safavid court. Hovhannes Vardapet, a native of New Julfa, introduced the first printing press into Persia from Italy (հրատարակչություն Hratarakch’ut’yun; چاپخانه Chāpkhāne), and the first book printed in Iran was the Armenian Saghmos (Սաղմոս “Psalms”) in 1638. In 1715, the last Safavid monarch Sultān Husayn sent an embassy consisting almost exclusively of Armenians to King Louis XIV’s court at Versailles, which resulted in the establishment of a permanent Persian consulate at the port of Marseille staffed by the Armenian “Hagopdjan de Deritchan.” Armenians continued to participate in national transformations through the Qajar period, and in 1850, Naser al-Din Shah’s chancellor Amir Kabir dispatched an Armenian, Mirza Davud, to Austria and Prussia in order to select six instructors in different fields for the modern polytechnic school that the chancellor was constructing, the Dār ul-Funūn (دار الفنون “House of the Arts”).

Bishop Papken Tcharian, prelate of Isfahan (Սպահանի Հայոց Թեմի Առաջնորդ Spahani Hayots’ T’emi Arrajnord), leads ceremony in Surb Amenap’rkich Cathedral, New Julfa, Isfahan, Iran.

The Armenian contribution to the overall configuration of the 20th-century Iranian society, both culturally and economically, is significant. Armenians were pioneers in photography, theater, and the film industry. The first movie theater to open in Iran (Tabriz, 1916) belonged to Alex Sahinyan, an Armenian who used the hall in the French mission of Tabriz as “Cinéma Soleil,” in which Russian and European films were shown to an enthusiastic audience. They were among the first to introduce Western music and dance to the Iranian public, and the Armenian contribution to modern Iranian music industry is varied and disproportionate to their small numbers. The popularity of modern fast-food establishments in Iran also owes much of its original success to the daring enterprise and perseverance of the Armenian businessmen who first introduced them in the Muslim society of Iran several decades ago. Armenian tailors, seamstresses, and beauty industry workers are of local renown, some of whom built national fashion brands from their small ateliers, such as the Hacoupian tailored suit brand (Հակոբեան; هاكوپيان) which can be found in Iran’s most exclusive shopping districts and hotels. Armenian athletes have represented Iran in international tournaments, particularly boxing, weightlifting, soccer, and volleyball.

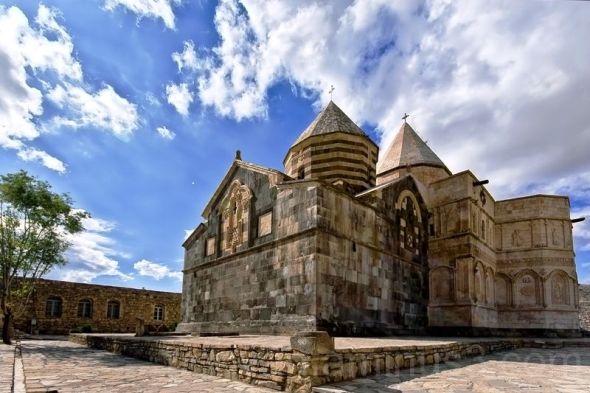

St. Thaddeus Monastery (Սուրբ Թադեոսի վանք Surb T’adevosi Vank’; قره كليسا Ghara Kelisā), Māku, Iran (1329 A.D.) In the past six centuries, more than 100 Armenian ecclesiastical structures have been commissioned in Iranian Azerbaijan, a few dozen of which are still standing today.

THE ARMENIAN PRESENCE IN MODERN-DAY IRAN

Today Tehran is the center of gravity for Iran’s ~150,000 Armenians, although this is a fairly recent transformation. The traditional centers of Azerbaijan and Isfahan (since the 17th century) have been overshadowed in recent years by the tremendous growth of the Armenian population in Tehran, where more than 60 percent of the entire community resides (meaning approximately 80,000-100,000 souls). Large-scale migration from Azerbaijan, particularly following the Turkish invasion of that province in World War I, and emigration from Armenia proper following the Russian revolution, rapidly turned Tehran into a haven. The Armenians are designated two seats in the Iranian Parliament (مجلس Majles, Խորհրդարան Khorhrdaran), whereas Jews, Zoroastrians, and Assyrian-Chaldeans are each designated only one. Three prelates with jurisdiction over the three district areas of Azerbaijan, Isfahan (including southern Iran and India), and Tehran (including central and eastern Iran) head the community. They were traditionally subject to the Catholicos of Echmiadzin in Soviet Armenia, but for political reasons aligned themselves with the Catholicos of Cilicia in Lebanon in the 1950’s.

St. Sarkis Cathedral (Սուրբ Սարգիս մայր տաճար Surb Sark’is mayr tachch’ar; كليساى سركيس مقدس Kelisā-ye Sarkis-e Moghaddas), Tehran, Iran.

