Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. This narrative stems from a brief trip to Larestan, Iran during the Persian New Year (late March-early April) of 2014.

Roots in Larestan

My father is from Lārestān, a non-Persian-speaking, hybrid Sunni-Shi’a pocket tucked away in the southeastern-most portion of Fārs province in Iran (ancient Persis), just inland from the Persian Gulf. There, in the embraces of rolling foothills dotted with chamomile shrubs and tamarisk trees, he passed his childhood and adolescence, before moving to Shiraz to attend what was then the royal Pahlavi University; the premier university of early modern Iran. Today, Lar proper is a bustling regional center of over 50,000 souls, replete with luxury apartments, its own international airport, a multi-purpose sports stadium, foreign language schools and gated orchard communities. But his memories of Lar—which happens to be located atop the seismic fault lines of two tectonic plates—are as bitter as they are sweet. On April 24, 1960, a devastating earthquake struck Lar, reducing a large portion of the historic sun-baked brick and timber town to rubble, and claiming the lives of about 3,500 of its inhabitants (about a fourth of its population at the time). Following this tragedy, Lar’s inhabitants set out to construct a new settlement with government funding slightly north of the ruins, which they called Lār-e Jadīd or “New Lar”, while Lār-e Ghadīm “Old Lar” remained in a state of ruin but was gradually rebuilt and resettled by migrant workers from surrounding villages over the decades. At the time of writing, per my personal observation the two settlements are contiguous with each other.

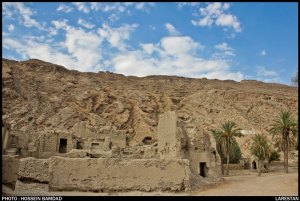

Ruins at Lār-e Ghadīm, or “Old Lar” (2014). An earthquake in 1960 reduced the historic town to rubble.

My father’s immediate family was dispersed for days following the 1960 earthquake, and it took hours of pursuit to retrieve all 14 of his siblings. For a time following 1960, informants report that Lar was reduced to a pile of rocks inhabited by a dwindling population living in abject misery. The tragedy left an imprint on his childhood and spawned within him a yearning for migration and higher education, first on the well-trodden path to Shiraz and finally to the United States. This article is a compilation of my observations from a brief journey through Lar, focusing on peculiarities in the culture and history of the region and Lari, a modern iteration of “Middle Persian” (inasmuch as it refers to the southern Middle Iranian vernaculars in Fārs province prior to the spread of Muslim New Persian from Khorāsān) and the language of my father’s boyhood.

Larestan (marked in red) consists of a series of settlements, the largest of which is Lar.

Lar: Jewish origins

Lar was probably originally a Jewish settlement, and one thing we know for certain is that it boasted a prosperous Jewish community as early as the 16th century. The French traveler Jean-Baptiste Thévenot reports that most of the inhabitants of Lar were Jewish silk farmers when he visited Larestan in 1687, and a Spaniard who visited the town earlier in 1607 met there a “messenger from Zion” named Judah. But as with other Persian Jewish communities (save the Georgian Jewish deportees employed as silk worm farmers in Māzanderān), the Jews of Lar suffered at the hands of the Safavid rulers during the 17th and early 18th centuries. Indeed, the pogroms and mass conversions are described by the Judeo-Persian chronicler Bābāi ibn Luṭf. According to him, the persecutions throughout Persia during the reign of Shāh Abbās I began some time before 1613 and originated in the city of Lar, whose rabbi had converted to Islam and taken the name Abul-Hasan Lāri. This renegade Lari rabbi secured a royal edict (farmān) whereby every Jew in Persia was required to wear a discriminatory badge and headgear. This in turn culminated in the abrupt expulsion of hundreds of Jews from the capital city, Isfahan, on account of their conspicuous newfound “impurity”.

