Written by Afsheen Sharifzadeh, a graduate of Tufts University focusing on Iran and the Caucasus. The present article aims to familiarize with the reader with the past and present of Iranian Azerbaijan, the Iranian “Old Azari” and Turkic Azeri languages. Salient features of modern Azerbaijani Turkic are outlined herein, particularly vis-à-vis Anatolian Turkish.

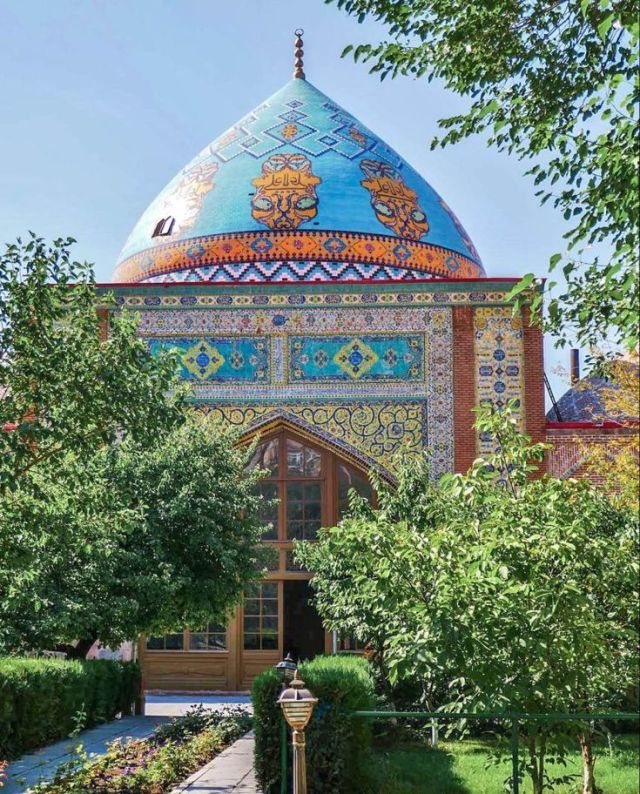

The Persian “Blue Mosque” in Yerevan, Armenia (c. 1765 A.D.), a unique example of Persian mosque architecture, was commissioned by the Afshārid scion Husayn ‘ali Khān, the Khan of Erivan (خانات ايروان Xānāt-e Iravān; Երևանի խանություն Yerevani khanut’yun) when the local Shia population consisted of a Persian elite and a Turkic semi-nomadic military class. The outer shell of the cupola is decorated with a field of turquoise-glazed bricks and various bands of colorful geometric patterns, above which lie eight uniform medallions resembling the head of a predatory feline.

