Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This article surveys the Iranian presence in pre-Islamic Arabia and the medieval Islamic world and addresses Classical Arabic loans in Modern Persian. It features an exclusive English-language appendix of 200 Middle Iranian loans into Classical Arabic and their etymologies, compiled by the author.

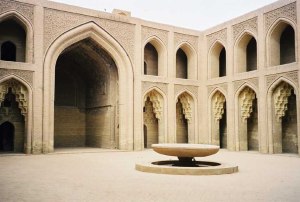

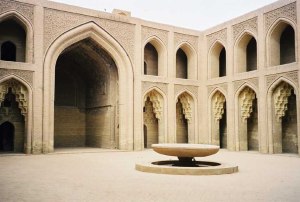

A library in present-day Baghdad with the Persian four-ayvān courtyard scheme, named after Bayt al-Ḥikma; courtyard view, Abbasid-era portion.

On the Prevalence of Classical Arabic Loanwords in Modern Persian

Whereas pre-Islamic Iranian languages are virtually free of Semitic vocabulary, Aramaic, Syriac, Hebrew, and Arabic have borrowed a remarkable number lexical items from Iranian (as did late Babylonian, Achaemenid Elamite, Old Armenian, and Georgian). Historical linguists have afforded the majority of these languages comprehensive pedigrees of Iranian borrowings, but regrettably few authors have paid attention to the Iranian loans in the Arabic language and literature, and in doing so, have neglected a rich narrative of cultural contact whereby Persian and Byzantine antecedents formed the creative backbone of early Islamic material and visual culture.

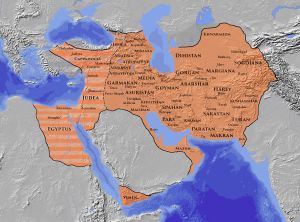

The Sassanid Empire (224 A.D.-651 A.D.) was the last Zoroastrian Iranian polity before the arrival of Islam. Sassanian and Byzantine antecedents formed the creative backbone of early Islamic material and visual culture.

It is no mystery that following the conquest and Islamization of Sassanid Persia throughout the 7th and 8th centuries A.D., Iranian languages were shot through, even to the most far-flung dialects, with Arabic loanwords. Yet Arabic never attained currency as a lingua franca in the Iranian world. Instead, knowledge of the Classical Arabic language throughout the Islamic period was limited to educated city-dwelling Muslim circles, and it was from this stratum of society that Classical Arabic lexica were gradually and purposefully incorporated—often undergoing abstract semantic shifts—into “erudite speech”, which became the basis of New Persian literature, scholarship, and poetry. These Iranian religious figures, literati, linguists, poets, historians, mathematicians, chemists, alchemists, astronomers, physicians, geographers, musicians, and philosophers became preeminent contributors to the canonization of the Arabic language and its transformation from a regional nomadic tongue into a universal vehicle of both doctrinal and secular learning. Acculturation was taking place along the same vector– whereby medieval Islamic architecture, horticulture, cuisine, attire, court culture, political offices, etc. were systematically appropriated from earlier Persian and Byzantine models.

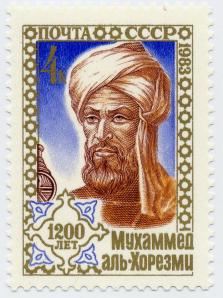

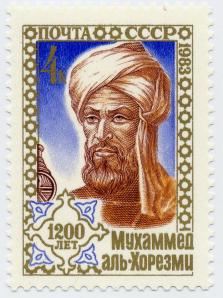

Al-Khwārizmi was an Iranian mathematician, astronomer, and geographer during the Abbasid Caliphate. The English word “algorithm” is his namesake, and the word “algebra” derives from al-jabr, an operation he used to solve quadratic equations. Here he is pictured on a postal stamp issued by the USSR in 1983 (left) and immortalized in statue form at Khiva, Uzbekistan (right).

Knowledge of Classical Arabic was essential and indispensable for religious worship, and the correct reading of the Qur’an was impossible without it. But in the first century of Islamic ascendancy, the Arabs did not produce anything of literary value. If any poetry was composed, it was on the old pagan models and celebrated the poets’ amatory adventures, in stereotyped fashion, rather than the victories of Islam. As Reinhart Dozy notes:

Mais la conversion la plus importante de toute fut celles des Perses. Ce sont eux, et non les Arabes qui ont donné de la fermeté et de la force à l’Islamisme, et en même temps, c’est de leur sein que sont sorties les sectes les plus remarquables. (Dozy, L’Islamisme, p. 156)