Lar was nonetheless historically a center of Judeo-Persian literary activity, and among the notable scribes and translators was Judah of Lar in early 16th century. A Florentine traveler, Giambattista Vecchietti (1552–1619), even collected ancient Judeo-Persian manuscripts from Lar and brought them back to Europe. We know that a Jewish community existed in Lar through the beginning of the 20th century, and according to BM (1907, p. 51) there were 70 Jews living there in 1907. They were soon thereafter expelled from the city and walked all the way to the northern city of Jahrom, eventually settling in Shiraz and thence Palestine. Regrettably, there remain no traces of their synagogues or other socio-cultural spaces within Lar proper.

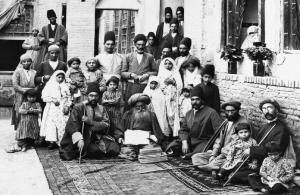

Persian Jews in Shiraz, early 20th century

The language spoken by Jews in Lar, historically known as “Judeo-Shirazi” (endonyms: Jūdī, Chodī), is a member of the Larestani branch of Iranian languages and was written using the Hebrew alphabet. It is closely related to modern Lari, and served as the medium for their literary productions. Perhaps it helped preserve the local dialect as distinct from New Persian for many centuries after the Islamization of Fārs. Unlike New Persian, which evolved from the Pārsig-Dari language of the Sassanian court at Seleucia-Ctesiphon, Larestani appears to be derived from various unattested Middle Persian dialects spoken by the Zoroastrian and Jewish inhabitants of Fārs province prior to the spread of New Persian. Modern Laris may have originally been a semi-nomadic Sunni pastoralist group with ancestors who had extended contact with the inhabitants of the Lur- and Kurdish-dominated highlands to the northwest of Fārs, and gradually displaced the Jews over several centuries (see discussion below). It is possible, based on historical reports, that many local Jews converted to Islam following a hypothetical trajectory of Muslim transhumance into the region.

Despite the absence of any material or linguistic evidence of a Jewish past within Lar proper, the non-Muslim heritage of Larestan remains at least nominally operative in the ethnic consciousness of modern Larestanis. One Lari informant mistakenly identified the region’s original inhabitants as Armenians (Christians)—indicating that a general awareness of Lar’s non-Muslim past remains ingrained in the social memory of the people, regardless of academic familiarity with the subject.

Ruins at Lār-e Ghadim, or “Old Lar.”

Arabic Bilingualism in Larestan

Because of its location on the caravan route connecting southern Iran to the Persian Gulf ports, Larestan has traditionally held an opportune position in trade with Arabic-speaking territories across the Persian Gulf. But throughout the medieval period Larestan was nearly always an obscure region, seldom becoming involved in the politics and conflicts of mainstream Persia. Most of the settlements within Larestan including Khür, Khonj, Gerāsh, Fishvar, Evaz, and Bastak are Sunni Muslim (اهل تسنن ahl-e tasannon), except for the city of Lar itself, which like the rest of Iran is majority Shi’a (اهل تشيع ahl-e tashayyo’). The Sunni inhabitants of Larestan maintain particularly close cultural and economic ties with their coreligionists across the Persian Gulf, and can be seen sporting conspicuously Qatari- and Emirati-style hijabs and garments in the central bazar of Lar proper. One entrepreneurial family has even opened a shawarma restaurant in Khür (c. 2014) that has recently blossomed into a gathering place for eager patrons hailing from far and wide in the region. As such, Gulf Arab fashions and tastes are flourishing in Lar, and there is a high degree of Arabic language proficiency.

The interior of an Emamzadeh in Lar, Iran (2014). Mirrorwork is a common feature of Iranian Islamic architecture.

Within my own extended family, Arabic proficiency is pervasive. Two uncles worked their careers in Kuwait and Abu Dhabi, and in particular are familiar with Iraqi and Gulf folk songs, including Meyhāna (ميحانة) and Bayn el-’asr wel Maghreb (بين العصر و المغرب). The performance of these songs together with my uncles, often accompanied by a tombak, served as a common form of entertainment at family gatherings.