Background

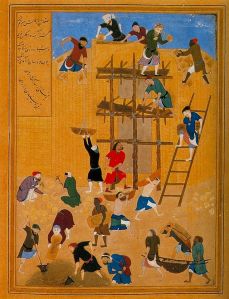

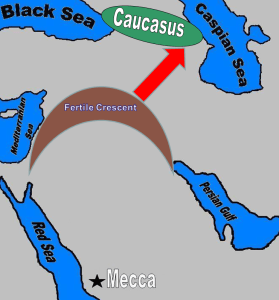

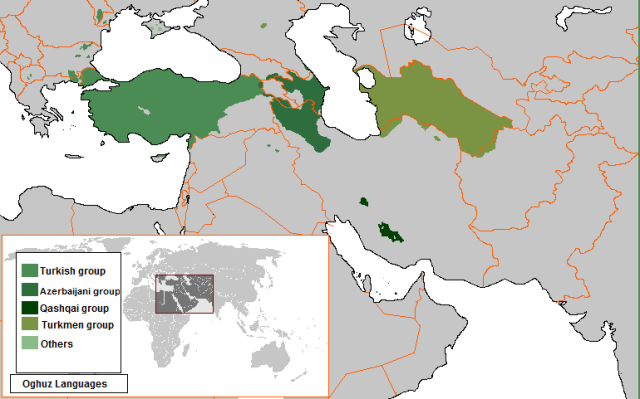

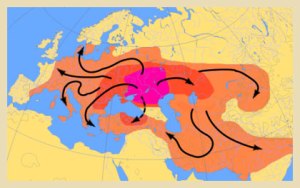

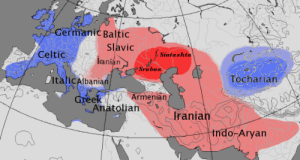

Azerbaijani is a member of the Oghuz branch of the Turkic family, and thus shares that clade with modern Turkish, Turkmen, Gagauz, Qashqai, Salar, Khorasani Turkic and Khorezmian Uzbek. It was brought to its present homeland by a broad wave of invaders from Central Asia who “flooded Khorāsān” and thence Iran and Anatolia when “Tūrān defeated Ērān” in the 11th century A.D. The aftermath of the Turko-Mongol incursion resulted in the birth of the Great Seljuk Empire (آل سلجوق Āl-e Saljūq; c. 1037-1194 A.D.), founded by a dynasty of Oghuz Turkic provenance that became sedentarized and adopted Persian language, culture, and tradition, and later exported this Turko-Persian culture to Anatolia.

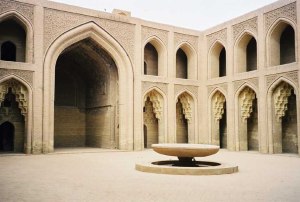

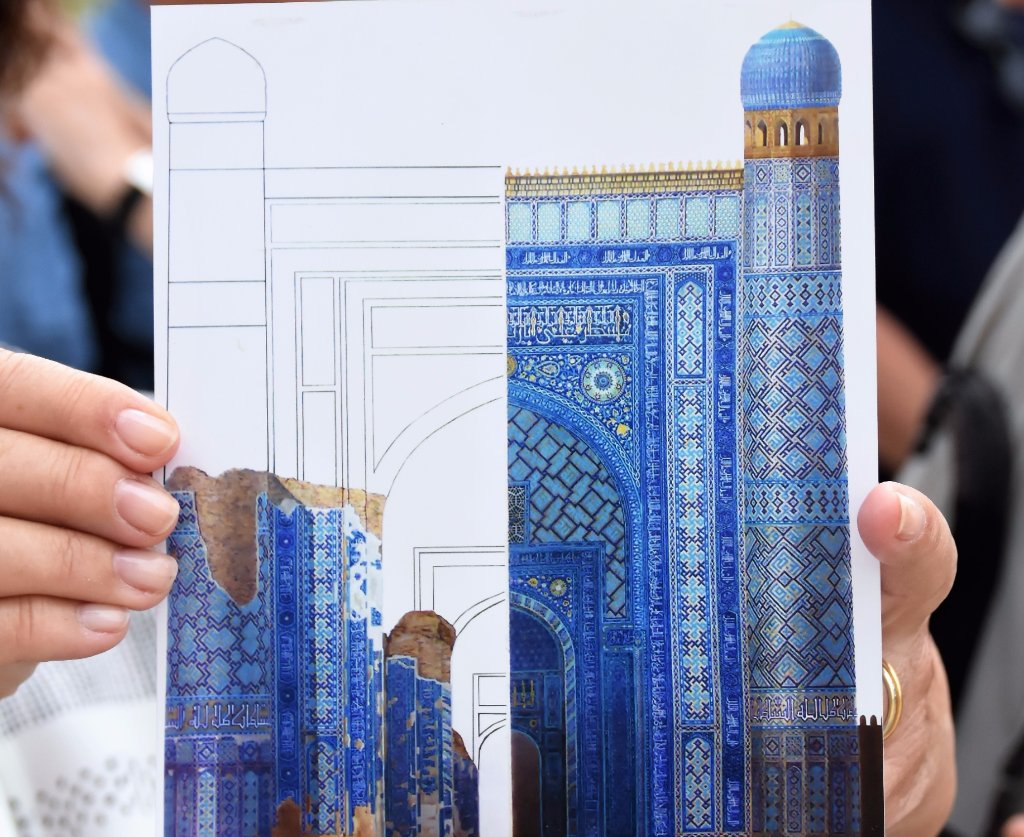

(A) Painting of the iconic Persian “Blue Mosque” of Tabriz (مسجد كبود masjed-e kabūd) in ruins, by a French tourist, Jules Laurens, c. 1872; (B, C&D) The current state of the Blue Mosque with remnants of its elegant cobalt blue Persian tilework. The structure was commissioned by Jahān Shāh, the ruler of the Kara Qoyunlū in 1465 A.D. It was severely damaged in an earthquake in 1780 A.D., with moderate but incomplete restoration efforts beginning in the 1970s.