It follows that the first grammar of the Arabic language, al-Kitāb (الكتاب), was written by the Persian author Sībūyeh (سيبويه; Arabic: Sībawayh) in the 8th century AD. Many of his Iranian contemporaries with masterful command of Arabic, including Ibn al-Muqaffa’, translated thousands of Indian, Greek, Syriac, and Persian literary works from Middle Persian into Classical Arabic. The epicenter of these intellectual activities was Bayt al-Ḥikma (بيت الحكمة; literally “House of Wisdom”) in Baghdad, which was the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma’mun’s appropriation of the Sassanid Persian Academy of Gundishāpur, the world’s first center of both religious and secular higher-learning. The Caliph had the contents of Gundishāpur and its world-renowned hospital transported en masse to Bayt al-Ḥikma, which was staffed by graduates of the Academy of Gundishāpur and wherein the methods of the older Persian academy were to be emulated. The Bukhtishu-Gundishāpuri family were Nestorian physicians from this university in Persia who served at the Abbasid court through the 7th, 8th, and 9th centuries, spanning six generations. The Caliph al-Mansur’s new capital and crown jewel, Baghdad (“God-Given” in Middle Persian), was no exception to this trend; the city had been modeled on the quintessential Sassanid round city plan (such as at Firuzābād) by a Persian architect and planner, Mashallah ibn Athari, and the astrologically-auspicious location for the imperial city had been chosen by none other than Nawbakht, a Zoroastrian priest. The Abbasid and Fatimid bourgeoisie were patrons of Persian garments, etiquette, court culture, and cuisine, and relied heavily on Persian viziers such as the Barmakid family (برمكيان) to oversee crucial matters pertaining to finance and state administration. As such, they adopted the Sassanid postal system and bureaucratic system (ديوان diwān).

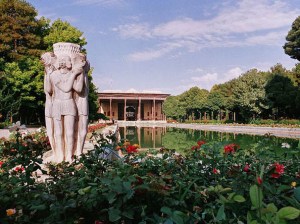

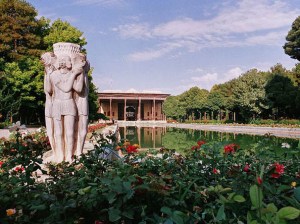

Persian gardens (top) have influenced the design of gardens from Andalusia to India and beyond. The gardens of the Alhambra show the influence of Persian Garden philosophy and style in a Moorish Palace scale, from the era of Al-Andalus in Spain (bottom).

Persian influence increased at the Court of the Caliphs, and reached its zenith under al-Ḥādi, Harun al-Rashid, and al-Ma’mun. Most of the ministers of the last were Persians or of Iranian extraction. Afshīn Kheydār b. Kāvūs, the all-powerful favorite of the Caliph al-Mu’tasim and a scion of the Buddhist princes of Osrushana in modern-day Uzbekistan, was appointed Abbasid Supreme General and Governor of Sindh, Jebāl, Libya, Armenia and Azerbaijan. In Baghdad, Persian fashions continued to enjoy an increasing ascendancy, and the old Persian festivals of Nowruz and Mihrigān (origin of the modern Arabic مهرجان mahrajān “festival, celebration”) were celebrated. Persian raiment was the official court dress, and the tall black conical Persian hats (qalansuwa) were already prescribed as official by the second Abbasid caliph in 770 A.D. At the court, the customs of Sassanians were imitated and garments decorated with golden inscription were introduced which it was the exclusive privilege of the ruler to bestow.

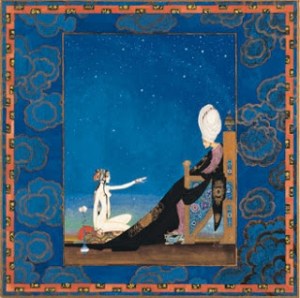

The Islamic Golden Age reached its peak during the 10th and 11th centuries, during which Persia was the main theater of academic activity, eclipsing al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) in volume and significance. Persian scholars and polymaths in various fields produced their masterpieces in Arabic—an Arabic whose lexicon they had made applicable to their respective fields in pioneer ways and for which they had popularized new phraseology, word forms, and grammatical structures through the dissemination of their works. Among the most prominent of these individuals were al-Khwārizmi, Abu Sinā (Avicenna), al-Tusi, al-Biruni, Omar Khayyām, al-Haitham, al-Shirāzi, and Nāṣer Khusraw. Ironically, one can imagine that a rather pure, literary Classical Arabic vernacular was probably in use among Iranian scholarly circles in Khorāsān and Khwārezm (a historic Iranian region roughly corresponding to modern day Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan) during the Abbasid period, while the vernaculars spoken in major Arab-inhabited urban centers around the realm such as Baghdad, Damascus, and Cordoba were of colloquial provenance and were undergoing gradual deviation from Classical pronunciation, grammar and lexicon under the influence of regional linguistic factors. These colloquial transformations are reflected in contemporary literary productions such as 13th century manuscripts of “1001 Nights” (Arabic: الف ليلة و ليلة Alf Leyla wa Leyla, based on an earlier Persian work Hazār Afsāna, literally “1000 Myths”) recovered from Syria and Egypt.