The privileged status of Armenian is unusual in the context of the Islamic Republic, although Armenians have enjoyed unprecedented favor in a variety of contexts since their arrival to New Julfa in the 17th century. Paradoxically, Persian and Armenian are the only two languages with any official currency in today’s pluralistic Iran. Approximately 53% of Iran identifies Persian as its mother tongue, while only 0.1-0.2% speaks Armenian as a first language. The official language of education, media, and legislation is Persian, but Armenians are lawfully entitled to their own private kindergarten–12th grade schools wherein Armenian is a primary language of instruction alongside Persian (before the 20th century reforms under Reza Shah, Persian was taught as a foreign language alongside French and English; and Russian in Azerbaijan). There are approximately fifty Armenian private schools scattered throughout Iran today, from where Armenian students seeking higher education must pass a standardized national competency exam (كنكور Konkūr; Կոնկուրսի քննությունը Konkursi k’nnutyunё)—which includes Persian literature and Islamic theology—in order to integrate into national Islamic universities.

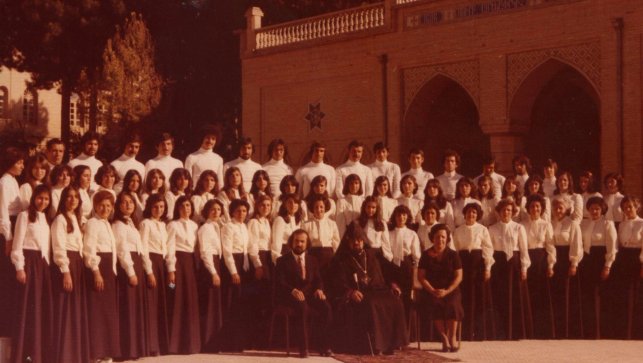

Surb Amenap’rkich Cathedral’s Choire led by Movses Panoian, New Julfa, Isfahan, Iran (1976) | Նոր Ջուղայի Սուրբ Ամենափրկիչ Վանք-ի Երգչախումբ; Ղեկավար : Մովսես Փանոսյան (1976)

Armenians manage and operate their own churches, schools, philanthropic organizations, sports clubs, night clubs, cultural associations and Armenian language publications including a daily newspaper based in Tehran, Alik’ Ōrat’ert’ (Ալիք Օրաթերթ “Wave Daily Newspaper”). In Tehran’s northern Vanak neighborhood, the Ararat Complex (Արարատ Միություն Ararat Miut’yun; باشگاه آرارات Bāshgāh-e Ārārāt) is a walled and gated, ~20-acre cultural and sports complex that only Armenians are permitted to enter (by government order), and wherein patrons are exempt from the Islamic guidelines governing inter-gender interactions including dress code (hejāb), and alcohol is legally consumed on the premises. As nationalist factions among Iran’s Azeris (16%), Kurds (10%), Arabs (2%), Turkmen (2%) and other ethnolinguistic minorities toil with the issues of language policy and cultural oppression, they seem wholeheartedly unaware of the status of Armenian. Perhaps this is due to their geographic location at the peripheries of Iran and subsequent disconnect from the happenings of Armenian-inhabited urban centers (except in the case of Azerbaijan). Or, perhaps, it is retained traditionalism in the long-standing belief that Christians can never be truly Iranian and thus constitute a quasi-foreign element in Iranian society.

Private Armenian night club, 2015 New Year’s celebration, Tehran, Iran (Photo by Afsheen Sharifzadeh) | 2015 Ամանորի դիմավորում, Թեհրան, Պարսկաստան

ON THE ISSUE OF IRANIAN BORROWINGS IN ARMENIAN (HISTORICAL LINGUISTICS)

Armenian shares two kinds of linkages with Persian. The first is ancestral, inasmuch as the two share a quite distant common ancestor in the form of the Proto-Indo-European language. Proto-Armenian probably split from the southwestern dialects of Proto-Indo-European around 3000 B.C., while Proto-Indo-Iranian split from the northeastern dialects around 2500-2300 B.C. For more on the Kurgan Hypothesis and PIE linguistics by the same author, click here

Persian and Armenian are genetically related languages. Pre-Armenian, Pre-Albanian, Pre-Phrygian, and Pre-Greek split off with PIE transhumance into the Balkans (and thence Anatolia, in the case of Armenian), but their origins are conflicting and their affinities with each other are problematic for a number of reasons that are outside the scope of this article (such as incongruities in Satemization and Centum superstrate; see Middle Dnieper multi-ethnic “vortex” culture for more reading).