(A) Painting of the iconic Persian “Blue Mosque” of Tabriz (مسجد كبود masjed-e kabūd) in ruins, by a French tourist, Jules Laurens, c. 1872; (B, C&D) The current state of the Blue Mosque with remnants of its elegant cobalt blue Persian tilework. The structure was commissioned by Jahān Shāh, the ruler of the Kara Qoyunlū in 1465 A.D. It was severely damaged in an earthquake in 1780 A.D., with moderate but incomplete restoration efforts beginning in the 1970s.

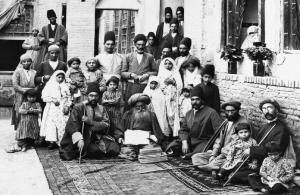

Much as in the case of Khwarezm, a minority Turkophone military class emerged over the course of centuries in the context of a sizeable Iranian peasantry within the ancient Iranian Zoroastrian province of Ātṛpātakāna (from the Old Persian name Ātṛpat, “protected by fire”; an Achaemenid satrap who founded the independent kingdom of his namesake + suffix –akāna; whence MP ܐܕܪܒܐܕܓܐܢ Ādurbādgān → NP آذربايجان Āðarbāyjān “Land of the Holy Fire”). In the centuries thereafter, the autochthonous Iranian idiom of Azerbaijan, the so-called “Old Azari” language, faced a gradual decline. Under this new dynamic, militaristic Oghuz clans in Azerbaijan rose to the highest echelons of regional power following the collapse of the Mongol Ilkhanid state (ایلخانان Ilxānān; Hu’legiīn Ulus) with the rise of the Kara Qoyunlū and Āq Qoyunlū Turkmen at the end of the 14th century A.D. It was only in this period that Old Azari began to lose ground at a faster pace than previous centuries, however it was definitively supplanted by Turkic no earlier than the Safavid period (دودمان صفوى Dūdmān-e Ṣafavī; c. 1501-1722 A.D.). Turkophones did, however, adopt the former Iranian people’s endonym, آذرى Āðarī. Later the Turkophone Azeri nucleus gave rise to the Safavid (originally an Iranian-speaking clan that became Turkified and adopted Turkish as their vernacular under the Āq Qoyunlū, as evidenced by the Old Azari-language quatrains of Shaikh Ṣafī-al-dīn, their eponymous ancestor, and by his biography), Afshārid and Qājār dynasties, although their courts remained discriminantly Persian in their official language and culture.

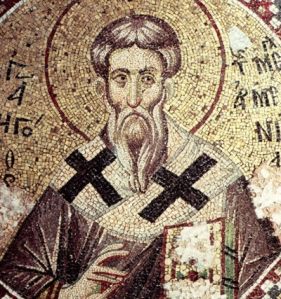

(left) Shaikh Ṣafī ad-Dīn Isḥāq Ardebīlī (1252-1334; شيخ صفى الدين اسحاق اردبيلى ); the eponymous ancestors of the Safavid Dynasty, composed important verses in Classical Persian and the contemporaneous Tāti language Ardebīl, a dialect of the Iranian “Old Azari” language. His descendants, backed by powerful regional soldiery of Turkic stock, later adopted Turkic as their vernacular. He is interred in an elaborate tomb complex in Ardebīl (right).