The story of “1001 Nights”, also popularized under an orientalist misnomer “Arabian Nights”, is a series of adapted stories based on a mythical Persian king Shahryār and a storyteller Shahrzādeh. The core characters and structural framework of the Arabic language version are inextricably akin to an earlier Persian work, Hazār Afsāna, with the addition of a few Arabic given names, Abbasid-era stories and motifs such as the Jinn.

This trend did not escape the observation of the 14th century Arab historiographer, Ibn Khaldun, who elaborately explains the primacy of Iranian culture and learning in the nascent Islamic world:

It is a remarkable fact that with few exceptions, most Muslim scholars…in the intellectual sciences have been non-Arabs. Thus the founders of grammar were Sibawayh and after him, al-Farisi and Az-Zajjaj. All of them were of Persian descent…they invented rules of (Arabic) grammar…great jurists were Persians… only the Persians engaged in the task of preserving knowledge and writing systematic scholarly works. Thus the truth of the statement of the Prophet becomes apparent, ‘If learning were suspended in the highest parts of heaven, the Persians would attain it…The intellectual sciences were also the preserve of the Persians, left alone by the Arabs, who did not cultivate them…as was the case with all crafts…This situation continued in the cities as long as the Persians and Persian countries, Iraq, Khorasan and Transoxiana (modern Central Asia), retained their sedentary culture. [Translated by F. Rosenthal (III, pp. 311-15, 271-4 [Arabic]; Frye, R.N. (1977). Golden Age of Persia, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p.91)].

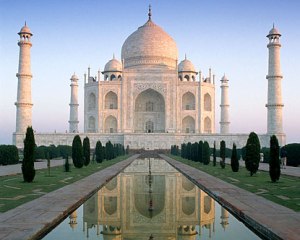

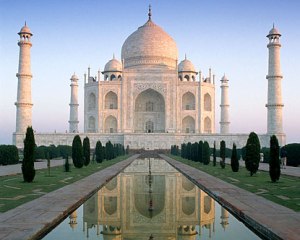

Mughal India, like the Ottoman Empire and the Timurid Empire, was a Persianate society (a society that is either based on, or strongly influenced by the Persian language, culture, literature, art, and/or identity.). Emperor Shāh Jahān (literally “King of the World” in Persian), commissioned a Persian architect from Badakshān named Ustād Ahmad Lāhauri to construct the Tāj Mahal (“Crown Place” in Persian) for his Persian wife and lover, Mumtāz Mahal (née Arjumand Banu Begum.) The Taj Mahal is one of the largest Persian Garden interpretations in the world.

It was via this initially exclusive medium of scholarly and artistic expression promulgated by Muslim Iranian intelligentsia that Middle Persian transformed into New Persian in the urban centers of Khorāsān, Khwārezm and Transoxiana throughout the early Islamic period. Many Middle Persian words were rendered archaic and thence obsolete in favor of abstract Classical Arabic loanwords–a feature that was characteristic of the speech of the Muslim Persian city-dwelling elite. A modified Arabic orthography was applied to this transforming tongue in place of the Pahlavi scripts used to record Middle Persian. This new form of the Persian language became a prestige dialect throughout the Iranian world, spreading from Central Asia throughout the Iranian plateau, and would later enjoy widespread patronage and even official currency in the royal courts of the Ottomans, the Timurids, and the Mughals in India. What are modern-day Turkey and the Indian subcontinent even became important centers of Persian literary and poetic production. In Persianate societies, Arabic words were indirectly transmitted via Persian influence into languages such as Urdu, Turkish, Uzbek, Azerbaijani, Kurdish, Turkmen, Pashto, Uyghur, as evidenced by the retention of Persian phonological modifications to Classical Arabic pronunciation in these languages. Sarti Uzbek (but not Khorezmian or Kipchak Uzbek) even lost vowel harmony—a rudimentary feature of Turkic phonology—as a result of Persian substratum and bilingualism.

But this was by no means the first golden age for the Persian language—pre-Islamic Iranian languages likewise exerted a remarkably pervasive influence on neighboring tongues under the aegis of Iranian suzerains and civilized elite in those territories. Classical Armenian contained an impressive sixty percent of its general vocabulary derived from Iranian languages, and most Aramaic languages had been heavily Persified by the time of the Islamic conquest—even serving as media of transmission for Iranian borrowings into Arabic.