Lari families have historically transplanted to Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE– where they are known collectively in Arabic as ‘ajāyem (عجايم; sing. ‘ajami عجمي). Laris have inhabited these countries for generations, usually maintaining their language and cuisine. Dubai’s oldest quarter, known as Al Bastakiya (البستكية), is namesake to the enterprising textile and pearl traders from Bastak, Larestan who settled and developed the area. My own family has relatives in Bahrain as well as a large branch situated in Qatar, descended from an aunt who married a Lari-Qatari sheikh and bore him eight children about half a century ago.

Al-Bastakiya is Dubai’s most historic quarter. Established at the end of the 19th century by affluent textile and pearl traders from Bastak, Larestan, its labyrinthine adobe lanes are lined with restored merchant’s houses, art galleries, cafés, and boutique hotels. Pictured here are two prominent bādgirs (بادگير), or “windcatchers”– a quintessentially Iranian architectural form encountered in Lari colonies throughout the Persian Gulf region.

Men from Lar have a long history as merchants engaged in Indian Ocean maritime trade and in local overland trading between the Persian Gulf and inland Iran. Laris assumed a new role in the trade of the Persian Gulf region with the beginning of oil production in Kuwait and other small states after World War II. At that time, Lari men like my uncles began migrating to Kuwait to open small shops that catered to the huge influx of migrants working in the oil industry and in construction. Typically, Lari men left their families and worked in Kuwait for periods of 18 months to several years before returning home for six month visits.

The Friday Mosque, Lar, Iran (2014)

In contrast to the educated migrants from Egypt and Palestine who staffed the Kuwaiti bureaucracy, and the uneducated migrants from Arab countries, Pakistan and Asia who worked as unskilled laborers, almost all Laris were engaged in retail trade. Typically a man would start out in business with a small shop in partnership with another man, often a relative. The stores ranged from green groceries to import shops. Remittances also raised the standard of living for most Lar families allowing them to buy a variety of consumer goods. In fact, the smuggling of such articles as Japanese TV sets, wrist watches and tape recorders was a lucrative side business for many migrants. Following the betterment of the economic situation in Iran in the 80’s, the tradition of Lari labor export to Kuwait declined significantly and finally ended. Today, Laris look closer across the Gulf–to the Emirates and Qatar, for exporting labor and investments.

Larestani Cuisine

Larestani people’s diet consists of a mixture of traditional Persian foods, as well as local dishes and those from surrounding coastal regions on the Persian Gulf. A few representative local dishes are described below:

-Kabāb Kenje-ye Lāri: a traditional dish consisting of young lamb marinated in strained yogurt, onion, black pepper and salt for several days, skewered and barbecued over an open flame.

-Polo malakh: Small shrimp (malakh) cooked with mung beans, saffron, salt, and black pepper served with pomegranate molasses sauce as a condiment.

-Breads: A variety of breads are made from unsifted wheat flour, including ninanü, botonür, bālatova, jarādak, which are cooked quickly on a griddle. These breads are seasoned with ma’va– the local favorite seasoning consisting of ground mustard seeds, dried ground māhi-e motü (a local anchovy variety imported from the Persian Gulf coast), and salt which is fermented together under direct sunlight over 3-4 months. This base is often accompanied by bābüna (chamomile) and konjed (sesame seeds). Other traditional breads include taftu (the dough consists of unsifted wheat flour, sunflower oil, whole milk, baking soda, salt; topped with sesame and golrang, a local herbal food coloring resembling saffron, and baked in a ceramic tannur oven), taptapi, gapok and non-e nāzok.

-Tokhm o dol and tokhm o kher: eggs seasoned with turmeric, salt, black pepper and tossed with a variety of local mushrooms gathered from surrounding mountains (two varieties: dol and kher)

-Khoresht-e khoraü: a local leafy green (khoraü) stewed with lamb, potato, and onion and seasoned with turmeric, salt and pepper served with rice.

Kabāb Kenje-ye Lāri served with traditional taptapü bread and fresh Persian basil. Photo taken at the author’s family orchard outside of Lar, 2014.