On the Old Azari Language and the recent Turkification of Azerbaijan

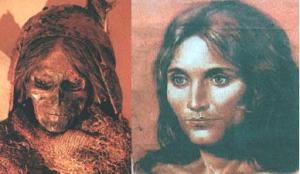

The “Old Azari” language–previously one of the major Iranian languages–comprised a sprachbund of dialects distributed in a broad range between lake Urmia in the west and the Caspian littoral in the east. Old Azari seems to have shared a genetic affinity with the ancestor of the modern Talysh language, and it further appears to form a broader group with the so-called “Northwestern” branch of Iranian including modern Gilaki, Māzanderāni, Semnāni, and Zaza-Gorani. Some linguists hold that the southern Tāti varieties of Iranian Azerbaijan around Tākestān, as well as those of Harzand and Karangān, among other modern dialects sprinkled throughout Northwestern Iran, are peripheral remnants of Old Azari. As such, this language has been spoken in the region of Azerbaijan for at least three millennia.

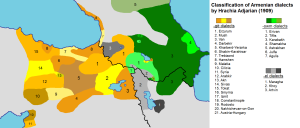

The modern distribution of Tāti language and its close relative, Talysh (Tāleshi), in Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. These two languages likely represent the last exponents of a variety of the ancient Median language, which has been used in Azerbaijan for nearly three millennia.

As the available compendia which first make mention of the idiom appear only in the centuries following the Islamic conquest of Azerbaijan, the Old Iranian stage of the language remains unknown. However on the basis of shared sound changes and the absence of evidence for a significant population dislocation event, Yarshater posits that Old Azari [and its daughters in Tāti] must inevitably be descendants of the ancient Median language (note: despite recently-popularized folk belief, the “Kurdish” languages are demonstrably not so. They instead appear to be part of a group with Central and Southwest Iranian dialects, layered over a Northwestern Iranian substratum following their migration into the territory of ancient Media).

The first sources which make mention of the language date to the early Islamic period (Ibn al-Moqaffa, 759 A.D.), and suggest the language of Azerbaijan, Fahlawī (الفهلوية al-fahlawīya), formed a group with the vernaculars of Ray, Hamadān, and Isfahān. Later an anecdote concerning Abū Zakarīyā Kāteb Tabrīzī and his teacher Abu’l-ʿAlāʾ Maʿarrī refers again to the vernacular of Azerbaijan in the 12th century A.D. While Kāteb Tabrīzī was in Maʿarrat al-Noʿmān in Syria, he met a fellow-countryman and conversed with him in a language which Abu’l-ʿAlāʾ could not understand. When Abu’l-ʿAlāʾ asked him to identify the language, Kāteb told him it was “the language of the people of Azerbaijan.” The statement of Yāqūt in the 13th century in his Moʿjam al-boldān to the effect that “The people of Azerbaijan have a language which they call al-āḏarīya (الآذرية), and it is intelligible only to themselves” makes it clear that Old Azari was still current in Azerbaijan on the eve of the Mongol invasion.