[From top, left-right: 1. Chahār Minār, Bukhara 2. Bukhara, view of old city and wall 3. Nādir Divan-Begi Khānaqāh, a Sufi monastery featuring depictions of Simurgh from Ferdowsi’s Shāhnāmeh on its pishtaq, Bukhara 4. Bālā-Hauz, Bukhara 5. Gūr-i Amīr, Tamerlane’s mausoleum, Samarqand 6. Rēgistān square, Samarqand 7. Shāh-i Zinda, Samarqand 8. Shērdār Madrasa at Rēgistān, Samarqand]

Bukhara and Samarqand are still natively Persian-speaking (Tajik) cities in modern-day Uzbekistan; the former traditionally boasted a sizable Persophone Jewish element as well that has since relocated to Israel. The structures depicted are architectural heirlooms to the region’s robust Persianate past and former economic prosperity under the Samanid, Ghaznavid, and later Timurid empires. From a philological standpoint, we can imagine that it was in urban centers like these that incoming Turcophone groups interacted with the autochthonous settled Persian-speaking populations in Transoxiana, in turn giving rise to the modern Uzbek yoke, and wherein the Uzbek language (Sart dialect; progenitor of the modern literary language) gradually lost features typical of Turkic—notably the vowels /ü/, /ö/ and vowel harmony—and adopted thousands of Persian words and phrases. (*note the Khorezmian Uzbek language is of Oghuz provenance but features a heavy admixture of Uyghur-Uzbek elements; the Kipchak Uzbek language is closely related to Kazakh. Both of these languages are vowel-harmonized and feature relatively fewer Persianisms in their lexicon and morphology)

Thus the prevalence of Classical Arabic loanwords in New Persian is largely the fruit of a medieval scholarly tendency among Iranian intelligentsia who composed their works in Classical Arabic to then incorporate Arabic words and phrases into their speech, perhaps in an attempt to “enrich” the non-Islamic Middle Persian tongue and thereby emphasize their elevated stratum in society (city-dwelling, educated Muslim families) on the basis of their prestigious vernacular. Iranian scholars and polymaths also played a pivotal role in the standardization and diffusion of Classical Arabic, and Persians, Greeks and Syriacs served as cultural brokers in the Abbasid court.

Persian Islamic Scholars Composed All Six of the Major Sunni Hadith Collections (al-Kutub as-Sittah)

During the 9th century, all of the six canonical collections of the Sunni ḥadith, venerated by Sunni Muslims as al-Kutub as-Sittah (الكتب الستة) and second in importance only to the Quran, were composed by Persian authors. Their names and places of origin are listed below:

1. Sahih Bukhari, collected by Imam Bukhari (d. 256 AH, 870 CE), born in Bukhārā

2. Sahih Muslim, collected by Muslim b. al-Hajjaj (d. 261 AH, 875 CE), born in Nishāpur, Khorāsān

3. Sunan al-Sughra, collected by al-Nasa’i (d. 303 AH, 915 CE), born in Nisā, Khorāsān

4. Sunan Abu Dawood, collected by Abu Dawood (d. 275 AH, 888 CE), born in Sistān

5. Jami al-Tirmidhi, collected by al-Tirmidhi (d. 279 AH, 892 CE), born in Termez, Khorāsān

6. Either:

Sunan ibn Majah, collected by Ibn Majah (d. 273 AH, 887 CE), born in Qazvīn

Sunan ad-Dārimī , collected by Imam Al-Darimi (181H–255H), born in Samarqand

List of Middle Iranian Loanwords in Classical Arabic (Compiled by the Afsheen Sharifzadeh)

Ahmad Amin writes “at a glance one can see that the Arabs in every point or every way they turned or for every necessity of life were obliged to use Persian words. Besides the words themselves they adopted the phrase-making ideas and expressions used by the Persians in explaining various matters or in defining things.”

Hundreds of Iranian words and terms began to enter into Arabic language, sometimes via an Aramaic milieu, and were Arabicized (تعريب ta’rīb) in eccentric ways according to the phonetic and morphological system of that language. Verb derivatives were even formed from Iranian nouns according to the Arabic patterns (اوزان awzān). It follows that Iranian lexical borrowings in Classical Arabic (معربات mu’arrabāt) pertained to all domains of civilized society, including botany, culinary matters, administration, architecture, minerals, philosophy, zoology, musical instruments, and items of luxury and power adopted from Sassanian Persia. The following are some notable and readily-recognizable Eastern Iranian/Parthian, Middle Persian (MP) loans, and Early New Persian (NP) that remain in Modern Standard Arabic (اللغة العربية الفصحى) as well as most dialects, although borrowings in Classical Arabic and Mesopotamian/Gulf dialects are more varied and numerous.