Comparison with Sorani Kurdish and Persian

Larestani is an Indo-European language belonging to the southwestern subgroup of the Iranian branch, and is spoken by about ~150,000 people in Iran and abroad. Like Persian, Larestani is Indo-European in its core vocabulary, however it also features an albeit small number of loans from non-Indo-European languages in its general vocabulary, particularly Classical Arabic (via Persian) and Gulf Arabic (via bilingualism). Other languages in the southwestern subgroup of the Iranian branch include Modern Persian and all of its ancestors and sisters, Luri, Kuhmareyi, and the Kumzari language of northern Oman. As discussed above, the Larestani languages are direct descendants of unattested Middle Persian vernaculars that survived the spread of Muslim “New Persian” from the Khorāsān and Central Asia. All of the Larestani languages and dialects together form a single speech community, despite considerable lexical and morphological variation. For example, whereas Khüri has ēkā “here”, in Lar proper the same word is heard as enke, but these variations are within the bounds of mutual intelligibility to native speakers. Kurdish languages belong to the Northwestern subgroup of Iranian, but there are a number of analogous lexical and morphological paradigms in Kurdish and Larestani that are worthy of noting. I attribute these similarities to areal features, whence the ancestral Proto-Larestani and Proto-Kuhmareyi languages must have been in contact with ancestral Kurdish languages at some point in their development following the Old Iranian stage (Kuhmareyi even features a definite marker –aku, reminiscent of Kurdish -aka):

| English | Larestani (Lar) | Kurdish (Erbil) | Literary Persian |

| “son” | pos | kurr | pesar |

| “daughter” | dot | kich | dokhtar |

| “mother” | nänä | dayk | mādar |

| “brother, sister” | berosü, khongü | bra, khweshk | barādar, khwāhar |

| “I went” | chedem | chūm | raftam |

| “he said he cannot go today” | oshgot ērōz oshnáshā ochü | wuti amrro nátwane biche | goft emruz nemitavānad beravad |

| “where are you going?” | äko ächedoish? | akwe dachi? | kojā dāri miravi? |

| “they said [to me]” | [mava] shogot | [pem] wūtiyan | [be man] goftand |

| “may it be” | bü | bet | bāshad |

| “beautiful” | ju | jwan | zibā, ghashang, khoshgel |

| “big, large” | got, gapü | gawre | bozorg |

| “mouth” | käp | dam | dahan |

| “leg” | leng | laq | pā |

| “in” | tek | tēy…(da) | tū |

| “alone” | sevā | tanyá | tanhā |

| “he/she comes” | dā | det | miāyad |

| “he/she had come” | undesse | hátibū | āmade būd |

| “yesterday” | de | dwene | dirūz |

| “tomorrow” | säbā | sbayne | fardā |

| “I want; I don’t want; I wanted; I didn’t want” | mävi, omnóvi; mäves, omnáves | amawe, námawe; wistim, namwist | mikhwāham, nemikhwāham; khwāstam, nakhwāstam |

| “you slept” | khätesh | khawit | khābidi |

| “I ate” | omkhä | khwardim | khordam |

| “they fall” | äkeven | dakawin | miyoftand |

Larestani and Kurdish have together retained a number of phonemic archaisms from the Middle Iranian stage that have disappeared in modern Persian. For example, Lari and Kurdish have a rounded front vowel at the beginning of the word “we” (Lari: amā, Kurdish: emā), while modern Persian has mā. Rounded long vowels –ō, –ē from Middle Iranian are preserved in Larestani (Lari: gōsh vs. Persian: gūsh “ear”) and Kurdish (Kurdish: rōj, Lari: rōz, Persian: rūz “day”) except for in modern Persian borrowings, which are assimilated (Lari güshi “telephone”). Lexical archaisms are numerous and include Lari gapü “big” and got (from Proto-Indo-European *gʰrewd-, *gʰer-, cognate to English great, Latin grandis, Albanian ngre), whereas Old Persian adopted a Median word, now pronounced bozorg (from Proto-Indo-European*weǵ- Old English: wacan, wacian; English: wake. Originally meaning “endowed with generative power”, from Old Persian vazra- via palatilization and sibiliation, already literary Old Persian vazarka, Middle Persian wuzurg).