The second link is cultural, as manifested in the form of several hundred loanwords borrowed from Old Iranian (Old Persian, Median, Avestan), Middle Iranian (Parthian, Middle Persian, Manichaean Parthian) into Classical Armenian, and to a far lesser extent, Modern Persian into Modern Eastern Armenian . The degree of Iranian borrowing throughout all registers of the language is so profuse that in the mid-19th century experts both in Armenian and in Iranian, foremost among whom were Paul de Lagarde and F. Müller, concluded that Armenian belongs to the Iranian group of Indo-European languages. That opinion prevailed until 1875, when H. Hübschmann pioneered a methodological principle whereby Iranian borrowings were separated in chronological layers from an Armenian core. That is to say, Old and Middle Iranian borrowings have effectively entered the ‘core’ of the Armenian language from the ‘periphery’, in that they have long since ceased to be perceived as loanwords and have become nativized phonologically. Analogously, the vast majority of loans are not readily recognizable to speakers of Modern Persian—in essence rendering this second linkage inoperative in the joint social memory of Iranians and Armenians.

Although Zoroastrianism was the predominant religion among Armenians for nearly 800 years before Christianization, conditions favorable to a fruitful cultural interchange between Armenians and Iranians existed almost exclusively during the rule of the Parthian (Iranian) Arsacids over Armenia (Արշակունիների արքայատոհմ Arshakunineri ark’ayatohm; سلسله اشكانيان Selsele-ye Ashkāniān). During that period the culture of the Parthian feudal aristocracy, being superior to that of the Armenians, exerted profound influence on the highlands. Accordingly, most of the linguistic borrowings came into Armenian from the Northwest Iranian language of the Parthians in a way comparable to the overwhelming French influence on English after the Norman conquest, although there are significant contributions from Southwest Iranian during the Sassanian period.

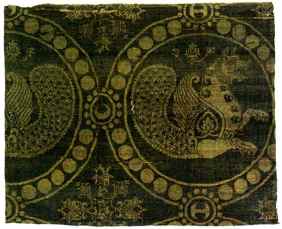

The Church of the Holy Cross at Aghtamar (Աղթամարի Սուրբ Խաչ եկեղեցի Aght’amari Surb Khach yekeghets’i), Lake Van, is based on ideas of 7th century Armenian architecture but the sculpture program is novel. The southwest façade (Top) features a sculpted scene of Jonah and the Whale in which the whale looks conspicuously like the Iranian mythological bird Simorgh (Middle Persian: senmurw → Armenian սիրամարգ siramarg “peacock”). The cross-legged figure on cushions draws from Islamic tradition. On the western façade (bottom right), Prince Gagik, commissioner of the Church, is depicted presenting a 3-dimensional model of the Aghtamar Church to Christ; Gagik is depicted taller than Christ and wearing a silk cloak with birds in randles—reminiscent of Sassanian silks (bottom left). As late as the 11th century, Aghtamar draws on Iranian signs of kingship and authority.

Nevertheless, the breadth of Iranian contributions to the Armenian stock has not been paid adequate attention in Armenian historiography. The reluctance of Armenians to acknowledge the contributions of the pre-Islamic but still inextricably Iranian world to their language, traditions, and material productions, and preference for the blanket term “pagan” (հեթանոսություն het’anosut’yun) in dealing with pre-Christian matters, likely has three causes. First, traditionalist Armenochristian intelligentsia remain sensitive to the longstanding history of massacre and subjugation, often but not always in the context of being a Christian minority in a Muslim society. The popularization of the term “pagan” in place of “Zoroastrian”, “Parthian”, “Persian”, “Iranian” or “Mithraist” accomplishes the goal of distancing the Republic of Armenia’s national heritage from the cultural property claimed by the neighboring Persislamic political apparatus. Second, the term “pagan” is reinforced by its currency in Christian doctrine and clerical texts; notwithstanding, the Iranianisms in the Armenian stock seem to be selectively trivialized, even vis-à-vis the more remote Urartian or Ancient Greek contributions. Finally, there exists a pervasive essentialist attitude among intellectuals and laypeople alike that any non-Christian agent in the Armenian national narrative cannot be truly “Armenian, and thus constitutes a foreign element in the otherwise continuous chronicle of a supposedly homogeneous nation.

According to Armenia’s folk conversion story, Gregory the Illuminator (top left; Գրիգոր Լուսավորիչ Grigor Lusavorich) was a Parthian (Iranian) Christian priest responsible for converting the Parthian (Iranian) king of Armenia, Tiridates III (top right; Տրդատ Արշակունի Trdat Arshakuni), to Christianity. Khor Virap monastery (bottom) in Ararat province, Armenia, marks the setting of these developments.

Despite a significant Iranian imprint, Armenian should not be viewed as a derivative language, but can be valued academically as a window into the Old and Middle Iranian linguistic landscape. Moreover the study of Iranian loans in Armenian is of vital importance for solving problems of Old, Middle, and New Iranian linguistics, in that they:

1. Help determine the exact phonetic shape of the (Middle) Iranian words, which in the Iranian texts is often obscured by the consonantal writing systems. The Armenian alphabet, however, is fully vocalized, though it does not show the original vowel quantity.