LIST

abad- eternity (MP: a-pād “without foot, endless”)

‘abqari- genius, highest perfection, unsurpassed (MP: abargar “superior, highest”)

adab– literature; courtesy, civility (constructed from MP: dab)

‘anbar- ambergris (MP: hambar)

anbār– warehouse, depot (MP: hambār)

argīla– waterpipe (NP: nārgīl “coconut”)

‘askar, ‘askari- army, military (constructed from MP: lashkar)

‘aṭr, ‘aṭṭar, mu’aṭṭar– perfume, perfumist (constructed from MP: atr)

azraq, zarqā’- yellow (constructed from MP: zargōn “golden”)

Baghdād (MP: baga+data “Given by God”)

bahlawān- clown, gymnast (MP: pahlawān “champion”)

bakht- luck (from MP: bakht)

banafsaj- purple, violet (MP: wanafshag, NP: banafsha)

bandar– port, harbor (MP: bandar)

baqshish- tip, gratuity (MP: bakhshish “gratuity”)

bāriz, baraza– prominent; to elevate (constructed from MP, Parthian: borz “high; elevate”)

barīd– post, mailing (constructed from MP: burida-dum “a docked mule appointed for the conveyance of messengers”)

barnāmaj- program (MP: abarnāmag)

bas- (coll.) but, enough, stop (NP: bas)

bashkīr– hand towel (MP: pēshgir)

bathinjān- eggplant (MP: bādengān)

baṭṭ– duck (MP: bat)

bayān- statement, report, accouncement (MP: payām)

baydaq– a footman [in chess] (constructed from MP: payādag, NP: piyāda)

bulbul- bird (MP: bulbul)

bulūr- crystal (MP: bolur)

bunduq– hazelnut (MP: pondik)

bunj- anaesthetic (MP: pōng)

burj– tower (MP: burg)

burwāz- frame (MP: parwast “enclosure”)

bustān- garden (MP: bostān)

bāmiya- okra (MP: bamiya)

bārija- battleship, flagship (MP: bārūja “flower pot”< “a deep-hulled vessel”)

bāzār– market (Parthian: wahāchār, MP: wāzār, NP: bāzār)

būsa- kiss (MP: bōs)

dabīr, dabbara- manager; to oversee, plot (constructed from MP: dipīr)

daftar- notebook, office (MP: dabtar)

darb- gate (MP: darpân “gatekeeper”, Arabic reflex of this term)

darwīsh- ascetic, particularly Sufi (MP: dreyosh “one who lives in holy indigence”)

dashin, yadshin– dedicate (constructed from MP: dashn “gift”)

dumbek– drum (MP: tumbag)

dukkān– shop (MP: dukan)

dulāb– wheel (MP: dol-ab “water wheel [machine]”)

dunyā- world (MP: dunya)

dustūr- constitution (MP: dastwar, NP: dastūr)

dīn, diāna, tadayyun- religion, piety (constructed from MP: dēn> OP: daēna)

dīnār– unit of currency (MP: denār)

dīwān- high governmental body, council (MP: dēwān “archive”)

falak- orb, sphere (MP: parak “the star Canopus, brightest star”)

Fārsī, Bilād al-Furus– Persian, Persia (MP: Pārsīg)

fattash, taftīsh, mufattish- inspect (constructed from MP: pitakhsh “viceroy”>p-t-kh-sh>f-t-sh)

fayj– courier (MP: payg, NP: payk)

fayrūz- turquoise (MP: pērōzag, NP: firuza)

fihris, fahrasa- index, register (constructed from MP: pahrist)

finjān- cup (MP: pengân)

firdaws- paradise (MP: pardēs)

fiṣfiṣa- alfalfa (MP: ispist)

fustuq- pistacchio (MP: pistag)

fīl- elephant (MP: pil)

filfil– pepper (MP: pelpel)

fūlādh– steel (MP: polad)

fūṭa- towel (MP: pusha)

handasa, muhandis- engineer (constructed from MP: [h]andāzag “measure, quantity”, NP: andāza)

hawā’- air, atmosphere (MP: havā> OP: hvayāv “good current”)

haykal- framework, outline (MP: paykar)

Hind- India (Persian name for Sindh, product of h>s Iranian/Indo-Aryan isogloss)

hindām– symmetry (MP: [h]andām “symmetry, arrangment”)

ibrīq- jug (MP: abrēk)