Larestani and Kurdish both share a postposed directional complement à “to”, and in Lārestāni a derivative o- is used to express general possession, “to have”, when complemented with a pronomial enclitic (note immediate possession in Lārestāni parallel to Arabic is expressed using pronomial clitic + bā; i.e. ma qalam omnebā “I don’t have a pen [with me right now]”). Kurdish uses a possessive pronoun + haya/niya. Larestani: chedem à madrasa, Sorani Kurdish: chūm à madrasa “I went to school”. Persian does not use a directional complement.

| English | Larestani |

| “I have, I don’t have” | ome, omnísi |

| “You have, you don’t have” | ote, otnísi |

| “S/he has, s/he doesn’t have” | oshe, oshnísi |

| “We have, we don’t have” | mo’e, monísi |

| “You (pl.) have, you (pl.) don’t have” | to’e, tonísi |

| “They have, they don’t have” | sho’e, shonísi |

The dative construction takes two forms in Larestani: one is the postponed directional complement attached to both nouns and pronouns discussed above (Larestani: à ma = “to me’), and the second is a more conservative dative construction that takes the form of a postpositional suffix -va attached to the pronoun it modifies. The latter is highly unusual in the southwestern Iranian group, which includes Persian, although postpositions are found in Caspian languages. The construction is notably parallel to Oghuz Turkic –(y)a/-(y)e, and is encountered elsewhere in northern Tajik Persian dialects, where it developed under the influence of eastern Turkic (Tajik -ba > Uzbek -ga “to”). Perhaps Larestani obtained this exclusively pronomial dative construction from the neighboring Qashqai Turkic, but there is no evidence of widespread bilingualism or substrate as in the case of northern Tajik to explain an eccentric morphological innovation of this kind. Instead, it is likely a vestige of the Middle Iranian stage, inasmuch as a multitude of shared features between Larestani and peripheral Iranian languages are the likely heirlooms of an ancestral dialect continuum that connected genetically distant cousins (for example, lexical and morphological parallels between Larestani and Talyshi).

| English | Larestani | Qashqai (Turkic) |

| “To me” | mävä | mana |

| “To you” | tävä | sana |

| “To him/her” | shävä | ona |

Larestani verb inflection is strikingly different from Persian, her Southwestern Iranian-branch sister. The issue of ergativity in Larestani is discussed below. Three features set the Persian and Lari dialect groups in Fars province squarely apart from each other: (1) the ending of the second-person singular, Fars dialects –ē/-ī, Larestan dialects –eš; (2) the imperfective marker, Fars dialects mē-/mī-, Larestan dialects a(t)-; (3) the existence in the Larestan dialects of a present progressive by means of a locative construction based on the verbal noun. Moreover, the particular way of regularizing verb stem formation in the Larestan dialects may suggest input from a non-Iranian system. The pronomial clitics of Larestani past tense transitive verbs are placed in different positions from those of Persian, with a resemblance to the ergative construction of Kurdish. In addition, Larestani has a split proclitic-mesoclitic system of verbal negation: sho’äshā “they can”→ shonāshā “they cannot” but dā “S/he comes”→ nedā “S/he does not come”, while Persian has only proclitic: mitavānand; nemitavānand “they can; they cannot.”; as does Kurdish: datwanin; nátwanin “they can; they cannot.”

A complete conjugation of the intransitive verb čeda “to go” is provided below:

| infinitive | če-da ‘to go’ | |||||||

| stem | present | č | ||||||

| past | čed | |||||||

| participle | present | Not used | ||||||

| past | čedé | |||||||

| singular | plural | |||||||

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||

| indicative | present (imperfect) | a-č-ém | a-č-éš | a-č-ü | a-č-ám | a-č-i | a-č-én | |

| present progressive | a-čed-ấ-em | a-čed-ấ-eš | a-čed-ó-i | a-čed-ấ-am | a-čed-ó-i | a-čed-ấ-en | ||

| present perfect | č-éss-em | č-éss-eš | č-éss-e | č-éss-am | č-éss-i | č-éss-en | ||