2. Enable us to establish the exact meaning of the Iranian words.

3. Shed light on the phonetic developments that took place in Iranian languages and thus aid in reconstructing linguistic stages not known or not sufficiently known from the Iranian evidence itself.

4. Provide evidence relating to Iranian, and especially Middle Iranian dialectological problems.

5. Finally, the Armenian language is also an important source for Iranian lexicology and lexicography as it contains many words, some of which survive right down to the present day, not attested in the Iranian languages themselves.

Dzordzor Chapel (Ծոր Ծորի Սուրբ Աստվածածնի մատուռ Dzor Dzori Surb Astvatsatsin maturr), the only standing remnant of a 9th century monastic complex, West Azerbaijan Province, Iran

Iranian borrowings span all registers of the language. It should be emphasized that these borrowings were not limited to lexical items but also involve derivational suffixes, phraseology, and all kinds of names, and that they are from the beginning of the Armenian literary tradition mixed with the inherited vocabulary of Proto-Armenian stock. A few are detailed in the table below (composed by Afsheen Sharifzadeh):

|

Modern Armenian |

Iranian root |

English |

| օրինակ ōrinak |

from Parthian *awδēnak. |

“Example” |

| շնորք, շնորհակալություն, շնորհավորել shnork’, shnorhakalut’yun, shnorhavorel |

from Middle Persian šnwhl (šnōhr, “gratitude, contentment”). Compare Manichaean Parthian ʿšnwhr (išnōhr, “grace; gratitude”), Avestan (xšnaoϑra-, “satisfaction”). |

“Gratitude, thanks, to congratulate” |

| կատակ katak |

from early Parthian *kātak; compare Middle Persian kʾtk’(*kāyag, “game; joke”) |

“Joke” |

| ժամանակ, ժամ zhamanak, zham |

from Parthian *žamānak (“time”), from jmʾn (žamān). Cognate with Middle Persian ẕmʾnk’ (zamānag) |

“Time; hour” |

| ճանապարհ, ճամփա, ճանապարհորդ ch’anaparh, ch’amp’a, ch’anaparhord |

from Iranian *čarana-parθ, composed of *čarana- (“to go”) and *parθ (“passage”). For the first part compare Avestan (kar-), (čara-), (čaraya-, “to move, to go”) |

“Path, road; traveller, wayfarer” |

| -յան -ian |

from Iranian *-yān, a postvocalic variant of the pluralization suffix *-ān, whence -ան (-an). |

(forming adjectives, common in Armenian surnames) |

| դժվար dzhvar |

from Iranian; Compare Middle Persian dwšʾwl (*dušwār, “difficult, disagreeable”), Persian دشوار (dušvār). |

“Hard, difficult” |

| պատասխան pataskhan |

from Iranian *pati-saxwan-iya, from Proto-Iranian *sanh-“to declare, explain” |

“Answer, response” |

| վտանգավար vtangavor |

from Middle Persian *vitang, from Old Persian *vitanka-(“hardship, peril, misfortune”), composed of the preverb *vi- (“down”) and the root *tanč- (“to twist (together), become narrow, dense, constrict”). |

“Dangerous, perilous” |

| հրեշտակ hreshtak |

A Middle Iranian borrowing; Compare Manichaean Parthian fryštg (frēštag, “apostle; angel”), Middle Persian plystk’ (frēstag, “apostle; angel”), Persian فرشته (ferešte, “angel”) |

“Angel” |

| ճաշ ch’ash |

from Middle Iranian *čāš. Compare Middle Persian (čāšt, “breakfast”), Persian چاشت (čāšt, “breakfast, early dinner”) |

“dinner, late meal, feast” |

| պատրաստ patrast |

from Middle Iranian *patrāst, from Old Iranian *patirāsta-, composed of the Proto-Iranian preverb *pati- (“against, towards”) + *rāsta- (“prepared”). Related to Persian پیراستن(perāstan, “to adorn”) and آراستن (ārāstan, “to adorn”) |

“Ready” |

| աշխարհ ashkharh |

With metathesis from Middle Median *axšahr, from Proto-Iranian *xšaθra- (“power, authority, dominance”). Compare Old Persian xšaça-, “kingdom, realm” |

“World, cosmos” |

| աշխատանք ashkhatank’ |

An Iranian borrowing, probably Middle Median because of the prothetic a-. Compare Middle Persian ʾxšʾd(“depressed, troubled”) |

“Work, labor” (originally fatigue, toil, trouble) |

| դպրոց dprots’ |

from Middle Persian (dipīr, “secretary, scribe”) + -ոց (-ocʿ) |

“school” |

| փառք p’arrk’ |

from Middle Iranian *farr + -ք (-kʿ). Compare Old Persian (farnā, “glory”), Persian فر (farr), Avestan (xvarənah-) |