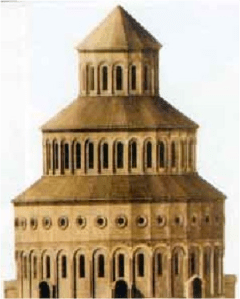

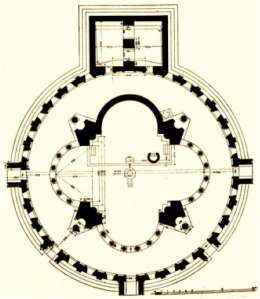

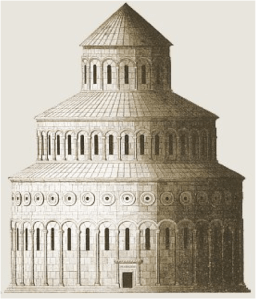

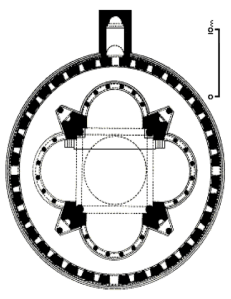

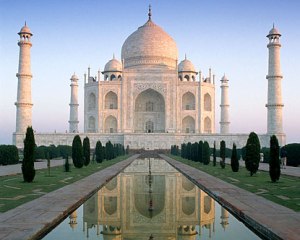

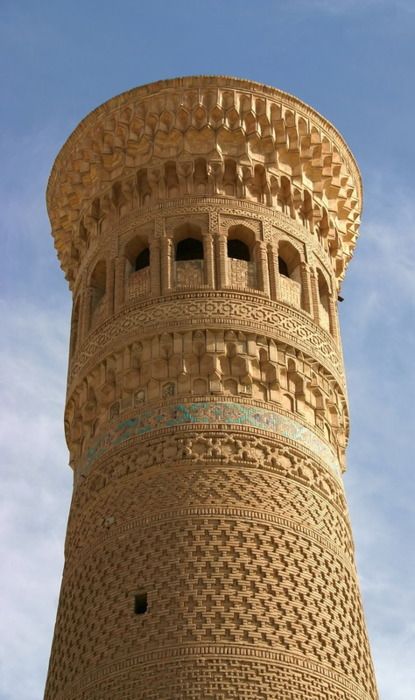

Remains of the Mausoleum of the Mongol ruler Il-khan Öljeitü, at Soltāniyeh, Zanjān province, Iran. In addition to its renown for carving and ornamentation, it is one of the largest brick domes in the world, just at the theoretical engineering limit for a brick dome and the third largest dome in the world after the domes of Florence Cathedral and Hagia Sophia. This structure was iconic in the repertoire of Persian architecture, and later inspired the Persian-style Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasavi and the Taj Mahal at Agra.

Remains of the Mausoleum of the Mongol ruler Il-khan Öljeitü, at Soltāniyeh, Zanjān province, Iran. In addition to its renown for carving and ornamentation, it is one of the largest brick domes in the world, just at the theoretical engineering limit for a brick dome and the third largest dome in the world after the domes of Florence Cathedral and Hagia Sophia. This structure was iconic in the repertoire of Persian architecture, and later inspired the Persian-style Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasavi and the Taj Mahal at Agra.

It is important to note that Old Azari retained its currency as the dominant vernacular of Azerbaijan for several centuries following the initial Turkic migration into the region in the 11th century A.D. Writing in the 14th century, Abaqa Ḥamdallāh Mostawfī attests to the enduring Iranian character of Azerbaijan’s urban centers, stating that Marāḡa and Zanjān spoke “modified” and “pure Pahlavi”, respectively (پهلوى مغير pahlavī-e moḡayyar and پهلوى راست pahlavī-e rāst; an undoubtedly imprecise reference to the Iranic Azari language in contrast to Turkic). It appears that Ardebīl’s language was previously one of the more important dialects of Old Azari, with Shaikh Ṣafī-al-dīn, the eponymous ancestor of the Safavid dynasty, composing dozens of dobaytīs (distichs) in its language. According to the account of Jean During, a contemporary French traveler, the inhabitants of Tabriz did not speak Turkish in the 15th century.

It appears Old Azari only lost its status as the majority language between the 16th-17th centuries with the ascent of the Qizilbash-backed Safavids. The subsequent influx of numerous Turkic military elements into the region further spread Turkic at the detriment of Old Azari, which in turn receded and ceased to be used, at least in the major urban centers. Notwithstanding the city of Tabriz maintained a number of distinctly Old Azari-speaking neighborhoods well into the Safavid period with the poet Ruhi Anārjānī composing a compendium of the language as late as the 17th century. However by the turn of the 20th century the Turkification of Azerbaijan was near completion, with the old Iranic speakers found exclusively in remote recesses of the mountains or other isolated areas such as Harzand village in Marand. Lamentably, language shift is currently in progress and the remaining Tāti dialects face a state of attrition and imminent endangerment.

|

English |

Old Azari (Ardebīlī; the language of Shaikh Ṣafī-al-dīn’s dobaytis, 14th c. AD) | Classical Persian |