| past | čed-ém | čed-éš | č-u | čed-ám | čed-í | čéd-én | ||

| past (imperfect) | a-čed-ém | a-čed-éš | a-č-u | a-čed-ám | a-čed-í | a-čed-én | ||

| pluperfect | č-ésson-em | č-ésson-eš | č-ésson-∅ | č-ésson-am | č-ésson-i | č-ésson-en | ||

| subjunctive | present | o-č-ém | o-č-éš | o-č-ü | o-č-am | o-č-i | o-č-en | |

| past | č-ez bem | č-ez beš | č-ez bü | č-ez bam | č-ez bi | č-ez ben | ||

| imperative | o-č-o | o-č-i | ||||||

In Kurdish, the simple past tense of transitive verbs is formed from the past stem of the verb and an agent affix—the ergative construction. Modern Larestani languages, alongside Kurdish, display split-ergativity. Ergative alignment is used in the past tense (present perfect, preterite, past imperfect, pluperfect and past subjunctive) of transitive verbs and some intransitive verbs (e.g. omgot “I said”, otnāshā “You cannot”; but khätem “I slept“, nāfämesh “You do not understand”). The former two constructions have intransitive ergative character, but the latter two illustrate the fact that Larestani also features nominative/accusative morphology. Ergativity is thus more pervasive in Larestani than Kurdish. Persian is a non-ergative language.

| English | Larestani (Lar) | Kurdish (Sorani) | Literary Persian |

| “I want; I don’t want” | mä-vi → om-nó-vi | damawe → -m nawe | mikhwāham, nemikhwāham |

| “You said you don’t have money” | ot-got pül ot-ne-bā | wuti parat niya | gofti pul nadāri |

| “We bought” | mose | krriman → -man krri | kharidim |

| “I gave you water” | Mä aw’m à to dā | Minit pe awem da | Man be to āb dādam |

Sorani Kurdish has (d)a- as a habitual and progressive verbal prefix, while Larestani has the habitual prefix a- and a- + past stem + a medial affix –ā- for the present progressive construction:

| English | Larestani (Lar) | Kurdish (Sorani) | Literary Persian |

| “I am going” | ächedāem | dachim | dāram miravam |

| “you are seeing (witnessing)” | ädedāesh | dabini | dāri mibini |

| “S/he is doing” | äkerdoy | dakat | mikonad |

Entrance to the author’s uncle’s orchard (bāgh) located southwest of Lar city, where families retreat for feasts, gardening and recreation.

The Future of Lari

No two people speak the same language exactly alike. As such, languages may evolve insularly among speakers of the same language in the general absence of external pressures (for example, Icelandic). But language change is not random—it flows in the direction of accents and phrases admired and emulated by large numbers of people. Once a target accent is selected, the structure of the sound changes that move a speaker away from his or her own mode of speech is governed by rules. Sound changes follow unspoken and unconscious rules – the sound changes are not idiosyncratic or confined to certain words; rather, they spread systematically to all similar sounds in the language.

Lari is not an exception to this rule. As an oral language, Lari literature is scant and limited exclusively to poetry. Without a standardized, pervasive literary form or a compendium of Lari literature, the language is particularly volatile to assimilative pressures. The various dialects are considerably different from each other and seem to be distinguished primally upon village and secondarily upon Sunni-Shi’a sect affiliation. The language of school education is Persian, and all educated Larestanis speak Persian as their second language. Persian has also become the language of interethnic communication, particularly between Laris and the Turkic Qashqai element in Larestan. Many Larestanis with ties to the Gulf (mainly Sunnis from Khür, Gerash, Bastak, and Evaz) speak Arabic as a second or third language. As such, the Shi’a Lari dialect has been Persianized in its lexicon and phonology and the Sunni dialects have been Arabicized—processes that have accelerated in the past several decades and the former may ultimately lead to endangerment.