“Glory, fame, renown, esteem” |

| –երեն –eren |

from Middle Iranian *āδēn |

Forms names of languages when appended to roots denoting names of nations or regions |

| նկար nkar |

from Iranian *nikar. Compare Manichaean Middle Persian ngʾr (nigār, “painting, picture”), Persian نگار (nigār). |

“Picture, image, painting” |

| ճշմարիտ, ճշմարտություն ch’shmarit, ch’shmartut’yun |

An Iranian borrowing. Compare Middle Persian cšm dyt’(čašmdīd, “visible, obvious”, literally “seen with (one’s own) eyes”). |

“True, real; truth” |

| Տիգրան Tigran |

from Old Persian *Tigrāna, derived through haplology from *tigrarāna (“fighting with arrows”), composed of (tigra, “arrow”) (compare Persian تیر (tir)) + *rāna-(“fighting”) |

A male given name |

| Վահագն, Վահան, Վահրամ Vahagn, Vahan, Vahram |

from Parthian *Varhraγn; ultimately from Avestan (Vərəθraγna, “Verethragna”, literally “smiting of resistance, breaking of defence; victory”). Related to Avestan (vərəθra, “shield, obstacle, defensive power”). All ultimately stemming from Proto-Indo-Iranian *Hurtra-(“cover”). |

Male given names |

| Գովել govel |

Borrowed from a Middle Iranian descendant of Proto-Iranian *gaub-; |

“To praise” |

| օգնություն, օգուտ, օգտակար ōgnutyun, ōgut, ōgtakar |

from Parthian *abigūt, *abi-gūna-. |

“Help, helpful, benefit” |

| -պես -pes |

from Middle Iranian *pēs. Ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *peyḱ-. |

“As, like” |

| -նման –nman |

from Iranian *nimān, composed of the prefix ni- and the root mān-. Compare, Persian مانا (mānā, “alike, equal, resembling”). |

“Like, resembling” |

| Գույն: սև, սպիտակ, կապույտ, կարմիր, մանուշակGuyn: sev, spitak, kapuyt, karmir, manushak |

from Middle Persian gwn’ (gōn, “colour; kind, sort”); From Parthian syʾw (syāw, “black”); From Middle Iranian *kapōt“grey-blue, pigeon”; From Middle Persian klmyr (*karmīr, “red, crimson”); from Middle Persian *manafšak, a by-form of wnpšk’ (wanafšag); |

“Color, black, white, blue, red, purple” |

The Temple of Garni (Գառնիի հեթանոսական տաճար Garrni het’anosakan tachch’ar), Kotayk Province, Armenia. Commissioned by the Parthian (Iranian) king of Armenia, Tiridates I, some scholars ascribe this Greco-Roman colonnaded structure to the Iranian deity Mithra (Միհր Mihr), who was a member of the Irano-Zoroastrian pantheon of pre-Christian Armenia (the Trinity: 1. Aramazd < from Ahura Mazda; 2. Mihr < from Mithra; 3. Anahit < from Anahita). (August 2015, Photo by Afsheen Sharifzadeh).

IRANIAN-ARMENIAN LANGUAGE

As in the case of Québécois French in Montreal, Armenian-Iranians within a single city seem to speak a variety of dialects that differ appreciably from each other in lexicon, pronunciation and sometimes morphology. This can be attributed to the diverse provenance of Armenians inhabiting Iran’s major urban centers—some tracing their roots to Iranian Azerbaijan (Ատրպատական Atrpatakan) particularly Tabriz (Դավրեժ Davrezh or Թավրիզ T’avriz), Urmia, Salmas, Khoy, and Maragha and its surroundings; Kermanshah and Hamedan; Ardebil and Rasht; New Julfa (Նոր Ջուղա Nor Jugha) in Isfahan (Սպահան Spahan) and Arak; Shiraz; Abadan and Ahwaz; or to a number of Armenian villages scattered throughout central Iran, including Faridan region (Փերիա P’eria) and Bourvari. Yet wholesale emigration of some Iranian Armenian villages to Russia in the late 1940s after the Catholicos of Soviet Armenia pleaded to all the faithful to repopulate the ancestral homeland devastated by World War II, famine, and the post-revolutionary atrocities in Russia, still greatly reduced their diversity and numbers. Dialect in Tehran is also delineated along socio-economic lines—although this might be a residual geographic feature—as well as the extent of an individual’s exposure to the Standard Eastern Armenian of post-Soviet Republic of Armenia. Nonetheless, there are a few overarching features of Parskahayeren as encountered in Tehran that have been selected for discussion below.

An Armenian delegation visits the Armenian diaspora community of New Julfa, Isfahan, Iran.