Azerbaijani Turkish |

|

“life” |

ژير žir |

زيست zīst |

həyat |

|

“S/he was” |

برى |

بود būd |

idi |

|

“I went” |

شرم |

رفتم |

getdim |

| “soul” |

گون |

جان |

jan |

|

“My” |

چمن |

— |

mənim |

|

“S/he knows” |

زونر zūnar |

ميداند mīdānad |

bilir |

Azerbaijani Turkish in the 21st Century

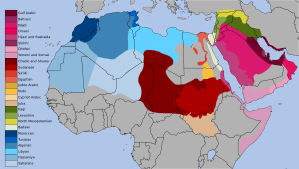

Today, Azerbaijani is a pluricentric language and exhibits a primary division in dialect: North [or Soviet] Azeri vs. South [or Iranian] Azeri. Prior to the political events which gave rise to the current dicentrism, the language was written exclusively in the Perso-Arabic script. Following the Treaty of Gulistan and therein imperial Russia’s acquisition of modern-day Azerbaijan from Qajar Iran, the northern variety became subject to widespread Russian influence and later a series of orthographic reforms under the Soviet regime. With the fall of the U.S.S.R., the new Republic of Azerbaijan adopted a modified Latin script in 1991. On the other hand, Iranian Azeri (self designated آذرى ديلى Azeri dili or ترک ديلى türk dili; Persian: تركى tōrkī), whose dialects compose roughly 15 million speakers or the majority of the Azeri-speaking community, persisted independently from its congener under the strong influence of Persian and, as in the past, is written in a modified Perso-Arabic script. Without any official status, Southern Azeri lacks a standardized form but relies strongly on the Northern variety for official media and broadcast.

The modern distribution of the Oghuz branch of Turkic (not depicted: Khorasani Turkic, Salar, Xorezmian Uzbek). Azerbaijani is genetically closest to Khorasani Turkic and Qashqai, although the northern variety has been strongly influenced by Turkish.

The Northern and Southern varieties of Azerbaijani are moderately mutually intelligible without training. Since, for several decades, there has been little, if any, cultural exchange between the two parts of Azerbaijan, the mutual intelligibility is decreasing. Today the two languages are remarkably distinct in phonology, morphology, syntax, and source of loanwords; purist efforts upon the Northern variety have uprooted numerous Persianisms in favor of Russianisms and revisionist Turkic models, while the Southern variety continues to rely upon Persian much as it has since its arrival to the region. By comparison, Anatolian Turkish has instead drawn from French and English.

| English | Turkish (Istanbul) | Northern (Soviet) Azeri | Southern (Iranian) Azeri |

| “To take” | götürmek | götürmək | آپارماخ aparmax |

| “To do; we do” | etmek, ediyoruz | etmək, edirik | الماخ، اليروخ eləmax, elirux |

| “what” | ne | nə | نمنه nəmənə |

| “university” | üniversite | universitet | دانشگاه danıšgah |

| “I caused him/her to read the book” | Ben Ali’ye kitabı okuttum | Mən Əliyə kitabı oxutdum | من عليه باعث الدوم كه كتابى اخودو Mən Äliyä ba’es oldum če kitabı oxudu |

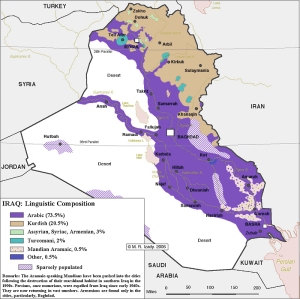

Southern Azeri dialects in Iran are varied, but all are mutually intelligible. The traditional centers of the language are Tabriz, Urmia, Ardebil, and Zanjān. In these areas, Azerbaijani is the language of the domestic, public and cultural spheres, while Persian enjoys superiority as it remains the language of education, literature, media and administration. Tehran has emerged in recent years as a new hub for the Iranian Azeri population, where the Azeri language is heard profusely throughout the city. It would seem that the Assyrian and Armenian Christian communities of Azerbaijan are functionally trilingual in their own language, Persian and at least passively Azerbaijani. Note a dialect of South Azeri is also spoken in the province of Kirkuk, Iraq.

Phonology

Southern Azeri vernacular is markedly distinct from its Soviet congener in phonology. The formal register of the language used in limited news and broadcast media relies on Standard [Northern] Azerbaijani phonology, however the vernacular language exhibits a number of eccentric features detailed here.

Non-initial syllables have vowel harmony, as in Turkish; many dialects, however, show signs of a dissolution of the vowel harmony (e.g., gəl-max– “to come” instead of gəl-mək). This process–carried to completion in medieval Chaghatay and its modern descendant, Uzbek–is the result of influence from Persian.