īwān- a chamber or vault, often at the exterior entrance of a building (MP: aywān)

jāmūs– buffalo (MP: gāwmēsh)

janzīr– chain (MP: zanjīr)

jaṣṣ, jaṣṣās- gypsum; plasterer (MP: gach)

jawhar- essence, substance (constructed from MP: gōhr)

jawhara, jawahir- jewel (constructed from MP: gōhr)

jawz- walnut (MP: gōz)

jazar– carrot (MP: gazar; descendents Larestani: gazrak, Armenian: gazar))

jund, jundīyya, tajannud, tajnīd- army, military service, enlistment (constructed from MP: gund “army”)

jāsūs, tajassus- spy, espionage (constructed from MP: goshash>g-sh-sh>j-s-s, “hearer, listener”)

julnār- pomegranate blossom (MP: gulnār)

jūrāb- socks (NP: jawrāb)

ka’ak– a type of pastry (MP: kāk)

kabāb, kubba- roasted meat on skewers (MP: kabāb)

kahrabā’- electricity (MP: kāhrubā, “yellow amber”)

kamān, kamānja- a musical instrument (MP: kamān “bow”, kamāncha “little bow”)

kānūn- campfire, furnace (MP: kānun)

kanz- treasure (MP: ganj>OP: ganza)

khām- raw [materials], ore (MP: khām “raw, crude”)

khandaq- moat, pit (MP: kandag)

khanjar- dagger (MP: khōngar)

kharj, kharrāj– tribute, duty, work (constructed from MP: harg)

khiār- cucumber (MP: khyār)

khurda- scraps, fragments (MP: khurdag)

khammana, takhmin- guess, speculate, value (constructed from MP: gumān g-m-n > kh-m-n)

khān- shelter, rest stop (MP: khān “house”)

khashin, khushūna- rough, harsh; severity (constructed from MP: khashen)

khazīna, makhzan- treasury (constructed from MP: ganjēna g-j-n > kh-z-n)

kīmīā’– chemistry (MP: kimiā)

kīs- bag (MP: kisag)

kisra- idol (from MP: Kasra, Khosrow)

kūz- vase, storage vessel (MP: kōz)

laymūn: lemon (MP: lēmōg)

lāzaward: lapis lazuli (MP: lajward)

lubiya- bean (MP: lobiya)

mahara, muhr- stamp, seal (MP: muhr)

mahrajān- festival (MP: Mihrigân, Zoroastrian autumnal equinox celebration)

al-Māristān– premier hospital complex of Abbasid-era Baghdad (from MP: wēmāristān; NP: bimārestān)

marj – field (Parthian: marg, MP: marv)

marjān- pearl, coral (MP: margān)

mās– diamond (MP: almās)

masaka, massaka, amsaka, tamassak– adhere, stick, cling, take hold (constructed from MP: mashk “musk”)

mask– musk (MP: mashk)

mawz– banana (MP: mōz)

maydān- city square, field (MP: mēdān)

mezza– taste, starter (MP: mizag, NP: mazza)

mihrāb- niche in the wall of mosque indicating the qibla or direction of Mecca (MP: Mihrāba “Mithraeum”)

miswāk– toothpick, toothbrush (constructed from MP: sawāk, from MP sūdan “to rub, scrape”)

muzarkash, zarkash- colorful, decorated (constructed from MP: zarkesh “gilded”)

nabāt- sugar crystals, “sugar candy” (MP: nabat)

nabīdh– wine (MP: nabēd)

nadhar, intidhār, munādhir, mandhūr– to look, watch, wait (constructed from MP: negar, negaristan)

nafṭ– oil, petroleum (MP: naft)

namr- cushion, pillow (Parthian: namr “meek”, NP: narm)

naqsh, munāqasha, niqqāsh, naqqāshi, manqūsh- painter, artist (constructed from MP: nakhsh)

narjis- narcissus flower (MP: nargis)

nasrīn- sweetbriar flower (MP: nasrēn)

nishān- badge (MP: nishan)

numūdhaj- exemplary (MP: namudag)

nākhudhā- ship captain (MP: nāv-khudā)

nāranj: orange, clementine (MP: narang)

nāy: reed flute (MP: nay)

nīlūfar: nenuphar, lotus, water lily (MP: nilōpal)

qabr- grave, coffin (MP: gabr “hollow, cavity”)

qafaṣ– cage (MP: kafas)

qahramān- champion (MP: kār-framān, “manager, overseer”)

qas’a- serving pot (MP: kāsa)