Due to bilingualism and areal features, Iranian Armenian dialects bare typological resemblances to modern Persian, but still markedly less so than other languages spoken in the country (except perhaps the Georgian dialect of Faridan). Pronunciation is a highly distinguishing feature of Iranian Armenian vis-à-vis the Eastern Armenian dialects encountered in the former U.S.S.R. In general, intonation, rhythm and cadence tend to echo Modern Persian—in turn constituting a major deviation from the Caucasian variety, which parallels those features of Russian. For example, the final syllable of interrogative clauses are elongated in the exaggerated manner of Persian and Azeri. The vowel ա “a“ is pronounced like Persian آ “â”, whereas in Yerevan the same vowel is rounded in the manner of Russian “ä“. In general, prosody is used to convey emotions according to the Persian canons; a phenomenon which accounts for the alleged “sing-songy” feel of Parskahayeren according to Caucasian speakers. However, there are still a number of distinct prosodic paradigms in Persian and Parskahayeren that afford the languages quite unique aesthetic qualities. Notably, speakers of Parkshayeren are known to speak rapidly, and tend to employ creaky voice.

Additionally, Iranian Armenian has preserved the Classical alveolar approximant pronunciation of Ր “r”, (which corresponds to the Standard American English pronunciation of “r”); whereas other Eastern and Western Armenian dialects have shifted to alveolar flap [ɾ] (corresponding to the Scottish English pronunciation of “r”). In perfective constructions wherein the verb is not followed by a modifier, the infinitive final -լ -l is dropped: Tehran Vordegh es tsnvé? for Yerevan Ur es tsnvel? “Where were you born?” When the verb is followed by a modifier, Tehran often has -r- final: Tehran eker er for Yerevan yekel er “S/he had come.” In this sense Parskahayeren pronunciation is both archaic and innovative.

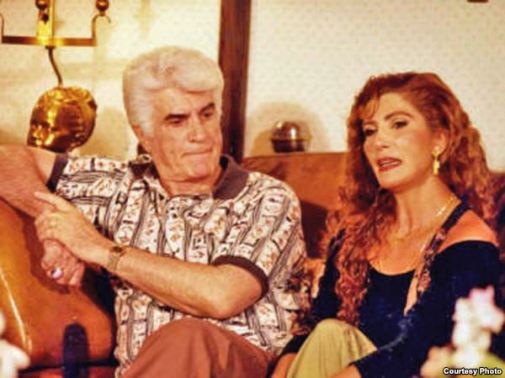

The “Father of Iranian pop music”, Vigen Derderian (Վիգեն Դերդերյան, ويگن دردريان), and his daughter, singer and songwriter Jaklin. Vigen was born into the Armenian community of Hamedan; Jaklin was born and raised in the Armenian community of Tehran.

The Iranian-Armenians are bilingual, although the Tabriz and Urmia communities (Թավրիզ ու Ուրմիայի Հայ համայնքը T’avriz u Urmiayi Hay hamaynk’ё) seem to be operationally trilingual in Armenian, Azeri, and Persian. Bilingualism in the case of fast-paced, trendy Tehran has paved the way for a great deal of code-switching—primarily whereby an Armenian-speaking informant substitutes Persian words in place of their Armenian equivalents. However, the degree of this phenomenon is dependent on the informant and by no means approaches the threshold of creolization. Wholesale substitution of Armenian words is present in the vernaculars of both Tehran and Yerevan (Russian), however markedly more so in the latter, as it appears to be stigmatized in Tehran despite its prevalence:

| English | Standard Eastern Armenian | Colloquial Yerevan (from Russian) | Colloquial Tehran (from Persian) |

| “Generally” | ёndhanrapes ընդհանրապես |

voobshe вообше |

kollan كلا |

| “OK; here you go” | hamets’ek’ համեցեք |

davai давай |

— |

| “Just; just because” | ughghaki ուղղակի |

prosto просто |

— |

| “Because” | vorovhetev որովհետև |

tak kak так как |

chon چون |

| “OK; That’s it” | — | vsyo всё |

— |

| For example; like…” | ōrinak օրինակ |

— | masalan –> “masan” مثلا |

| “So; that is to say; it means; like…; [filter]” | uremn, aysink’n ուրեմն, այսինքն |

to, est’ то есть |

yani يعنى |

| “Already” | arden արդեն |

uzhe уже |

— |

Otherwise, the Tehran vernacular is more conservative in her lexicon compared to the Yerevan vernacular, save a few idiosyncrasies: Tehran esi, esikё and eti, etikё for Standard սա sa “this” դա da “that”; Tehran sté, stegh and ёndé, ёndegh for Standard այստեղ aystegh “here” and այնտեղ ayntegh “there”; Tehran bidi for Standard պետք ե petk’e “must, should”; Tehran esents‘ for Yerevan stents’, nents’ and Standard այսպես ayspes “this way, like this”; Tehran որտեղ vordegh for Yerevan ուր ur “where”; Tehran ira, iran, irank’, irants’ for Yerevan nra, nran, nrank’, nrants’ “his/her, to him/her, they, their”. The issue of Parskahayeren mähät/mät “one; a piece; a little; a moment; a bit; etc.” is discussed below.