Among the most distinguishing phonetic qualities of South Azeri–noted even among non-Turkic speakers in Iran–is a sound change whereby post-alveolar affricates /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are realized as alveolar affricates [t͡s] and [d͡z], respectively. This phenomenon is encountered in the areas around Tabriz and to the west, south and southwest of Tabriz (including Kirkuk in Iraq): čox → tsox “a lot; very” (cf. Turkish çok); čörəh → tsörəh “bread” (Turkish: çörek); Azərbaijan → azərbaidzan “Azerbaijan”; olajax → oladzax “S/he/it will be, become.”

There is a strong tendency towards palatalization of velars, /k/ and /g/ to /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/, respectively: geddax → jeddax “Let’s go” (cf. Turkish gittik lit. “we left”); xošum gəlmir → xošum jəlmir lit. “It doesn’t please me”; ikiminji → ičiminji “second (ordinal number)”; güneš kimi – jünəš čimi “like the Sun”.

Final -l is palatalized to -r in many dialects: e.g. deyir/dəyir(di) “is not” (cf. Turkish değil): yeməğimiz amade dəyir “Our food is not ready”.

There is an aversion to final -k in native vocabulary following light vowels (e/æ, ü, i) in many dialects, which has become -h, including in compounds and infinitives: e.g. ürəh (Turkish: yürek “heart”); jərəh (cf. gerek “needed, necessary”), böyüh (büyük “big”), jələjəhdə (Turkish: gelecekte “in the future”), evlənməh (evlenmek “to be married”). However, –k (and palatalization → č) is preserved in verbal constructions and loanwords: mübarək olsun deyək “let’s say congratulations.”

The -ir- indicating the continuous aspect of the verb in the 1st person conjugation is often elided to -iy- in colloquy: istiyəm ” I want” (cf. istirəm).

Another idiosyncratic feature of South Azeri is in its prosody- which generally mirrors that of vernacular Persian, but is distinguished in interrogative clauses by a flat high-tone penultimate syllable followed by an elongated, rising tone final syllable: doğrudan belə dí? “Is it really so?”

Syntax

The impact of Iranian on Azeri syntax is particularly clear in the structure of complex sentences, especially in the sociolects of the educated. Note that most of the features concerned occurred more frequently in Ottoman Turkish but have been given up in modern Standard Turkish; some subsist as substandard varieties.

In vernacular speech, particularly among the educated, imitations of Indo-European language-type subordinative constructions (from Persian) are used instead of Turkic, left-branching, constructions, in which the subordinated elements are more or less expanded sentence constituents:

| English | Turkish | Southern Azeri | Persian (transliterated) |

| “That woman for whom you bought a book” | Kitap aldığın kadın | O xanım če biləsinə kitab aldın | An zani ke barâš ketâb xaridi |

Like the Iranian subjunctive, the optative is often used as a sort of subordinative mood. It is formed by adding -a(m/n/x) to the stem of the verb, which mirrors the pattern in vernacular Persian:

| English | Turkish | Southern Azeri | Persian (transliterated) |

| “I don’t want this behavior to continue” | Ben bu davranışın devam etmesini istemiyorum | Mən istemiyəm bu rəftar ıdamə tapa | Man nemikhwâm in raftâr edâme paydâ kone |

| “S/he has no right to start talking” | kendisinin konuşmaya başlama hakkı yok | özünün haggi yoxdu bašlıya danıša | xodeš haq nadâre šoru’ kone harf bezane |

As in Ottoman Turkish and Chaghatay, Persian subordinative conjunctions, alien to Turkic sentence structure, are widely used, particularly ke (often palatalized to če), which appears as a connective device between sentences of different kinds, e.g

| English | Turkish | Southern Azeri | Literary Persian (transliterated) |

| “I want to say that this issue is not that important” | Bu meselenin o kadar önemli olmadığını söylemek istiyorum | [Istiyəm deyəm]/[deməliyəm] če bu məs’ələ o gədər önəmli deyir | Mikhwâham beguyam ke in mas’ale ânčenân mohem nīst |

| “I hope you will like it” | Umarım beğenirsiniz | Umid elirəm če xošunuz jəlsin | Omidvâram ke xošetân biyâyad |