Qazwīn- Caspian (MP: Kasbīn)

qirmiz– crimson, scarlet (MP: kermest)

qubba- vault, dome, cupola (MP: gunbad)

qumbula- bomb (MP: kumpula)

raṣāṣ– lead, tin (constructed from MP: arziz > Parth: archich)

rizq, razaqa, istarzaqa, rezzāq- daily wage, sustenance; to bestow or endow (constructed from MP: rōzig, Parthian: rōchik “daily bread”)

ṣaidala, ṣaidaliyya– pharmacy (constructed from MP: chandal “sandalwood”)

ṣaqr- hawk (MP: chark)

ṣalīb- cross (MP: chalipa)

ṣandal- sandals, sandalwood (MP: chandal “sandalwood”)

ṣandūq– chest, crate; treasurer’s office (MP: sandūk)

ṣanj– harp (MP: chang)

sarādiq- pavillion, canopy (MP: srādag)

sardāb- basement (MP: sardāba)

sarīr- throne, bed (MP: sarir)

sawsan– lily (MP: sōsan)

shakush- hammer (MP: chakuch)

shāhīn- falcon (MP: shāhēn)

shatranj- chess (MP: chatrang)

shā’ib, shā’ibа, ashīb – grizzly (constructed from MP: āshub)

shāwīsh– sergeant (MP: chāwush “seargent, herald; the leader of a caravan”)

shāy- tea (MP: chāy)

shibbith– dill (MP: sheved)

shīsha- waterpipe (NP: shīshag “bottle, flask”)

siāl, sayl, musīl– flowing, runny (constructed from MP: sayl, i.e. saylāb)

sifir- zero (MP: zifr)

simsār, samsara- middleman, broker (MP: samsar)

sirāj- lamp, light (MP: chirāgh)

sirāṭ– path, way, custom (MP: srat, “street”)

sirdāb- tunnel, cellar (MP: sardāb)

sirwāl- pants, trousers (MP: shalwār)

sufra- dining table (MP: supra)

sukkar- sugar (MP: shakar)

Aṣ–ṣīn- China (MP Chin, name for China, from the Qin dynasty)

sādej- plain, simple (MP: sādag)

sīkh- skewer (MP: sikh)

ṣīnīyya- tray (MP: chini, in reference to imported chinaware from the East)

sīra: juice (MP: shirag)

ṭabaq- plate, dish (MP: tābag “frying pan”)

ṭābūr- line, queue (MP: tabur)

ṭarāz- type, brand (MP: taraz)

ṭarbūsha– a type of hat, “red fez” hat (NP: sar “head” + pūsh “wear”)

takht, takhta- platform, bench (MP: takht “throne”)

tanbal- lazy (MP: tanparvar)

tannūr- oven (MP: tanūr)

tannūra- skirt, dress (MP:tanvar)

tarjuma, mutarjim– translation (constructed from MP: targumān)

tarzī- tailor (MP: darzi)

tāj- crown (MP>Parthian: tāg)

ṭāzej– fresh, new (MP: tāzag)

tūt- mulberry, berry (MP: tut)

ustuwāna- disc, cylinder (NP: ostovāna)

ustādh- teacher, master (NP ostād>MP: avistād “master, skillfull man”)

waqt- time (from Parthian, Eastern M.Irn: bakht)

ward, warda- flower, rose (Parthian: ward, Early MP: varda> OP: varda)

wazīr, wizāra- vizier (MP: vichira “bureaucrat, member of Sassanian court”)

yasmīn- jasmine (MP: yasmēn)

yāqūt- ruby (MP: yākand)

Yūnān- Greece (MP: Yonan, Persian name for Ionia)

za’farān– saffron (MP: zarparōn)

zaman, zamān- time [abstract] (MP: zamān, zamanāg, Parthian: zhamān, zhamānak)

zandīq- heretic (MP: zandik)

zanjabīl- ginger (MP: singibir)

zayt, zaytūn– olive (MP: zayt)

zilzāl- earthquake (MP: zilzilag)

zinzāna- prison, dungeon (MP: zindānag)

zumurrud– emerald (MP: uzumburd)

Persian Factors in pre-Islamic Arabia and the days of the Prophet Muhammad

The contacts between Arabia and the Sassanian Persian Empire were very close in the period immediately preceding Islam. The Arab Kingdom centered at al-Hira on the Euphrates had long been under Persian influence and was a headquarters for the diffusion of Iranian culture among the Arabs. Throughout the titanic struggle between the Sassanids and the Byzantine Empire, where al-Hira had been set against the Kingdom of Ghassan, other Arab tribes became involved in the conflict and naturally came under the cultural influence of Persia. The Court of the Lakhmids at al-Hira was in pre-Islamic times a famous center of literary activity, and Christian poets such as Adi ibn Zaid lived long at this court and produced poems containing extensive Persian loanwords. But the Iranian influence was not merely felt along the Mesopotamian areas; it was an Iranian general and Iranian influence that overthrew the Abyssinian suzerainty in southern Arabia during Muhammad’s lifetime.