For some lexemes, parallel native forms are in use in a manner similar to American English vs. British English, i.e. Tehran: ճարել charel for Yerevan գտնել gtnel “to find”; Tehran: լվացարան lvats’aran for Yerevan լողարան logharan “restroom, washroom”; Tehran օգտվել ōgtvel and գործածել gortsatsel for Yerevan օգտագործել ōgtagortsel “to use”; Tehran: կներեք knerek’ for Yerevan ներողություն neroghut’yun “Pardon me; I’m sorry.”

Iranian-Armenian artist Helen (née Matevosian) sings Garun Yekav (Գարուն Եկավ “Spring Came”), a winner at the 2007 Armenian Golden Star Awards.

Calques from Persian are also pervasive: i.e. վերջացավ գնաց verchats’av gnats’, from تمام شد و رفت tamām shod o raft “It’s over; done for” (literally: “it finished and left”); մեջ տեղից երթալ mej teghits’ ert’al, from از بين رفتن az bayn raftan “to be annihilated; perish”; կարմրացնել karmrats’nel “to fry” (literally: “to redden”) from سرخ كردن sorkh kardan “to fry (redden)”; պատճառ ելնել patch’arr elnel from باعث شدن bāes shodan “to result in; to cause”; տանել tanel “to carry” in the meaning of “to win”, from Persian بردن bordan “to win” (homophone with verb meaning “to carry”); նեղություն քաշել neghut’yun k’ashel from زحمت كشيدن zahmat keshidan “to bare a burden; perform an act of generosity or civility according to local ideals”; Թագավորի ժամանակ T’ak’avori zhamanak from زمان شاه zamāne Shāh “the Pahlavi period; reign of the 20th century Pahlavi monarchs”; մեծ մամ medz-mam and մեծ պապ medz-pap from مامان بزرگ māmān bozorg “grandmother” and بابا بزرگ bābā bozorg “grandfather.” A few calques from Persian phraseology are listed below:

| English | Parskahayeren (colloquial) | Persian (colloquial) |

| “What’s up?/What’s new?” | Inch khabar? Ինչ խաբար? |

Che khabar? چه خبر؟ |

| “Thank you for your service” (literally: “may your hand not hurt”) | Dzerrk’ёt ch’ts’ava Ձեռքդ չցավա |

Dastet dard nakone دستت درد نكنه |

| “Thank you for your exertion” (literally: “may you not be tired”) | Hok’nats chelnes Հոգնած չելնես |

Khaste nabāshi خسته نباشى |

|

“I wouldn’t be so sure” (literally: “my eye doesn’t drink water”) |

Achkёs jur chi khmum Աչքս ջուր չի խմում |

Cheshmam āb nemikhore چشمم آب نمیخوره |

One morphological innovation is addition of a pronominal suffix (-դ -t) at the end of the verbal construction to indicate either the object or indirect object of the verb, and this likely developed under the influence of Persian. This is unusual for Armenian, which employs a stringent case system. Nonetheless it is prevalent in generation Y’s vernacular and is only used when the 2nd person is the object or direct object of a clause:

| English | Tehran (contracted form) | Yerevan (invariable) |

| “I’ve missed you” | karotel emët | karotel em k’ez |

| “I am waiting for you” | spasum emët | spasum em k’ez |

| “Let me tell you something…” | me ban asemët… | mi ban k’ez asem… |

Sometimes parallels are encountered to Persian compound verb construction: i.e. [Persian/Armenian gerund] + [Armenian helping verb]; the latter is usually անել anel (for كردن kardan) “to do”, խփել khp’el (for زدن zadan) “to hit”, վերցնել verts’nel (for گرفتن gereftan) “to get”, բռնել brrnel (for گرفتن gereftan “to hold”). Such as chort khp’el (from چرت زدن chort zadan) for Yerevan նիրհել nirhel “to take a nap”; pakhsh anel (from پخش كردن pakhsh kardan) for Yerevan հաղորդել haghordel “to broadcast”; պտույտ խփել ptuyt khp’el (from چرخ زدن charkh zadan) for զբոսնել zbosnel “to take a stroll”; դուշ բռնել dush brrnel (from دوش گرفتن dush gereftan) for Yerevan լողանալ loghanal “to take a shower.”

Tehran կարողանալ karoghanal + conj. subjunctive verb (parallel to Western Persian construction) for Yerevan karoghanal + infinite verb “to be able to do [something]”; Չեմ կարող ասեմ Chem karogh asem for Yerevan Չեմ կարող ասել Chem karogh asel “I cannot say”, among many other examples.