Morphology

The Turkic noun-forming suffix –lik, -lıq is parallel to Perisan -i, -gi has been used to create from lexemes adopted from Persian: širinlik “sweetness”; həmišəlik “eternity”; əzadarlıq “misery, melancholy”. The Turkic particle –li “of, from” is used in placed of Persian constructions with bâ– or -mand “with”: ərzišli “valuable” (cf. با ارزش bâ arzeš lit. “with value”),

The formal register of Southern Azeri makes use of the comparative case form daha, while the dialects have –rax (cf. Uzbek -roq) and -tər (from Persian): daha böyük; böyühtər “bigger”; daha tsox; tsoxtär “more.” The superlative case form ən is sometimes substituted wholesale from Persian: behtərin vs. ən yaxšı “best”.

South Azeri makes extensive use of -(ıy)nan/(iy)næn “with; by” in place of Northern -(ıy)la/(iy)le: mənnən (mənimle) ; gardašlarıynan (qardašlarla) “with friends”, birbiriynən (bi-biri ila) “with each other”

The Persian measure words تا- -tâ and -دانه -dâne have been assimilated into one: –dənə, e.g. iki dənə gözəl evlər “two beautiful houses” (cf. Persian: دوتا خانه زيبا do tâ xâne-ye zibâ).

Oghuz Turkic does not have an equivalent of the standalone verb “to be able to”, and instead utilizes a construction with a conjugated personal suffix from the verb -bilmek “to know”. In contrast, South Azeri vernacular uses an innovative standalone verb eliyəbilmax (cf. Turkish edebilmek “to be able to do”) followed by the optative, which mirrors the subjunctive mood of Persian. This construction has equal currency alongside the inherited Turkic construction:

| English | Turkish | Southern Azeri | Literary Persian |

| “s/he can sit” | oturabilir | eliyəbilə(r) otura | ميتواند بنشيند mitavânad benešinad |

| “I cannot be everyone’s friend” | herkesin arkadaşı olamam | eliyəbilmirəm hər kiminin dost olaram | نميتوانم دوست همه كس باشم nemitavânam duste hamekas bâšam |

| “I cannot be” | olamam | olabilmirəm; eliyəbilmirəm olaram | نميتوانم باشم nemitavânam bâšam |

Lexicon

Azeri is Oghuz in provenance and thus shares the majority of its core lexicon with other members of that clade, particularly Turkish and Turkmen. However, Azeri shares some lexical affinities with Central Asia (i.e. Uzbek) vis-à-vis Anatolian Turkish: e.g. indi “now” (cf. Uzbek: endi; Turkish şimdi); yaxšı “good” (Uzbek: yaxshi; Turkish: iyi); öz “oneself” (Uzbek: o’z; Turkish: kendi); tapmax “to find” (Uzbek: topmoq; Turkish: bulmak).

Some alternative forms are in use compared to Northern (Soviet) Azeri: e.g. eləmax for etmək “to do”.

Calques from Persian are pervasive, exceeding in number those found in Northern Azeri and Turkish: aradan getmax (from از بين رفتن az bayn raftan “to be annihilated”); xaheš elirəm (from خواهش ميكنم xwâheš mikonam “please; you’re welcome”); buyurmax in the formal meaning of “to say” (from فرمودن farmudan; e.g. o jür če buyurduz “just as you said…”); numerous izâfe constructions modeled on Persian patterns using the helping verbs vermək “to give”, eləmax “to do”, čıxmax “to go out”, vurmax “to hit”, e.g. idamə vermək “to continue”(from ادامه دادن edâme dâdan); vərziš eləmax “to exercise” (ورزش كردن varzeš kardan).

A young Circassian in Maykop, capital of the Republic of Adyghea, Russia. In recent years the republic has experienced a deepening interest in the descendants of Circassian deportees abroad, often pleading to the diaspora to repopulate their historic homeland in light of upheavals in the Near East.

A young Circassian in Maykop, capital of the Republic of Adyghea, Russia. In recent years the republic has experienced a deepening interest in the descendants of Circassian deportees abroad, often pleading to the diaspora to repopulate their historic homeland in light of upheavals in the Near East.