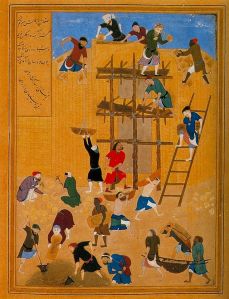

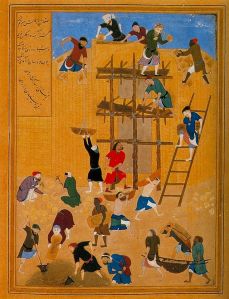

A Persian manuscript from the 15th century describing the construction of Al-Khornaq castle In Al-Hira, the Arab Lakhmids’ capital city. The Lakhmids were a Christian Arab tribe of Yemenite stock who established their center in southern Iraq in 266 A.D., near the Sassanid capital of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.

In the early days of the Prophet’s mission, there were only seventeen men in the tribe of Quraysh who could read or write. It is said that an Iranian man, known as Hammad ar-Rawiya, seeing how little the Arabs cared for poetry and literature, urged them to study poems. In fact it was Hammad who selected the Mu’allaqāt, the seven Arabic poems written in pre-Mohammedan times and inscribed in gold on rolls of coptic cloth and hung up on the curtains covering the Ka’aba. In this period, Hammad knew more than any one else about the Arabic poetry. According to Edward Browne, before the advent of Islam, the Arabs had a negligible literature and scant poetry. It was the Iranians who after their conversion to Islam, feeling the need to learn the language of the Qur’an, began to use that language for other purposes.

Ph. Gignoux hypothesizes that the Quranic phrase bismi’llahi’l-rahmani’l-rahim was modeled on the Middle Persian pad nam-i yazdan. Although there were antecedent Jewish and Christian parallels, a similar formula was also current among Zoroastrians and Manichaeans.

In The Vocabulary of the Quran, Arthur Jeffrey enumerates over 40 words of Iranian origin in Qur’an, among them the following: ebriq, estabraq, barzakh, burhan, tanur, jizya, junah (from gonah), dirham, din, dinar, rezq, rauza, zabania, zarabi, zakat, zanjabil, zur, sejjil, seraj, soradaq, serbal, sard and zard, sondos, suq, salaba, ‘abqari, efrit, forat, firdaus, fil, kafur, kanz, maeda, al majus, marjan, mask, nuskha, harut and marut, wareda, wazir, yaqut.

In addition, many terms in Classical Arabic literature are transliterations or calques of the Persian: Khamsa Mustaraqa from Panjeh-ye Dozdideh, Mushahira from Mahianeh, Nisf an-Nahar from Nim-ruz, an-Namal al-fares from Murcheh-Savari, Maleeh (origin of Levantine Arabic mniih “good, well”) from Namakin, Beyt an-Nar from Ateshkadeh, Balut al-Moluk from Shah-balut, Samm al-Himar from Khar-zahreh, Lisan al-thawr from Gav-zaban, Reyhan al-Mulk from Shah-Esperam.

Sources:

Eilers, Wilhelm. Iranisches Lehngut im arabischen Lexikon: Über einige Berufsnamen und Titel. Gravenhage: Mouton, 1962.

Lane, Edward William. An Arabic-English Lexicon.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2002.02.0021%3Aroot%3Dxmn

Hovannisian, RIchard G.; Sabagh, Georges. The Persian Presence in the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Tafazzoli, A. Arabic Language ii. Iranian loanwords in Arabic.

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/arabic-ii.

Browne, Edward. A Literary History of Persia, Vol. I.

MacKenzie, D.N. A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary. Psychology Press, 1971.

Shir, Addi. Al-Alfâz Al-Fârsîyya Al-Mu`arraba (A Dictionary of Persian Words in the Arabic Language). Library of Lebanon, 1980.

Gharib, B. Sogdian Language i. Loanwords in Persian.

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sodgian-language-i-loanwords

Agius, Dionisius A. Classic Ships of Islam: From Mesopotamia to the Indian Ocean. Brill Academic Pub, 2007.

Cheung, Johnny. Etymological Dictionary of the Iranian Verb. Brill Academic Pub, 2007.

علي الثويني. التائه بين التأثيرات اللسانية و عقدة الخواجة 2-9/محمد مندلاوي

http://www.hekar.net/modules.php?name=News&file=print&sid=8603

تاثیر زبان فارسی بر زبان و ادبیات شبه قاره هند. محمد عجم.

http://www.hozehonari.com/PrintListItem.aspx?id=22896