Iranian-Armenian Bible study talk show, “Good News” (Բարի Լուր), produced by the Iranian-Armenian diaspora in California

Parskahayeren shares a number of core lexical items with Western Armenian, her distant cousin, vis-à-vis the Eastern varieties found in the former U.S.S.R. Most notably, Tehran has երթալ ertal for Yerevan գնալ gnal “to go”; իմանալ imanal for Yerevan գիտել gitel “to know”; ելնել elnel for Yerevan լինել linel “to be”; հէր her for Yerevan խի khi/ինչու inchu “why”. Parskahayeren sometimes also shares the added -ի -i ending encountered in the Western Armenian pronomial dative construction: Tehran ինձի indzi, քեզի k’ezi, etc. for Yerevan ինձ indz քեզ k’ez “to me, to you”. Some of these lexical differences are illustrated below:

| English | Tehran | Yerevan |

| “I don’t know” | չեմ իմանում Chem imanum |

չգիտեմ Ch’gitem |

| “What’s happened?” | Ինչ ա ելե? Inch a elé? |

Ինչ է եղել? Inch e yeghel? |

| “Why didn’t he give you an apple?” | Հեր քեզի խնձոր չտվավ? Her k’ezi khndzor ch’tvav? |

Ինչու քեզ խնձոր չտվեց? Inchu k’ez khndzor ch’tvets’? |

A multitude of -եց ets’-class verbs are -ավ av-class in Tehran, which resembles the pattern in Western Armenian. In this paradigm, Tehran has -ամ -am for the 1st person register, which likely developed under influence of Persian, whereas Yerevan has -ա –a; i.e. Tehran տեսամ tesam for Yerevan տեսա tesa “I saw.” Sometimes -ել –el infinitives are –ալ –al in Iran, i.e. khosalu en “they will speak” for Yerevan խոսելու են khoselu (y)en. For example, ասել asel “to say” and տալ tal “to give”:

| English | Tehran (spoken) | Yerevan |

| I said, gave | asam, tvam ասամ, տվամ |

asets’i, tvets’i ասեցի, տվեցի |

| You said, gave | asar, tvar ասար, տվար |

asests’ir, tvets’ir ասեցիր, տվեցիր |

| S/he said, gave | asav, tvav ասավ, տվավ |

asests’, tvets’ ասեց, տվեց |

| We said, gave | asank’, tvank’ ասանք, տվանք |

asests’ink’, tvets’ink’ ասեցինք, տվեցինք |

| You (pl.) said, gave | asak’, tvak’ ասաք, տվաք |

asests’ik’, tvets’ik’ ասեցիք, տվեցիք |

| They said, gave | asan, tvan ասան, տվան |

asests’in, tvets’in ասեցին, տվեցին |

The 1st person -մ -m ending is also encountered in the past imperfective construction composed of [elnel (to be) + present participle] as well as the past subjunctive. This is also unique to Parskahayeren in the Eastern group:

| English | Tehran (spoken) | Yerevan |

| “I wanted to understand, but I couldn’t be quiet” | Uzum im haskanaim, bayts chim karogh lrrem | Uzum ei haskanai, bayts chei karogh lrrel |

| “I was walking in the street, when suddenly someone called out to me from afar and approached” | K’aylum im p’oghots’um erb hankarts mekё‘ herrvits’ kanchav indzi u motets’av | K’aylum ei p’oghots’um yerb hankarts mekё herrvits’ kanchets’ indz u motets’av |

The issue of “mähät” or “mät” (from մի հատ mi hat “one piece“) in Parskahayeren is particularly unusual in that this lexeme has introduced a new vowel phoneme to the Iranian Armenian system (namely, ä). The contexts for its use are ambiguous and abstract:

| Iranian Armenian | English |

| Mät ari ste | “Come here for a moment” |

| Mät hangstats’ru senyakumët | “Rest for a while in your room” |

| Mät indzi tur | “Give me one [piece]” |

| Vaghë kertam khanut’its’ mät khaghalik’ verts’nem ira zavakneri hamar | “Tomorrow I’m going to go pick up a toy for his children from the store” |

| Mät mtats’ir myusi zgats’munk’neri masin | “Think a little bit about the other person’s feelings” |

A young Circassian in Maykop, capital of the Republic of Adyghea, Russia. In recent years the republic has experienced a deepening interest in the descendants of Circassian deportees abroad, often pleading to the diaspora to repopulate their historic homeland in light of upheavals in the Near East.

A young Circassian in Maykop, capital of the Republic of Adyghea, Russia. In recent years the republic has experienced a deepening interest in the descendants of Circassian deportees abroad, often pleading to the diaspora to repopulate their historic homeland in light of upheavals in the Near East.