I will only deal with lexical assimilation with Persian, as phonological assimilation is outside the scope of this article. Of note, I was surprised to behold an episode of lexical transformation between my father and his siblings. My father, having left Larestan over 40 years ago, speaks a vernacular true to the spoken language of that era, while those who have remained within Larestan have been subjected to assimilation pressures as a result of improved school education and communications with the rest of Iran, as well as increased migrant traffic in both directions. As such, my father’s vernacular features lexical archaisms that have since been rendered obsolete in favor of Persian borrowings in the current Lari vernacular.

| English | Lar (pre-1975) | Lar (2014) | Persian |

| “A little, a bit” | chondokü | kami, ye zara | kami, ye zare |

| “yawn” | käpfroghü | khamyāza | khamyāze |

| “I speak” | kwät äderem | harf azanem | harf mizanam |

| “a local pancake made from oil, wheat flour, egg, chamomile flower, local greens” | ninanü | ninani, regāk (from Arabic) | — |

The future of Lari seems bleak, as generation Y has effectively ceased to employ Lari, even as a mode of family communication. As such, Lari is to be classified as unstable, for the sphere of its use is steadily diminishing. Socio-cultural stigmatization of Larestan by inhabitants of Iran’s major urban centers compounded by new and improved contacts with the rest of Iran via Persian language television and radio broadcast have inspired generation Y to emulate Tehrani Persian speech, even in response to their parents speaking in Lari. Moreover, knowledge of and proficiency in Persian is associated with upward social mobility, which in turn has influenced the older generations to incorporate Persian words and phrases into their speech. Of note, one can hear the Persianized khūbesh? instead of Lari khäshesh? (“Are you well?”)– a form that had no currency fifty years ago but is now canonical if not preferred.

Sources

Anthony, David W. “The Horse, The Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World.” Princeton Review Press: 2007.

Bonine, Michael E.; Nikki R. Keddi. Modern Iranian Dialectics.

Fischel, Walter Joseph; Netzer, Amnon. “Lar.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. 2008 The Gale Group. All Rights Reserved.

Loeb, Laurence D. Outcaste (RLE Iran D): Jewish Life in Southern Iran.

McIntire, Emily Wells. “From Lar to Kuwait.” The Search for Work. Cultural Survival Inc., issue 7.4 (Winter 1983).

Thank you for this article. I have been researching my own family history and turns out my father’s side is from Larestan. Both my grandparents moved to Kuwait from Larestan many years ago. Hopefully I can visit Larestan one day 🙂

Hi I am also a Larestani.

What do you mean by Non-Persian speakers?

I have you know that our language is a dialect of Parsig, (middle Persian), yes it is similar to Kurdish and Lori.

The language of ancient Persians and Medes (forefathers of the Kurds and Azaris) were the same but had different dialects.

We are the real Persian speakers and proud of it. Dari-Farsi (the official language of Iran) has never been the language of Persians. In fact Persian and Azari poets never call Dari Persian.

Over the past 400 years many areas of greater Fars became Dari-Farsi speakers. Today greater Larestan (north west Hormozgan and southern Fars).

Apart from Larestan, Dosiran in Kazeroon county, Kohmareh north of Shiraz, and Khollar and Sepidan in north east FArs, speak a dialect of our language. This shows that all the Persians had this language (Parsig or Larestani or middle Persian) as their mother tongue.

Dari-Farsi is a language developed after Islam and has it’s roots in the east of Iran.

Arabic has never been the language of commerce in our region. Those Grashi, LAri BAstaki and Avazis and many more from Bolouk and Sfharafou that migrated to Bahrain, Kuwait and the UAE have had to learn Arabic to trade with the native Arabs of those places. I know people who are in their 90s and haved lived in Bahrain for 70 years, but have difficulty speaking Arabic.

You have also put too much emphasis on the Shia Sunni thing, Larestanis don’t care about each others religion, I personally have from my father’s side Gabri or Zorostrian herritage, and from my Great grand mother Chodi (Persian-Jewish) heritage.

Please take good care when you are writing on Larestan and the regions ancient language.

Dorood bar shoma, I would like to contact you via email if you may kindly allow me.

My email is maa1441@gmail.com

Pingback: Hidden in Plain Sight: Illuminating Indo-European Words in Persian – borderlessblogger